Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Lori Prichard reporting

Produced by Kelly JustSALT LAKE CITY -- It's no secret we are in a recession. State budgets are being slashed. Cities and counties are looking for ways to cut back, but in a KSL 5 News investigation we found there is a small sliver of the government workforce that doesn't seem to have been affected by the downturn in the economy. In fact, these workers are essentially getting two paychecks for working one job.

How do they do it? It's called "retiring in place" or "post-retirement employment." Either way you put it, it is perfectly legal. Utah law says only the state's police chiefs and sheriffs, along with the head of the Department of Public Safety, are allowed to remain on the job with no break in service after retirement.

Last year alone, the state retirement fund--called Utah Retirement Systems, or URS--lost $4 billion. Currently, lawmakers are wrestling with how to recoup that shortfall so it doesn't endanger the viability of the state's retirement fund. However, when KSL began asking about post-retirement issues, such as "who is retiring and coming back to work?" no one could really answer those questions.

No state agency tracks that information. When a government employee retires and starts collecting pension, he or she is dropped from the URS system. So, as URS Executive Director Robert Newman explained, "We don't maintain a database of those people because they aren't participants in URS."

If KSL wanted to know who was retired in place, we found we would have to take on the task of compiling the numbers.

KSL collects the records

Beginning in August, KSL sent out more than 200 records requests to every law enforcement agency listed with the Utah Chiefs of Police Association and the Utah Sheriffs' Association asking for salary and retirement data.

Once that information began coming in, we built a database to track who answered the Government Records Access Management Act, or GRAMA, requests and who had not. We also built a second database specifically for the police chiefs and sheriffs who had retired in place.

The numbers we complied show more than one out of three law enforcement agencies has a chief or sheriff who is retired in place. [CLICK HERE for a list of those sheriffs and police chiefs retired in place]

Of those who are retired in place, we estimate the majority make well over $100,000 in post-retirement benefits; some make more than $200,000.

Retiring in place

So how does retiring in place work? Bountiful City Manager Tom Hardy, a vocal opponent of retiring in place, sits on the Utah Retirement Systems Membership Council and studies retirement issues as a member of the Utah League of Cities and Towns. He described the retiring-in-place policy as "collecting 60 or 70 percent of your salary in a retirement benefit and getting 100 percent additional salary, plus a 401(k)."

"If they retired after 25 years of service, making $125,000, they'd get half of that, or $62,000, which would be total of $180,000. Plus, they'd be getting between 25 percent to 35 percent to 40 percent in a 401(k). Well, that's another $30,000 to $35,000. They're making well over $200,000," Hardy explained.

URS pay formulas

Let us break it down. URS rules allow law enforcement officers to retire after 20 years. The actual URS formulas are as follows:

- 2.5 percent x Final Average Salary (FAS) x years of service up to 20 years

- 2.0 percent x Final Average Salary (FAS) x years of service over 20 years

Essentially, after 20 years of service, a peace officer can retire at half of his or her Final Average Salary (FAS). The FAS represents the highest three years of earnings converted to a monthly average.

After 25 years of service, that percentage climbs to 60 percent of FAS. After 30 years, it's 70 percent of FAS. However, the percentage cannot go higher than 70 percent.

So, let us use Pleasant Grove's police chief, Thomas Paul, as an example. According to information provided to us by Pleasant Grove, Paul retired on June 30, 2002. He had been employed with Pleasant Grove's police department since April 1975. (Police chiefs do not need to be in place 20 years to retire. They just need 20 years or more of service credit working as a law enforcement officer.)

According to the city, Paul has been in law enforcement for 27 years prior to retirement, so his pension would be 64 percent of his final average salary, according to the URS pension formula.

Take that percentage and add how much he earns working as police chief in Pleasant Grove, which is $103,254 according to the city. Then add $24,719 that the city tells us they pay into his 401(k). Those numbers come to roughly $171,000.

KSL was not able to obtain the exact amount of each individual's pension. That information is not considered open record under the state's GRAMA laws. However, we were able to obtain salary data prior to each person's retirement, which gives us an estimate of each individual's FAS.

"The term 'retiring in place' is an oxymoron. They're not retiring in place. They're just staying in place. They're not retiring at all," Hardy argues. "All they're doing is getting a check, another check and, actually, a third check with the 401(k)."

Unique 401(k) accounts

And let's examine those 401(k) accounts cities and counties can choose to fund. The contribution rates being put into these retirement funds are unheard of in the private sector:

- 31 percent in Ogden

- 26.25 percent in Salem City

- 26.20 percent in Woods Cross

- 25.90 percent in South Ogden

- 25.40 percent in Harrisville

- 23.34 percent in Clearfield

- 22.61 percent in South Jordan.

