Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — When Utah researchers first viewed the state's soil moisture levels this spring, they could hardly believe what they saw.

"We were so far below the minimum bounds of what we've seen historically that we didn't trust the graphics when we first looked at them," said Jon Meyer, a climate scientist with Utah State University's Utah Climate Center.

The soil moisture levels Meyer and his colleagues were looking at that day were a result of Utah's drought, which is linked to an ongoing "megadrought" dating back to 2000. While the short-term effects of Utah's drought this year may have started as a result of the driest calendar year on record, experts point to that two-decade-long megadrought as a key component to dry soils and depleted lake and reservoir levels across the state and region.

The West megadrought is considered the worst long-term regional drought since at least the 1500s if not the past 1,200 years, according to a study published in the journal Science last year. However, a new NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies-led study suggests that soil moisture levels in Utah and across the Southwest will continue to dry in the next century — and at more dire rates if carbon emissions continue at the pace they are now.

The paper, published earlier this month in Advancing Earth and Space Science, suggests even "modest warming" can result in a 50% probability that a megadrought like the one the Southwest is currently in will appear again by the end of the 21st century. That means a 21-year megadrought wouldn't be a once in a 400-year or 1,200-year occurrence but potentially a twice-in-this-century phenomenon.

What's more, they found there's still a likelihood of drying conditions across the Southwest even if global temperatures don't heat up as much as feared.

"The high levels of 21-year drought risk are driven by large precipitation declines in half the models, which shift the region to a drier mean state under even the lowest warming scenario," the researchers wrote.

Looking at the effects of a megadrought

The study isn't much of a shock for researchers like Meyer, who continue to study the effects of the current megadrought firsthand.

It's not just unbelievably dry soil levels, which itself can amplify the effects of droughts; he points to the Great Salt Lake, which reached its lowest water levels on record in one of its locations this past summer, as another example of the megadrought impacts.

While it doesn't produce freshwater for human consumption, Meyer said researchers consider it to be "an excellent barometer" for the state's water resources. It's also believed to be one of the best bodies of water to help climate scientists understand Utah's water history and also forecast Utah's water future.

"Seeing it touch its record lows over the last 150 years this year is certainly cause for concern going forward — just knowing how closely tied Utah's economic prosperity is with water resources," he said.

Then there's Utah's reservoir system, which relies heavily on snow. It's estimated that upwards of 95% of the state's water comes from snow runoff in the spring. The state's reservoirs are constructed to hold that runoff and keep Utah supplied with drinking and irrigation water.

Our reservoir system has been built based on the premise of lots of spring runoff occurring and storing that spring runoff. That hydrological assumption is changing before our eyes.

–Jon Meyer, a climate scientist with Utah State University's Utah Climate Center

The Utah Climate Center has found that Utah's "snow season" has only gotten shorter since 1980, with later snowpack starts and earlier snowpack ends — generally speaking. The 2021 snowpack season, for example, peaked a little more than a week before the 1981-2010 normal, according to Natural Resources Conservation Service data.

It's not only that. Meyer said there have been more and more instances of rain events during the normal snow seasons, which he said accelerate snowmelt at times when the state needs to continue to building snowpack. Those two issues, in addition to less rain, have led to the reservoir situation.

Droughts also factor into reservoir supply beyond precipitation totals. Brad Rippey, a meteorologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, explained to KSL.com earlier this year that moisture after prolonged dryness ends up going to "replenishing" groundwater reserves before it refills reservoirs.

The Utah Department of Natural Resources reports that its reservoir system is at about 48% capacity near the tail-end of the 2021 water year.

Related:

The state's low reservoir capacity is believed to be tied to a mixture of both types of droughts. While some of Utah's smaller reservoirs can refill after just one good snowpack, larger ones like Lake Powell take much longer to refill. It fell to the lowest level since the reservoir was created this year and is now listed at 30% capacity, which is generally tied to the megadrought.

"It's really changing to a significant degree the hydrology of our region," Meyer said. "Our reservoir system has been built based on the premise of lots of spring runoff occurring and storing that spring runoff. That hydrological assumption is changing before our eyes."

