Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is published through the Colorado River Collaborative, a solutions journalism initiative supported by the Janet Quinney Lawson Institute for Land, Water, and Air at Utah State University.

MOAB — Utah and the six other Colorado River basin states met virtually toward the end of April to address their differing opinions on how Lake Powell and Lake Mead should be managed in the long term and those discussions are expected to pick up steam this month.

The states are dealing with the Colorado River Post 2026 Operations Plan, which is mostly an update to an agreement the Colorado River basin states approved in 2007 to manage Lake Powell and Lake Mead — the nation's two largest reservoirs — as a part of the distribution of the river's water. It will be the latest agreement since the original distribution plan was settled in 1922.

Additional in-person meetings are scheduled for this month, according to Gene Shawcroft, chairman of the Colorado River Authority of Utah. He said discussions have been "cordial" to this point, but the upper Colorado River basin states — Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming — and the Lower Basin states — Arizona, California and Nevada — haven't budged from the different recommended plans they submitted to the federal government earlier this year.

Experts agree that Lake Powell, at 33% capacity, and Lake Mead, at 36% capacity, are in a better position now than at this time last year, but both have a long way toward full recovery.

What helps, though, is the states do agree on many of the challenges facing the Colorado River, right now, which led to this situation. Colorado River water users appear to understand that both reservoirs dropped significantly because of drought and overconsumption and the way both were managed played into that.

The discussions of how the river is managed have changed, as the entities accept the river's management should be based on supply instead of the old way of managing it by demand.

"I think there's a lot things that are common in the proposals," Shawcroft said, standing by the banks of the Colorado River. "There's no doubt that we feel pressure to do something sooner rather than later, but — at least in my mind — we don't have an imposed deadline."

How we got here

Understanding the two sides starts with understanding how the river works and how changes to the basin's climate have thrown a wrench into how its water is managed.

The Colorado River, like other bodies of water in the West, is mostly fueled by snowpack runoff. The mountains above the river collect snow between late fall and early spring, which melts into the river. However, the relationship between snowpack collection and what the river receives from the snowpack is off, as drier conditions mess with snowmelt efficiency.

Digging through records, Shawcroft found, in 1929, the basin's snowpack was 132% of normal and it led to 135% of normal runoff. This is representative of the traditional process.

That surprised him because he's seen how recent years have played out. Water years now yield runoffs worse than the snowpack collection — far worse in some cases.

- 2020: 107% snowpack; 61% runoff.

- 2021: 89% snowpack; 37% runoff.

- 2022: 90% snowpack; 63% runoff.

- 2023: 161% snowpack; 140% runoff.

The most recent outlook indicates the basin could end up with an 87% runoff despite better snowpack figures throughout the region.

"Runoff is no longer the way it was historically," he said.

