Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

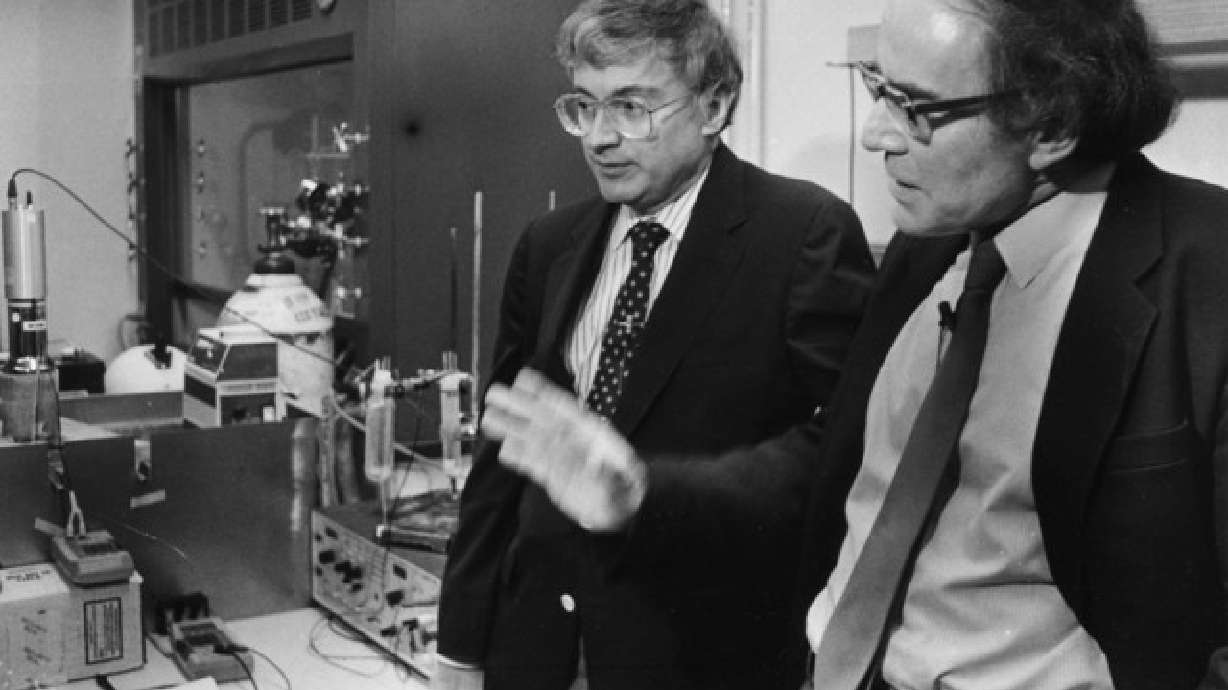

SALT LAKE CITY — Dr. Martin Fleischmann, one-half of an electrochemist duo that ignited the scientific world with claims of discovering cold fusion, has died at age 85 at his home in Salisbury, England.

Several energy publications as well as Forbes are reporting the Aug. 3 death of the world-renowned scientist, who with the University of Utah's Dr. Stanley Pons sparked an international, intellectual uproar among researchers with their tabletop cold fusion experiment.

The announcement in March of 1989 of the experiment's results turned the world's collective scientific eye on Utah, as researchers rushed to duplicate its breakthrough results, including researchers at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, which did much of the groundwork on the atom bomb.

Failure to replicate the pair's lab experiment — which they said had produced a nuclear fusion reaction at room temperature and could be the boon for the production of clean energy — led to their ostracization in the conventional scientific community and gave Utah a wounding black eye.

People will say cold fusion has never been replicated, but there's been 17,000 replications worldwide since Pons and Fleischmann,

–Sterling Allan, CEO, Pure Energy News

At the time, however, the "discovery" of cold fusion was landmark, a never-before-achieved scientific achievement that touched off a clamor because of the wide- reaching implications.

Until their announcement, scientists assumed that fusion of hydrogen atoms, which power the sun, stars and hydrogen bombs, occurs only in extremely high temperatures and pressure. The two said in their experiment, the release of thermal energy occurred under conditions at room temperature, giving rise to the possibility of energy absent fossil fuels and without nuclear power, which leaves radioactive waste.

In the aftermath, however, other researchers who failed to duplicate the results attacked the two men as frauds, accusing them of sloppy, incomplete and unethical work.

Within several years, Fleischmann and Pons were in France, quietly continuing their research through contracts with a subsidiary of Toyota. Japan committed to spend more than $20 million on cold fusion research and while traditional scientists remained hostile to the theory, research continued on multiple fronts.

Japan pulled the plug on the duo's research in 1997. By a year later, the University of Utah announced it would no longer pursue research patents.

In a 2009 interview with "60 Minutes," Fleischmann said he regretted calling the nuclear effect "cold fusion" — a name coined by a competitor — and should have resisted making the announcement at a press conference, departing from the tradition of sharing the research first in scientific journals.

The cold-fusion debacle was costly for Utah's reputation and wallet.

Utah lawmakers convened a special session and sunk $5 million into cold fusion and the National Cold Fusion Institute was established, only to see its first director resign from its board of trustees after a financial scandal erupted. In 1993, the University of Utah went onto secure the patents to cold fusion, spending more than $1 million in attorney fees and licensing those patents to a private energy company. The private company later abandoned its efforts, citing prohibitive research costs.

Related:

Dr. Chase N. Peterson, the U.'s then-president and an early booster of cold fusion, resigned amid the scientific and financial furor.

In the years since, however, researchers dedicated to the science have continued the work of cold fusion experiments.

Ephraim resident Sterling Allan is the chief executive officer of Pure Energy News, which extensively tracks research and corporate advances in the field.

He said there has been an uptick in activity, and despite the naysayers who would still discredit Fleischmann today, cold fusion is continuing to capture attention in both the business and energy fields.

Several companies are pioneering technology in what is now called the low-energy nuclear reaction movement and a high school science class in Rome built, tested and patented a device similar to what Fleischmann and Pons used in 1989.

"People will say cold fusion has never been replicated, but there's been 17,000 replications worldwide since Pons and Fleischmann," he said.

The Rome high schoolers have called their device the Athanor LENR Reactor, which is reported to be an electrolytic cell that produces a coefficient power of 400 percent.

"You commit academic suicide if you use the words 'cold fusion,'" Allan said.

Fleischmann, London-educated and one of that country's most distinguished scholars, died Friday after battling diabetes and Parkinson's disease.

Email:aodonoghue@ksl.com