Estimated read time: 10-11 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.

SALT LAKE CITY — It's expected that the first rounds of COVID-19 vaccine doses will arrive at Utah hospitals on Monday after federal regulators on Friday approved emergency use of the first of two vaccines ready to be distributed.

The Food and Drug Administration panel's decision comes after Great Britain already began its vaccination process. Hundreds of thousands of Pfizer vaccine doses are expected to be administered to frontline health care workers first before going toward long-term care facility patients and K-12 educators in the first weeks after it arrives in Utah.

Health experts say this new development isn't the end of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it offers the possibility that the end is in sight. It's also something that could set this pandemic apart from one a century ago.

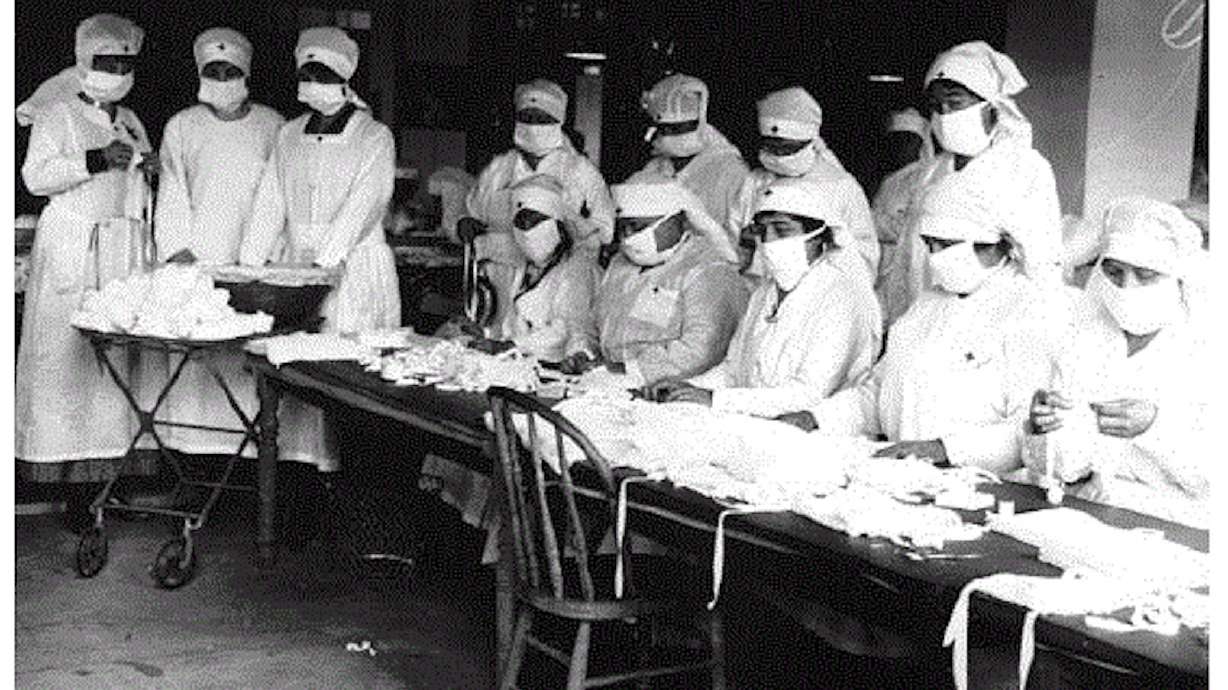

There are many parallels between the 1918 influenza and the COVID-19 pandemic that KSL.com has reviewed over the past few months for this Historic section. They include closing down businesses to curb rising cases, encouraging face coverings, and, yes, even wacky college football scheduling.

Aside from the number of deaths and age demographic in 1918 and 1919, a viable vaccine has a shot to be the stark difference between the two. Modern flu vaccines weren't developed and made available until the 1940s, as noted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, buried in Utah newspaper coverage from 1918 is a detail that never got much traction in the retelling of the worst pandemic in world history. There was an effort for a flu vaccine and reports show it was used in Utah.

So, what went wrong in those efforts?

Optimism for a vaccine a century ago

The infamous second wave of the influenza pandemic arrived in Utah by the end of September and early part of October 1918. Newspapers began to report about a vaccine being developed at Tufts University in Boston while theaters and other public gathering locations in New England were closing as a result of the outbreak.

"Much interest was manifested in experiments being made with a new influenza vaccine produced at the Tufts college laboratories," the Ogden Daily Standard reported on Sept. 26, 1918. "A fund of $100,000 provided by the executive council was made available today for the work of the emergency public health committee."

An article printed in the Salt Lake Herald-Republican three days later stated that the U.S. Congress approved $1 million toward expanding a pneumonia vaccine, which was to be used in flu cases.

Reports about a "Park vaccine," "Leary vaccine" and a "Rosenau vaccine" showed up about two months later. Newspaper articles from the time indicate that the state health department had purchased at least two of these vaccine types.

It also appears Utahns were optimistic about the vaccines as influenza tore through local and national communities. One report even touted it as a cure in another Ogden Daily Standard report.

"A vaccine, which may prove to be the absolute sure and preventative for the influenza and the superinduced pneumonia is now under the investigation by Dr. (Theodore) Beatty of the state board of health as well as the city health authorities of Ogden," the newspaper reported on Nov. 25, 1918. "The cure, which is known as the Leary vaccine, has been used extensively by a well-known Ogden physician and, according to his reports, has lowered the death rate from his disease to a very great degree."

A batch of the Rosenau vaccine arrived in Ogden in December, the Salt Lake Tribune reported on Dec. 13, 1918. It was endorsed by Beatty and given to the public for free.