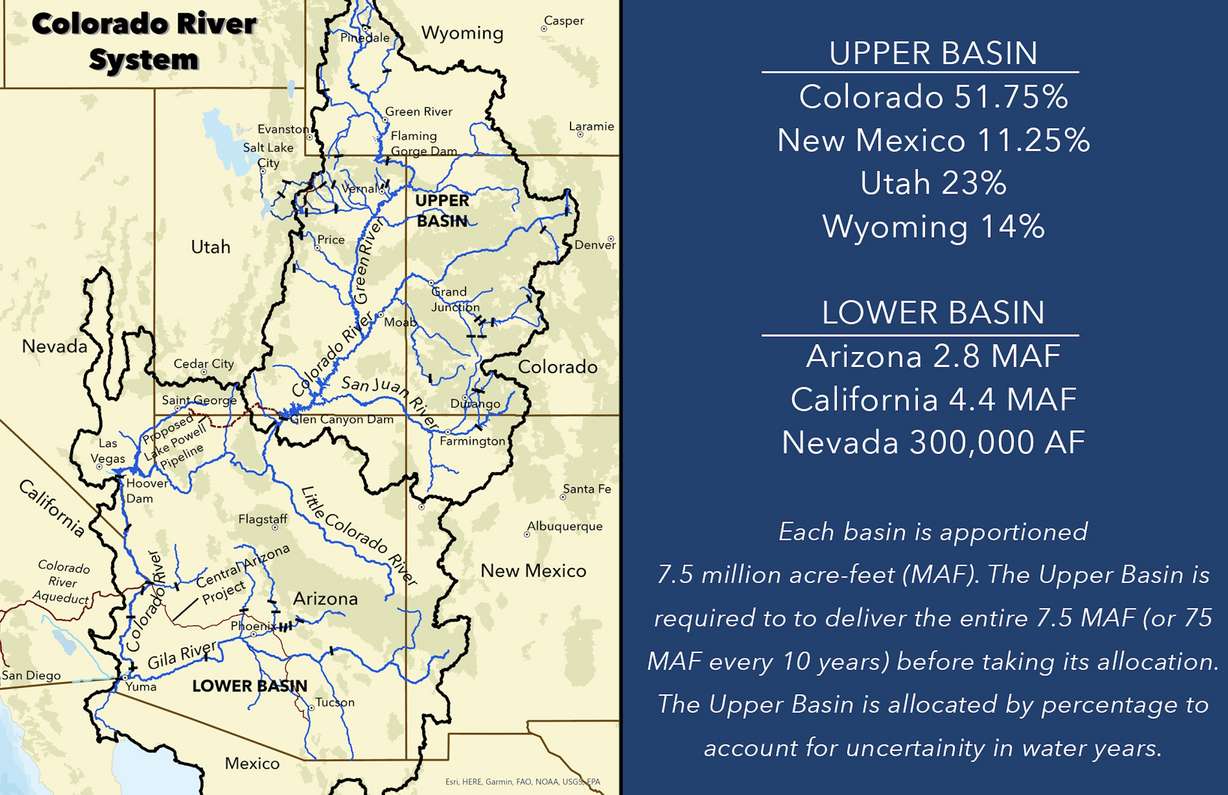

This ties into overconsumption. The Colorado River's water is uniquely divided because of longstanding disputes over who gets the water. The 1922 agreement settled a debate over complex water laws.

Today, Upper Basin states receive a share of the water that flows into Lake Powell, while the Lower Basin states receive an allocation from Lake Powell and Lake Mead discharges. An operation schedule is formed through forecasts, dictating how much is released from reservoirs based on what it is expected to regain from the snowpack.

