Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — The percentage of Utah inside the U.S. Drought Monitor's "exceptional" category fell for the first time in months as monsoonal rains poured over southern Utah.

While that's good news, nearly the entire state still finds itself in extreme drought status despite precipitation totals severe enough to cause flooding.

About 52% of the state remains in the Drought Monitor's "exceptional" category, according to its report Thursday. That's compared to 70% last week and 57% three months ago. A little more than 98% remains in at least "extreme" drought status — down from 99% last week — and the remaining portion of the state remains in at least a "severe" drought, according to the agency.

A sliver of San Juan County is the first portion of southern Utah to move out of the "extreme" or "exceptional" categories in months.

"Just in the last few weeks we have seen the arrival of robust monsoon-related rainfall, particularly across the southern part of the state," said Brad Rippey, a meteorologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the author of U.S. Drought Monitor's report Thursday. "That did lead to a reduction in drought intensity from an exceptional drought to an extreme drought."

This week's report also moves some of the hardest-hit areas of the state from "SL" to "L" drought types. In Drought Monitor lingo, "S" indicates short-term drought that impacts agriculture and grasslands, while "L" indicates long-term drought that impacts hydrology and ecology. "SL" indicates that the drought with both types, so moving away from that is crucial.

But while the rains provide returned streamflow in affected areas, a bit of vegetation greening and some reduction in wildfire danger, Rippey told KSL.com Thursday that plenty of precipitation — possibly years of it — is still needed to get the state out of its long-term drought.

"That does not change the fact that even those areas that saw improvement still have a very serious drought situation in the long-term and that would include groundwater reserves, where applicable, as well as continuing low reservoir levels," he said. "It's not going to be cured by a couple of weeks of heavy rain."

So what's needed to get Utah out of its drought?

How the Drought Monitor works

First, here's a short explanation of how droughts are calculated.

Believe it or not, the U.S. Drought Monitor maps are still hand-drawn, using all sorts of data — information like standardized precipitation index, percent of normal rainfall, etc. — to compare current conditions with where they should be based on records.

For areas that start to creep below average, the data is then marked with five levels of drought intensity, using a D0 to D4 scale. D0, or "abnormally dry," means short-term dryness may slow the growth of plants and crops, while D4, or "exceptional drought," means much, much worse. It can result in widespread crop losses, shortages of water in bodies of water and result in higher fire danger.

These levels are essentially kept on a probability scale, too. A D1 drought is, statistically speaking, levels like the current conditions happening every 5 to 10 years. A D4 drought means one in 50 to 100 years. Since the data doesn't really go beyond 100 years, D4 is the worst drought severity, Rippey explained.

This rain helps but we're still really far behind

Some areas in southern Utah have received several inches of rain this month — sometimes even multiple inches in a few hours. The dry soils in the region from the exceptional drought helped exasperate flash flooding. Rippey points out that if there is enough rain falling all at once, there is also higher risk that water is lost to runoff instead of seeping into the soil where it needs to go to help with the drought.

The rains the past couple of weeks can otherwise seep into the upper few inches of soil and that has benefits.

"It can certainly improve the look of the landscape," Rippey said. "You're taking away the wildfire threat. You're perhaps greening up grasses, pastures, rangelands and even the forest canopy can look better with timely rain like this."

It takes a "very robust" monsoon season to have that rainfall deeper into the ground to get several feet into the soil level.

"(The recent rain) will help, but it's unlikely to significantly change soil moisture at great depths for a long, long time," he added.

So, despite the fact there's been plenty of it the past few weeks, it's not even close to what's needed to completely fix drought issues. You can blame the West's "megadrought" for this.

It's going to take multiple years of active monsoon seasons and active winter wet seasons with mountain snowpack to fully eradicate this drought because it's lasted so long and gotten so serious.

–Brad Rippey, meteorologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture

The megadrought is the result of the greater part of the past 20 years spent in severe drought. Researchers say that it's the worst ongoing drought since at least the late 1500s if not the past 1,200 years. This is the long-term drought that remains in the U.S. Drought Monitor report in addition to the deficits still listed from the short-term drought.

"Even though, visually, the drought has improved, there are still extremely serious issues related to what has turned out to be, for a lot of the American Southwest, effectively a two-decade drought where we've seen three-quarters of the years going back to the beginning of the 21st Century that have been drought years by any definition," Rippey said. "And so that's why we still see the Great Salt Lake and even managed lakes like Lake Mead at record lows because a few days of monsoon showers are not going to replenish groundwater reserves or boost streamflow enough to help fill these large lakes in reservoirs."