Droughts of the future

The Advancing Earth and Space Science study suggests these issues will only worsen with time.

"We find that warming in the future will increase the risk of both extreme single-year and 21-year soil moisture droughts that are similar to major events of the last two decades," researchers wrote.

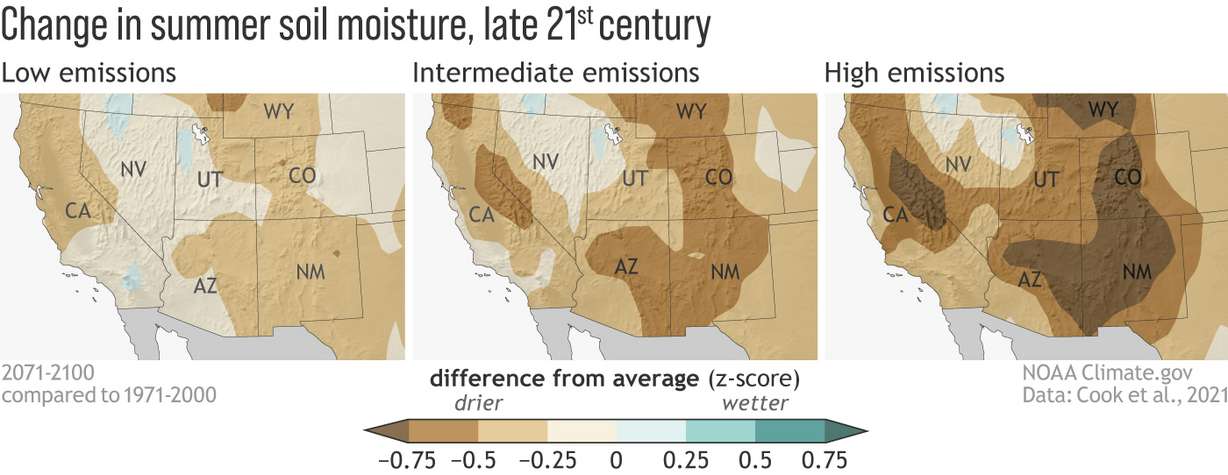

They published a graphic that shows that there is a stronger probability that soil moisture levels will be drier in the final 30 years of the 21st century than in the final 30 years of the 20th century regardless of "low," intermediate" or "high" emissions driving up global temperatures.

But the study doesn't mention that there is also a growing demand for water that is expected over the remainder of the 21st century. Utah is the fastest-growing state in the country in terms of percentage increase and its population is still on track to double over the next few decades.

The increased population and stronger shortened length between megadroughts offers a "very bleak" outlook in terms of water security, Meyer contends.

"Seeing years like this occurring already is a huge alarm that's going off across the West for water resource managers," he added. "Seeing the risks involved with these long-term multiyear significant droughts, places a huge amount of stress on our water resources. ... We've got some serious challenges to figure out how we can maintain water security year in and year out."

Saving rain for another day

Now, the outlook isn't all doom and gloom. Utah will still likely have years of above-average snowpack and precipitation. For example, federal data dating back to 1895 lists 2019 as Utah's 13th-wettest year on record even in the middle of this current megadrought. That was boosted by an above-average snow season prolific enough that some ski resorts were able to stay open until July 4.

The study also shows that reducing emissions can help lessen the impact of droughts.

"Despite the apparent insensitivity of 21-year drought risk to mitigation measures, our results still demonstrate the value of climate change mitigation for reducing future drought severity and single-year extreme drought risk in the region," the researchers wrote.

But since all signs point to good water years happening few and far between, coupled with the larger water demand associated with population increase, Meyer said the current drought, megadrought and scientific outlooks are why governments and individuals alike should look into ways to reduce carbon emissions in the future.

While governments can enact laws that can reduce emissions, individuals can make conscious decisions about how they consume energy and water. Meyer said two of the ways water can be conserved are finding ways to make irrigation more efficient and reducing ornamental lawns.

"I think it's always important for conservation efforts to apply to any year — not just the dry years," he said. "I would love for people to maintain their water conservation efforts even during wet years."