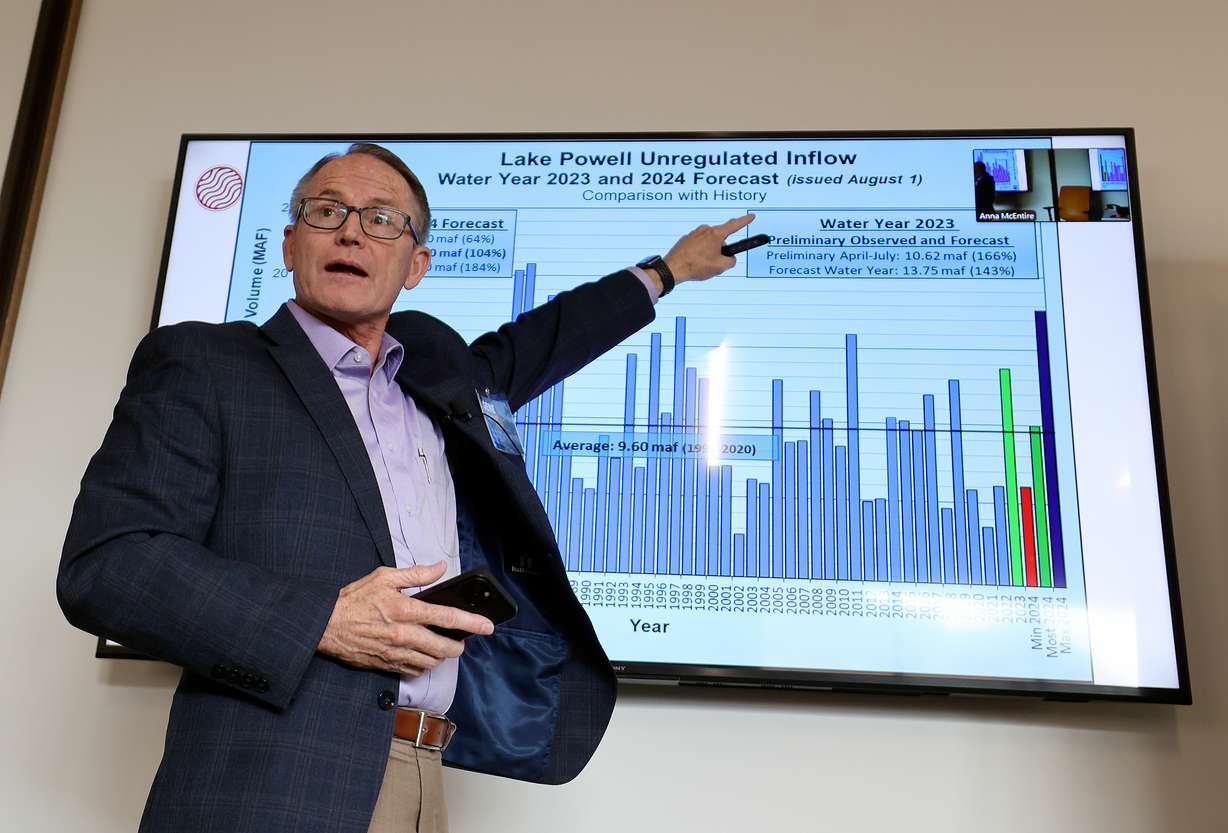

Yet the poor runoffs meant reservoirs didn't receive as much water as projected, causing the reservoirs to drop to levels that threatened their ability to function. All of this is visible in the data, says Jack Schmidt, director of the Center for Colorado River Studies at Utah State University.