These percentages are entirely funded by taxpayers, according to the information we obtained from cities and counties.

As URS Executive Director Robert Newman explained, these percentages and others are set by their actuary and ratified by the state retirement board.

These are the percentages that are paid into the state retirement fund by cities and counties on behalf of the majority of public safety employees. Yet, if an employee has retired from URS, rather than paying that money into the state retirement fund, URS gives the option of allowing cities and counties to negotiate with a police chief or sheriff for an additional 401(k) and/or other defined benefit plan.

Our investigation did find cases where some cities and counties chose not to offer a 401(k), the city of Kanab being one example. However, we also found confusion on the part of some cities who, according to them, where under the impression they must fund 401(k) accounts.

For example, Police Chief Val Shupe told us he negotiated a lower contribution rate with South Ogden when he retired in place. However, he told us South Ogden received a letter from URS stating the municipality must pay the full contribution rate, which is currently 25.90 percent.

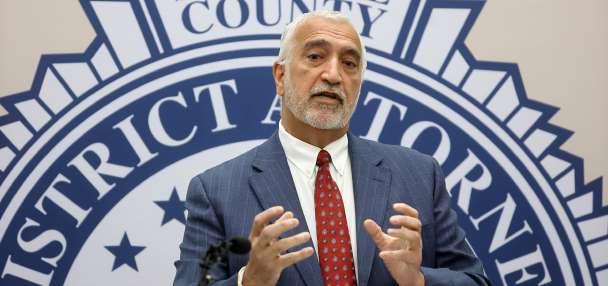

Ogden Police Chief Jon Greiner recounted a similar story.

"[The] retirement system sent a nasty letter to [South Ogden's] city manager and said, ‘no you will pay him the full rate.' Even though he had his full 30 years in, he should have been free to negotiate because he's an appointed official. [He] should have been able to renegotiate that. URS said, ‘no,'" Greiner said.

Greiner said he too negotiated a lower rate, lower than the 31 percent he said he receives. But, he told us Ogden raised it to comply with what they thought were mandated URS rates.

Support for retiring in place

"It's allowing our homegrown people to compete with everybody else who's in a national marketplace who may be competing for the job," Greiner said, while defending the retire-in-place policy.

Back in 2002, Greiner lobbied the state legislature to pass House Bill 230, which opened the door for police chiefs to retire in place. By statute, sheriffs were already allowed to do it.

Now also a state senator, Greiner sits on the legislative committee that oversees state retirement issues. Greiner argued by allowing a retire-in-place policy it gives Utah law enforcement officers who are vying for a top job in the state a leg up to those applicants from out of state who might have a law enforcement or military pension. Greiner also said retiring in place offers an incentive to allow police chiefs and sheriffs to remain at their job.

"As I was getting close to 30 years, I was looking for opportunities to go and do something else, because that's the way the system is set up. There was no incentive to stay here past 30 years. You've reached your cap at 30 years at 70 percent," said Greiner.

By letting him retire in place, which he did back in 2002, Greiner also added Ogden doesn't have to "spend six months to nine months in training costs to get up to speed."

Our investigation found Chief Greiner's post-retirement package, including pension estimates, current salary and 401(k) contributions made by Ogden, is roughly $195,000.

Only two other police chiefs make more. Just ahead of Greiner is Murray Police Chief Peter Fondaco. His post-retirement package is an estimated $200,000. But the top retired-in-place earner is Provo's Police Chief Craig Geslison. We estimate he makes around $210,000.

When KSL raised the question of how much the retire-in-place policy is costing, Greiner said, "I don't think there's a huge cost in this."

2006 URS audit

However, a legislative audit on post-retirement re-employment disagreed with that assessment. The December 2006 report concluded the practice "provides a financial incentive to employees to retire as soon as possible so they both receive payment and be re-employed, in their pre-retirement position and in their department."

It went on to cite URS's actuary, who said the system is "susceptible to abuse."

This report, did not examine the retiring in place being done by Utah police chiefs and sheriffs. Instead, it concentrated on other state workers who are allowed, by law, to return to work post-retirement once they've met certain guidelines.

The audit suggested specific changes to the retirement system to curtail the number of retired employees who go back to work. However in 2006, lawmakers did not follow those recommendations.

Today, lawmakers and others close to the issue tell KSL something needs to change to help shore up the $4 billion URS lost last year. But right now, there is little agreement on what exactly those changes should be.

If you would like to follow the post-retirement debate, there is a legislative hearing that is scheduled for November 12 at the Capitol.

Also, a 2009 legislative report titled, "A Performance Audit of the Cost of Benefits for Reemployed Retirees and Part-Time Employees" is expected to be released by the committee.

You can also listen to recent committee hearings by clicking HERE.

E-mail: iteam@ksl.com