Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

LOGAN — Utah's rollercoaster water year hit another bump in January.

In Salt Lake City's case, the 0.47 inches of precipitation recorded in January was 0.96 inches below the 30-year normal for the city. This January just missed landing in the top 10 driest Januarys since the National Weather Service began tracking Salt Lake City weather data in 1874.

While the statewide numbers will likely be released next week, the slowdown in Utah's capital can be found in the statewide snowpack data, too. The statewide snowpack level has only gained 0.1 inches of precipitation since Jan. 9, and enters February at 9.1 inches of water, according to Natural Resources Conservation Service data. The good news there is that so much was accumulated in December and early January, that it's still at 100% of normal for the first day of February.

Most of the snow produced Wednesday morning — about 3 inches in places like Magna, compared to 1 inch in Alta — was the result of winds off the Great Salt Lake producing lake-effect snow, per the National Weather Service.

So what's causing this recent slowdown in precipitation over the past few decades that's drying up the West?

It's easy to point to persistent and stronger high-pressure ridges. High-pressure ridges are associated with hotter and dryer temperatures in the summer, and the lack of snowstorms during the winter, because the patterns essentially block clouds and storms from entering the area. Inversions also pop up when there's a high-pressure ridge in place, leading to the smoggy air along the Wasatch Front.

These are the types of patterns that emerged over the past couple of weeks, resulting in the drier-than-average month and poor air quality events.

It's also what Wei Zhang, an assistant professor in Utah State University's Department of Plants, Soils and Climate, expected to find when he first began sifting through all sorts of weather data from 1980 to 2018.

"The drying trend should be tied to this strengthening of ridge patterns," he said, reflecting on his beliefs heading into the study. "There have been a lot of papers that discussed the ridge patterns ... that can be used to explain some of the drought conditions in California or some other states in the Western U.S. So, your first (thought) could be 'there should be some increase in trend in that ridge.'"

But that's not what he found as combed through all sorts of weather datasets from the past four decades. And a new study published last week in the Geophysical Research Letters, led by Zhang, now challenges the notion. The study found that the frequency of high-pressure events in the West didn't really change between 1980 and 2018.

Instead, over that same time span, researchers found there was a decrease in troughs, which are low-pressure systems associated with wetter-than-average and colder-than-average temperatures. Simply put, there was a decreasing number of storms in the West over the past four decades to push out high-pressure ridges, and that led to the emergence of drier conditions, including the region's current megadrought.

To get these results, Zhang and a team of USU researchers went through different weather and climate datasets, records kept by agencies like the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and NASA. Vittal Hari, a researcher at the Helmholtz-Centre for Environmental Research, helped produce data in the study tied to European drought events.

They then created five weather categories, such as troughs and high-pressure ridges. As they put the data together, they found the only real trend was a gradual decrease in the number of troughs. It appears this was missed in the past because researchers were focusing on high-pressure ridges and not really paying attention to trough data.

All this is not to say high-pressure ridges haven't factored into drying conditions over the past few decades. Large high-pressure ridge patterns in California around 2016 resulted in significantly dry conditions at the time. It also doesn't mean there aren't any more troughs, because Utah's snowy December is proof those can still form.

"But when you put that back in the longer background and you look at the frequency of the regional patterns, we didn't see that increase of trend in the frequency or the number of days in the ridge patterns," Zhang explained. "We had to look at this from a different angle. And we found that the decrease in precipitation in the West can be mainly explained by that decrease in the frequency of the trough patterns."

What's making this happen?

With the results in hand, the team of researchers then started work on an attribution analysis of the data. They wanted to find what was behind this trend. Data overlaps pointed to the increase of greenhouse gases emitted into the atmosphere from human activity as a major factor in the storm decrease, Zhang added.

What's interesting about the results of the study isn't that it's exactly the opposite of what he expected heading into it, it's that greenhouse gases are producing a completely different effect elsewhere in the country.

Zhang, then at the University of Iowa, co-authored a study published last year in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences that found greenhouse gas increases are behind more precipitation and flooding in the Midwest. He used many of the same tactics from that study to look at the West more in-depth.

If there were no actions taken to reduce the carbon emissions, I think this drying future in the Western U.S., including Utah, I think that could be the future that we will see — at least, based on the modeling results.

– Wei Zhang, Utah State University Department of Plants, Soils and Climate

The difference in weather and climate events in the West has also resulted in completely different outcomes. While the Midwest deals with increased flooding, the West has suffered from drying bodies of water and more wildfires.