As we know from hindsight, this vaccine didn't offer an end. That pandemic came to a close midway through 1919 when herd immunity was reached, as History.com pointed out. By that time, nearly everyone on the planet had either fought it off or died.

Yet the stories of these vaccines are interesting, to say the least. John Eyler, a former professor of history at the University of Minnesota, wrote in great detail the chaotic medical history of the 1918 medical research efforts in a 2010 research paper published in the American Journal of Public Health.

In his research, Eyler pointed out that there were actually several vaccines developed and used during the pandemic. They included one developed by a researcher named William Park of the New York health department, another by Timothy Leary at Tufts University, and a treatment by a researcher named Milton Rosenau, who had conducted experiments at quarantine stations in Boston and San Francisco.

The flaws of the 1918 vaccine attempts

The first problem researchers racing to find a vaccine ran into is they still hadn't figured out was influenza was. Most of the flu research at that time came as a result of another bad global influenza pandemic that ended in 1890. That outbreak resulted in the deaths of 13,000 Americans and an estimated 1 million people globally.

Eyler wrote that studies following that pandemic pointed to influenza as a result of a bacteria referred to as Pfeiffer's bacillus after the researcher Richard Pfeiffer. Despite some skepticism that existed at the time, this theory primarily continued into 1918. In fact, the CDC credits a few studies in the 1930s for first proving that influenza is actually a virus.

That's not to say they were far off on everything. Studies of the 1890 pandemic also concluded that influenza was a communicable disease and that it spread more rapidly than any other documented communicable disease to that point, the research paper pointed out.

It's possible this is why certain public health measures were in place by 1918. Other outbreaks between 1890 and 1918 led to new public health practices, as well. By the time of the flu pandemic, there was research available about the powerful influence of facial masks during the 1910-1911 Manchurian plague outbreak in China for instance.

The second problem Eyler mentions is that medical literature was "full of contradictory claims" about how successful any of the flu vaccines. That's because there didn't appear to be a set of criteria to judge the results of scientific studies even though clinical trials did exist well beforehand. In short, there weren't really any rigid or reliable standards in place to prove any claims made about the vaccines.

So when the demand for a vaccine amid the 1918 pandemic came around, the various vaccines and treatments didn't quite address the root cause for the spread, or its successes were blown out of proportion by promoters.

"The medical profession had at the time no consensus on what constituted a valid vaccine trial, and it could not determine whether these vaccines did any good at all," Eyler wrote. "The lack of agreed-upon standards was exacerbated by the informal editorial procedures and the absence of peer review in scientific publication in 1918."

Related:

Park's treatment was one that came from separating Pfeiffer's bacillus from influenza cases. The Leary vaccine worked in a similar fashion.

"His was developed from three locally isolated strains, and it was heat-killed and chemically treated," Eyler wrote. "Leary promoted his vaccine as both a preventive and a treatment for influenza."

This is the one a Utah physician eventually touted in the Ogden Daily Standard in late November 1918. An Ogden physician claimed that after 400 injections, "the majority of his patients had already reached the lowest stages of disease" and that people had "slight attacks" and not severe illness.

There isn't as much detail of Rosenau's vaccine. A collection of his work points to a smallpox vaccine he helped develop in 1907. What is known is that Ogden health leaders voted against using a Rosenau vaccine in late October 1918, per an Ogden Daily Standard report at the time. But in December, it appears to have arrived in Utah and was distributed to anyone who wanted it. Through reports from different papers, it wasn't clear if it was delivered in Salt Lake City or Ogden.

However, Rosenau's most important pandemic work came through studies that helped dispel original theories about influenza.

Creating a paradigm shift

Rosenau conducted studies at quarantine stations at a Boston harbor, and also Angel Island in San Francisco, Eyler explained. Volunteers received various strains of Pfeiffer's bacillus, which didn't do anything. He then injected the blood of influenza patients into some of the volunteers and even had volunteers interact with influenza patients, but still nothing happened.

It sparked the idea that researchers needed to go back and rework theories on how influenza spread.

"We entered the outbreak with a notion that we knew the cause of the disease and were quite sure we knew how it was transmitted from person to person," Rosenau wrote at the end of the study, which was published in 1919. "Perhaps, if we have learned anything it is that we are not quite sure what we know about the disease."

Other researchers also came to this conclusion, according to Eyler. They figured out that Pfeiffer's bacillus was just a secondary invader. It would take years after the pandemic before it was proven to be a virus and before vaccines were adjusted to that.

A different story a century later

Once again, a brand-new vaccine has emerged during a pandemic. This time it's one backed with more rigorous, uniform standards, FDA officials said. And it helps that experts were able to identify that it was a coronavirus rather quickly.

Most of the processes for drug trials like randomness and regulatory standards were formed in the time after the 1918 pandemic, Dr. Arun Bhatt wrote in a 2010 research paper on clinical trial history for Perspectives in Clinical Research. That's on top of all the other medical and technological advancements over the past 100 years.

Reports from trial studies of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines indicate about 95% efficacy. Rich Lakin, immunization program manager for the Utah Department of Health, explained last month that it was "good news" as it shows a good immune response to the vaccine.

In speaking about the forthcoming vaccine, Gov.-elect Spencer Cox said Thursday that Utahns should be excited about the advancement and use it as motivation to follow public health guidelines to avoid outbreaks between now and the time herd immunity is reached when enough people get the vaccine.

It's possibly the light at the end of the tunnel that just never quite happened a century ago.

"This really is the miracle we've all been praying for and hoping for, and to be able to have these vaccines delivered in record time is a testament to technological advancements," Cox said. "It's a testament to the tenacity of researchers and scientists who have been working around the clock to make this happen."