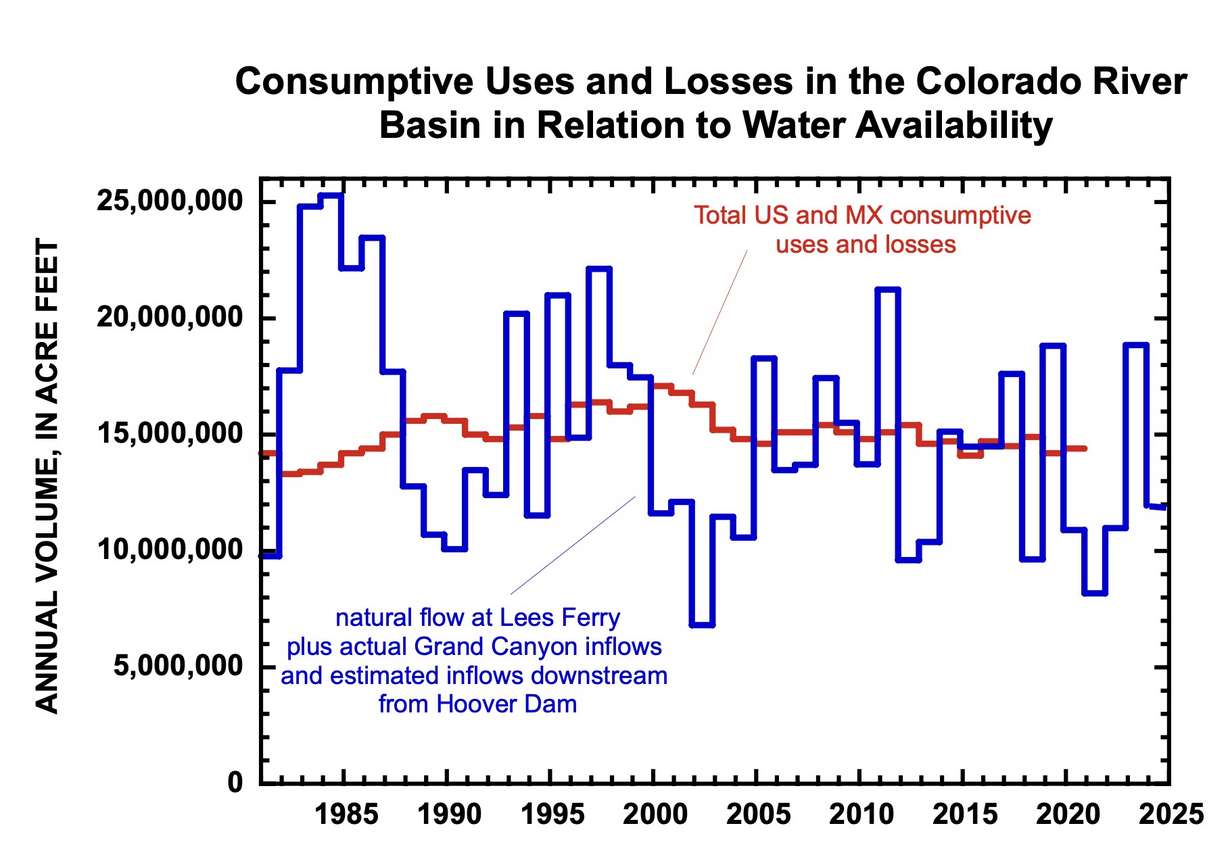

He led a study last year that determined the basin consumed an average of 15.1 million acre-feet of water between 2000 and 2020, based on consumption data and evaporation estimates. It only gained an annual average of about 13.6 million acre-feet of water during that time. A large chunk of the reservoirs' decline came in the early 2000s before governments realized this problem, while reservoirs haven't dropped as much year-to-year more recently.

"(A drying climate) is the ultimate cause of the problem — there's no question. But the proximate cause of the crisis is the disparity between the natural supply for each year and how much we use as a basin," he said.

What happens now

The seven states agreed on a short-term plan to address concerns over Lake Powell and Lake Mead, which the federal government accepted this year. The agreement is expected to reduce consumption by at least 3 million acre-feet of water ahead of the post-2026 plan.

The two sides agree there's also an annual evaporation and transmission loss rate — or "structural deficit" — of about 1.5 million acre-feet in the system. However, the Upper Basin and Lower Basin states are divided over how supply challenges are addressed.

I think we all understand that we're in a better position to come up with a solution than have a solution that's forced upon us.

– Gene Shawcroft, chairman of the Colorado River Authority of Utah

The Upper Basin plan doesn't change the distribution of upstream water, but it calls for release reductions based on the capacity of the two reservoirs. For example, 8.1 million to 9 million acre-feet would be released from Lake Powell every year when it is between 81% and 100% full, but as little as 6 million acre-feet of water would be released per year when it's less than 20% full.

The Lower Basin states agree there should be reductions when the reservoirs are lower; however, their plan also calls for reductions within the Upper Basin so more water can flow into the reservoirs.

"Most fundamentally, this framework commits stakeholders to the simple principle that when less water is available in the system, less water should be taken from the system," the Lower Basin states wrote in the plan.

The divide became evident during a meeting this January, Shawcroft said. He believes the 1.5 million acre-feet for the structural deficit loss is one of the factors in the different alternatives. There's also a divide between Lower Basin states, as Arizona pushes for cuts based on use and California pushes for cuts based on priority.

Department of Interior and Bureau of Reclamation officials said in March that discussions will also include feedback from Mexico and tribal nations that also have a stake in the river water, an aspect that hasn't been included in the past. They added they would prefer to publish a draft environmental impact statement by the end of the year.

It's unclear if or when the states may have a consensus proposal to send by then, but the federal government could step in and determine dam management if the entities don't come up with one. It's a possibility the states would like to avoid, Shawcroft said. In fact, he believes that is why all the entities have been willing to work through differences as they negotiate on a long-term plan.

"I think that's what keeps us at the table and keeps us talking in spite of the challenges that are out there," he said. "I think we all understand that we're in a better position to come up with a solution than have a solution that's forced upon us."