Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — University of Utah researchers say an unusual sequence of earthquakes that happened in central Utah in 2018 and 2019 are a reminder of Utah's old volcanoes in the area are active. Luckily, they say there's no indication of an imminent eruption.

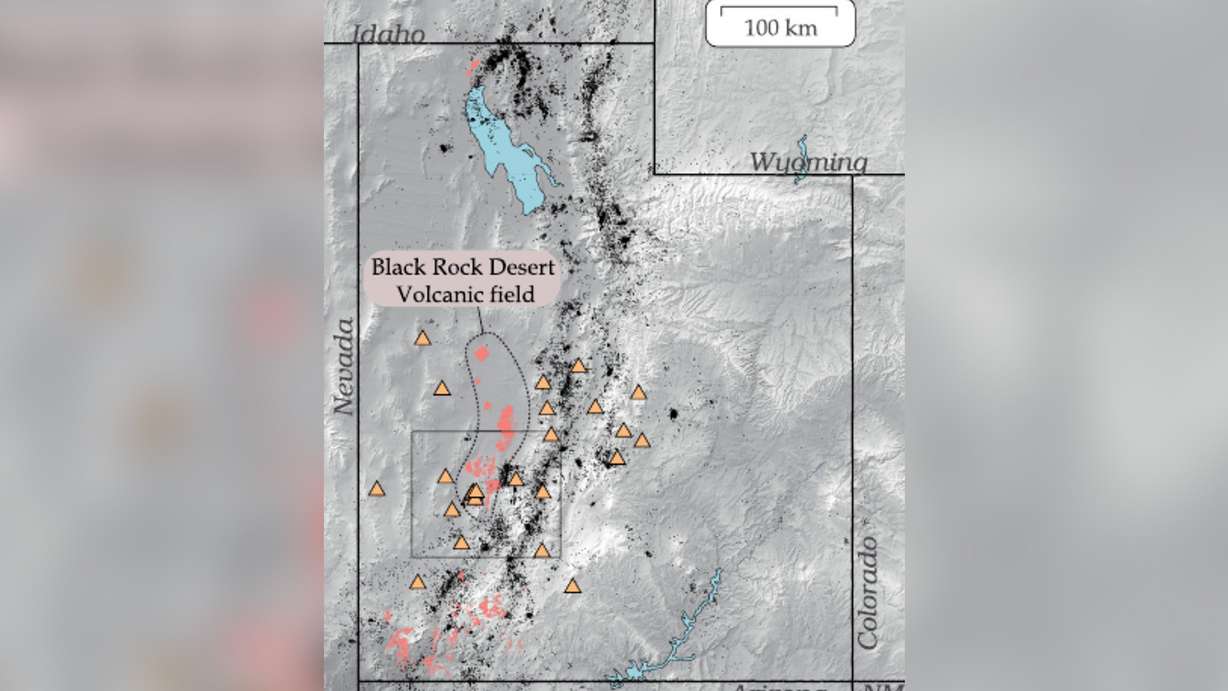

The research, which was first published in Geophysical Research Letters last month, centered around a pair of peculiar earthquake sequences in the Black Rock Desert near Fillmore. One of the central Utah earthquakes happened on Sept. 12, 2018, and the other happened on April 14, 2019. The quakes registered as 4.0 and 4.1 in magnitude, respectively, and produced several aftershocks.

The location of both earthquakes was the Black Rock Desert volcanic field that's located in central Utah between I-15 and the Utah-Nevada state line. The volcanic area last erupted approximately 720 years ago, resulting in basalt cinder cones and flows by Ice Springs, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

In addition to the earthquakes being detected by the Utah Regional Seismic Network, they were captured by temporary seismic equipment that was being used less than 20 miles from the desert to monitor a geothermal well for a different project.

A team of researchers from the University of Utah, USGS and the University of Iowa went to work analyzing the data. The temporary equipment helped detect 35 aftershocks after the 2019 quake, which was nearly double what the normal system detected.

They found that the earthquake was 1½ miles below the surface, which is pretty shallow for earthquakes. For example, the 5.7 magnitude earthquake that rattled the Wasatch Front last year happened about 6 miles below the earth's surface; the 2018 and 2019 central Utah earthquakes were unrelated to the Magna earthquake, Utah's largest since 1992.

In addition, the earthquakes didn't produce "shear waves," which are common for earthquakes in Utah. The frequency of the seismic energy was also much lower than the typical Utah earthquakes, Maria Mesimeri, a postdoctoral research associate for University of Utah Seismograph Stations and the study's lead author, said in a news release Tuesday.

"Because these earthquakes were so shallow, we could measure surface deformation (due to the quakes) using satellites, which is very unusual for earthquakes this small," she said.

The data led researchers to believe that the earthquakes weren't caused by colliding faults like most Utah earthquakes; rather, they said their research indicated these quakes were the result of ongoing activity in the volcanic field underneath the desert.

Mesimeri said it's likely both earthquakes may have been caused by either magma or heated water that made its way closer to the surface and caused the earthquakes.

"Our findings suggest that the system is still active and that the earthquakes were probably the result of fluid-related movement in the general area," she said. "The earthquakes could be the result of the fluid squeezing through rock or the result of deformation from fluid movement that stressed the surface faults."

The good news, she added, is there is no reason to believe the recent earthquakes are warning signs of an imminent eruption. It just means it's a location that researchers may want to pay attention to more intently.