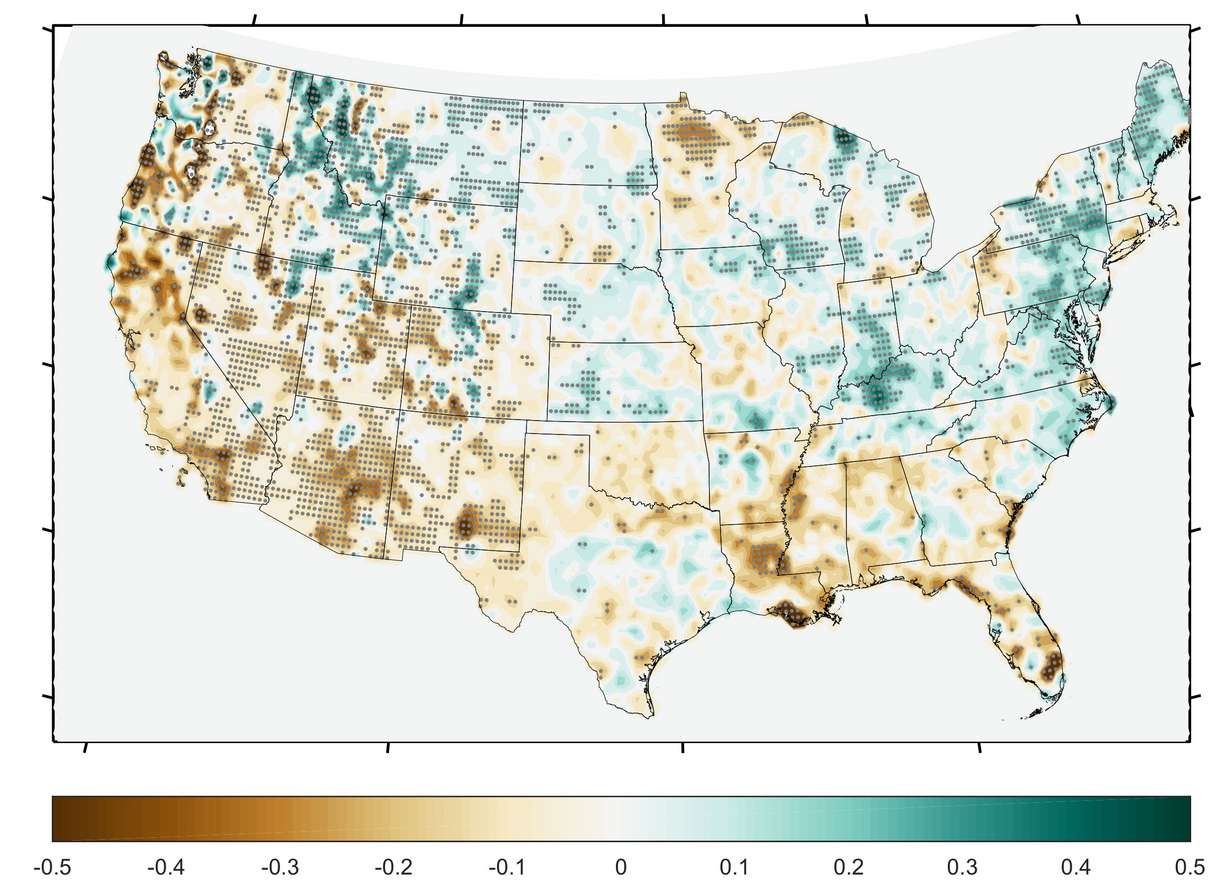

A map published in the most recent study shows storm and precipitation patterns from 1980 to 2018. Aside from some parts of northern Utah, most of Utah — especially its snowpack basins — has decreased in both the number of storms and precipitation over time. This is generally true for most of the West, especially the Southwest U.S., northern California and western Oregon. Those are regions hardest hit by drought and wildfires in recent years.

Zhang said these trends generally continued in the years beyond what the team studied. A report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Center for Environmental Information released last month found that the West's drought and Western wildfires each resulted in over $1 billion in economic losses.

The Midwest, especially Indiana and Kentucky, have seen large increases in storms and precipitation over that time. Zhang, who said he would deal with all types of flooding every year during his time in Iowa, calls this trend the "Midwestern water hose."

This map also shows general increases in the Northeast and general decreases in most of the Southeast U.S. from 1980 to 2018.

Future work

Zhang's work is ongoing. He said he'd like to use more model simulations to find the effects between rising global temperatures and trough patterns. He'd also like to see if he can find an exact reason as to why trough patterns decrease in the West as greenhouse gas emissions increase.

He and other USU researchers, including faculty within the Utah Climate Center and the new Janet Quinney Lawson Institute of Land, Water and Air at Utah State University, are looking into many different aspects of climate, especially Utah's ongoing drought conditions. It's an important issue because a NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies-led study published last year suggests megadroughts may be more common in Utah's future.

"If there were no actions taken to reduce the carbon emissions, I think this drying future in the Western U.S., including Utah, I think that could be the future that we will see — at least, based on the modeling results," Zhang said. "So I'd say we need to take some actions to that."

In a statement issued through USU, Hari added he believes the new study may also be helpful in future work that can help determine causes and even predict drying trends in other regions across the world, as well.

"The process of sorting decades of short-term conditions into weather types and then looking for trends in those conditions is a good model for exploration of changes to climates around the world," his statement reads, "and gives us another signal to look for when interpreting models of a warming climate."