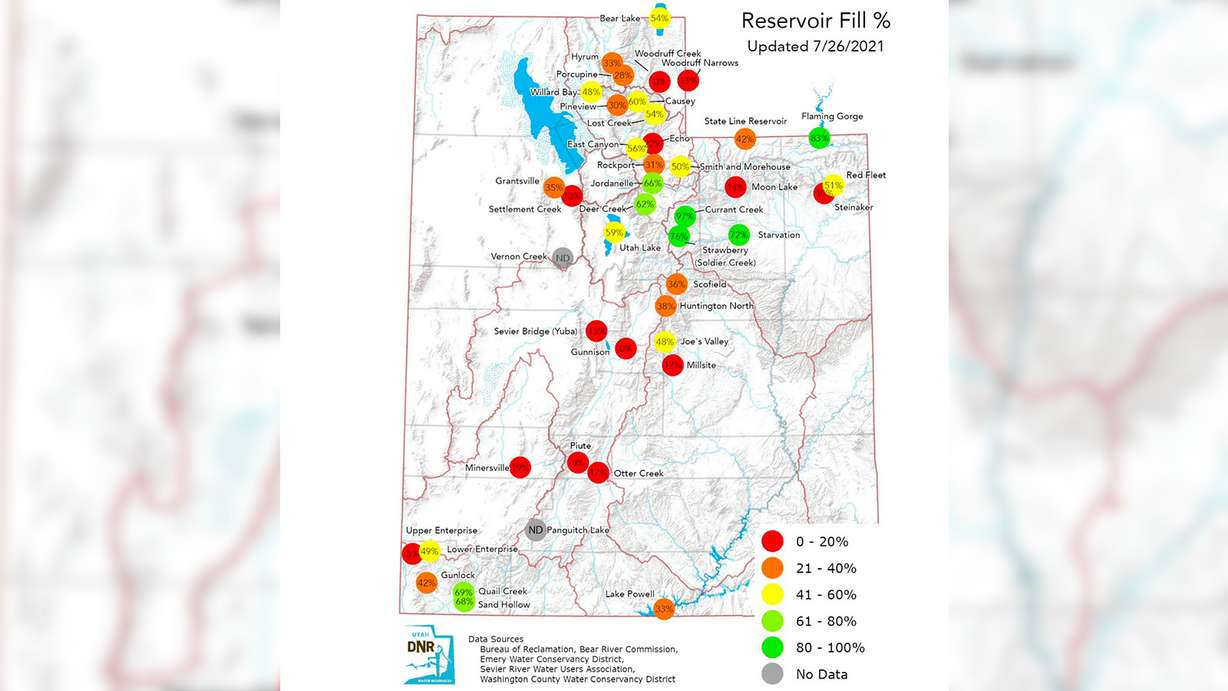

To that point, Lake Powell in southern Utah also reached an all-time low. The Utah Division of Water Resources lists it as 33% full as of Monday. The division tracks lake and reservoir capacity at 43 lakes and reservoirs across the state. Of the 41 with available data, 23 are listed at 40% capacity or below as of Monday. Another 10, including Utah Lake at 59%, are listed at between 41% and 60%. Only eight are listed at 61% or above, including Flaming Gorge at 83%.

Focusing more on the areas that have gotten rain, there are 16 tracked reservoirs from Scofield south. Only Quail Creek and Sand Hollow are above 60% capacity among the 15 with data. The rest are below 50%, including seven still below 20%.

Jordan Clayton, a hydrologist with the National Resources Conservation Services and the snow survey supervisor in Utah, told KSL-TV last week that Utah's overall capacity could drop from about 55% now to 40% by the end of the summer, and to even as low as 15% by the end of next summer based on if trends continue over the next year the way they had heading into July this year.

"It's going to be a very long process and it's going to take more than just one active monsoon (season)," Rippey explained. "It's going to take multiple years of active monsoon seasons and active winter wet seasons with mountain snowpack to fully eradicate this drought because it's lasted so long and gotten so serious."

How much rain do we need to escape the drought?

There really isn't a definite number that would take Utah out of its drought but there are some rough estimates out there.

Clayton provided Utah leaders with a report about the state's water situation earlier this month. The report calculated Utah was about 17.5 inches behind the "average precipitation" from the start of the drought — spring 2020 — to now.

"Now maybe that's exactly the right number for getting out of the drought or maybe it's not. It might be too conservative of an estimate or maybe it's too high in that sense," he said. "At least it gives us a rough idea in terms of getting out of this situation."

There's also the Palmer Severity Index, which Rippey said used to be the gold standard for drought information before the Drought Monitor emerged at the end of the 1990s. It estimates Utah's Wasatch region needs about 9 to 12 inches of precipitation to get out of a drought.

To put that into context, the National Weather Service's station in Salt Lake City has recorded just 8.4 inches since the water year began on Oct. 1, 2020. It's also close to one full year of year. The normal, based on water years from 1991 through 2020, is 15.52 inches, according to the weather service.

Regardless of any exact figure, Clayton said it's extremely unlikely that a drought deficit would be fixed by monsoonal rains alone. He points to winter snowpack, which provides the vast majority of Utah's water, as the solution. It's still unknown if the conditions will align for Utah to have a good snowpack this winter.

Even then, he, much like Rippey, believes it'll take years to close the gap.

"We could potentially get a drought-buster winter. It would be statistically unlikely. It would take a really, really extraordinarily deep snowpack to have this turn around in one winter," Clayton said. "More likely, if we're going to get out of this drought, it's going to be multiple seasons of above-average snowpack that are going to help us out in that regard."

Contributing: Jed Boal, KSL-TV