Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY -- In the debate over illegal immigration, the argument is often raised that the people who knowingly employ undocumented workers deserve much of the blame.

But there is another side to that story. Because they are in the country illegally, is it OK to cheat them, take advantage of their labor and refuse to give them pay?

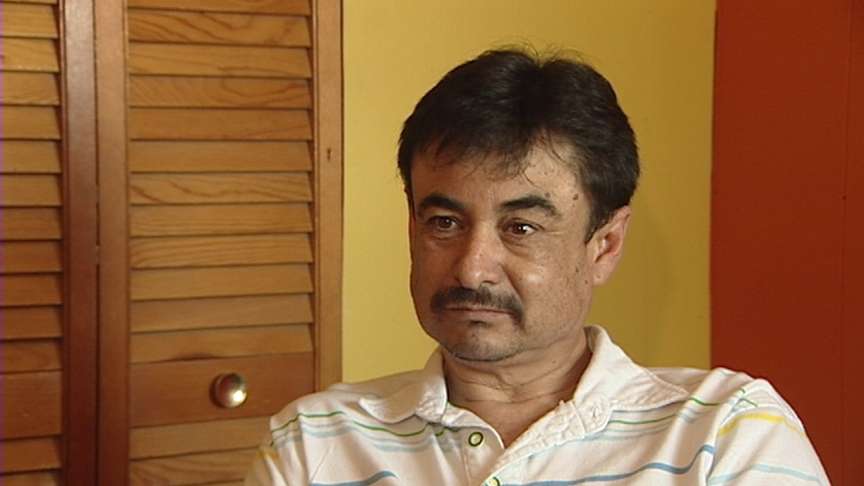

When Carlos Chavez moved to Utah more than a decade ago, he came here legally with a visitor's visa. But by the time it had expired, he had built a new life.

He decided to stay and found work in his trade as a dry-wall finisher. He answered a call for construction workers he heard in an advertisement.

"I listened to him on the radio," says Chavez through a translator. "He said he was announcing he had some work in some homes."

Chavez says the contractor agreed to pay him $5,000 for his work. But when it came time to collect his paycheck, he says the company refused to pay him.

What it does is it creates a huge underground demand for undocumented workers. If exploitation is easy, more and more employers are going to do it.

–Aaron Tarin

"After the work was finished, I had to fight for about a month and a half to just get that $1,700 from him," Chavez says.

That was about a third of what he was owed. But when he tried to collect the rest, Chavez says he was threatened.

"They say, ‘You keep asking for your money, I'm going to turn you over to immigration,'" he says.

Immigration attorney Aaron Tarin says Chavez's situation is not unusual.

"Very, very common complaint," he says. "Especially in this economy, when things are so tight, you see a lot of these abuses becoming more and more common."

Tarin says Chavez's story is all too common: undocumented workers desperate for work, employers looking for cheap labor, and the opportunity to take advantage of a population who fears deportation more than lost wages.

"I've actually had employers on the phone tell me, ‘Well, file whatever you have to have to do,'" he says. "Because they just know that most people are just too scared to come forward.

Coming forward means filing a complaint with the Utah Labor Commission. But that entails giving the state agency identifying information.

Tarin says after the release of a list of alleged illegal immigrants by rouge employees of Utah Department of Workforce Services, convincing his clients to file a complaint is a hard sell.

The desire for cheap labor is already underground in many instances. That's why there has to be penalties for businesses that knowingly hire illegal aliens.

–Rep. Stephen Sandstrom, R-Orem

"Nothing is safe. The 1,300 people that were on that list pale in comparison when you look at the DMV database for example, or the labor commission's complaint database," he says. "All of a sudden, those databases become potential huge immigration hit lists that people are going to be afraid to be on."

Tarin points to recent proposed legislation by Rep. Steven Sandstrom, R-Orem, as more reason for exploited workers like Chavez to avoid reporting the problem. The bill would give protection to state workers who report anyone they believe may be in the country illegally,

Tarin believes it offers more incentive for employers to take advantage of undocumented workers.

"What it does is it creates a huge underground demand for undocumented workers," he says. "If exploitation is easy, more and more employers are going to do it."

Sandstrom says the problem is already there and that his bill is a way to stop it. He says his legislation would only affect anyone a state worker suspects is abusing state benefits, not someone filing a complaint.

"The desire for cheap labor is already underground in many instances," Sandstrom says. "That's why there has to be penalties for businesses that knowingly hire illegal aliens, and there will be a companion bill to mine coming forward to that effect."

Utah Labor Commission officials acknowledge the problem, but say citizenship isn't something they track.

"If they employed them, hired them, suffered them to perform services that they benefited from, they should pay them their wages," says Brent Asay with the commission, "regardless of what their status is."

Chavez has again gained legal status as a resident. He is one of the few workers who did step forward to file a complaint and has now spent more on legal fees than what he was originally owed for his work.

But to him, it's no longer about the money. It's about principle.

"I think Utah is a paradise for lots of contractors because we mean nothing to them," says Chavez. "There's a lot of people who love to fraud you like this."

KSL tried to reach the company Chavez said owed him money, but was unsuccessful.

E-mail: jstagg@ksl.com