Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

PROVO — A BYU professor and his students recently traveled to Indonesia to to help prepare people for natural disasters through research and applying risk-reduction strategies.

Risk reduction is also crucial in Utah to prepare people for when a big earthquake eventually hits.

Geology professor Ron Harris took three students to Ambon, Indonesia, in August where for more than two weeks they gathered data to better understand how certain areas will be affected by earthquakes and other natural disasters. They met with village leaders and local government to educate the area about the risks of where they live and how to prepare for the next natural disaster.

Indonesia consists of more than 17,000 islands that are located near several active faults full of tectonic activity leading to frequent earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic eruptions.

The people in Indonesia are aware of the risks associated with where they live, but they don't always know how to prepare for it, according to Harris, which is where research and risk-reduction strategies come into play.

"There's nothing we can do about stopping the tsunamis, or the earthquakes, or the volcanoes, either there or here. So the only thing we have control over is preparedness," Harris said. "We have already saved thousands of lives in Indonesia just because of that — of focusing on preparedness which is the part that's usually left out."

There's nothing we can do about stopping the tsunamis, or the earthquakes, or the volcanoes, either there or here. So the only thing we have control over is preparedness.

–BYU geology professor Ron Harris

Geology student Shayna Orme said part of the students' efforts in Indonesia was to educate everyone they came across on simple things they can do to prepare for risks around them. They also gathered data on how the ground would be affected when it started shaking and who would be most impacted by the shaking.

The students used HVSR, a new method of gathering information about the subsurface that is simpler than previous methods. Orme said this new method expands their ability to reach more people and help more because they can gather data easier and in more places to better make recommendations for risk reduction.

The students are using the data they collected to make a hazard map of Ambon to see which areas and buildings are most in danger of shaking and collapsing. Geology student Brierton Sharp said some of the places that are most in danger are highly populated, such as the hospital and government buildings.

Because of this data, Harris and his students checked out these high-risk areas and found that the hospital and the governor's office building showed damage from a 2019 earthquake. These buildings are now even more in danger of collapsing in the next earthquake because of their location and the damage they have already sustained.

Preparedness is key

Harris has traveled to Ambon several times to conduct various research in geology and train locals in risk reduction. One such village he visited lived below a river that had been naturally dammed up from a landslide.

"Because we had trained the people who live there that you can actually prevent disasters instead of just waiting until the disaster is over and going in with relief to clean up, they immediately started to prepare the people who lived below the dam for the inevitable evacuation," Harris said.

The village made evacuation signs and had a few drills to prepare.

Not too long after, the dam broke. The village's alarm sounded and they only had seven minutes to evacuate, but because the village had been prepared, hundreds of lives were saved and a massive disaster was prevented.

Harris compared preparedness for a disaster to doing the work during peacetime before the war starts.

An earthquake is a rapid onset hazard, meaning there is no warning for when the hazard will come. Once the earth starts shaking, time for preparation is over.

"Because then it's too late," Orme said. She suggests people start devising their plan for what they will do when an earthquake starts so they are prepared and can prevent catastrophe.

One risk-reduction strategy Harris and his students implemented for tsunamis was educating locals on the 20-20-20 rule: if an earthquake lasts for more than 20 seconds, you have 20 minutes to get to higher ground of at least 20 meters. Although there is no warning for an earthquake, an earthquake is a warning for a potential tsunami if you live near the coast.

Harris said through this rule, many lives have been saved by people knowing when, where and how to evacuate to be safe from tsunamis. Other evacuation drills and training have helped save people from a volcanic eruption too.

"These are just simple things. We're just barely getting started. This is the tip of the iceberg," Harris said of risk reduction.

How does Utah shape up?

In Utah, many people are aware of the potential earthquake scientists have predicted will occur. But because the risk isn't as immediate as it is in Indonesia, many Utahns don't prioritize earthquake readiness.

"A lot of BYU students aren't from high-risk areas with earthquakes, so they don't know what to do," Miller said. Some students don't know they live on a fault line, and others don't care because they think they'll be out of Utah in two years so they'll be fine as long as an earthquake doesn't happen in the next two years.

"But we don't know that, and we are pretty overdue for one."

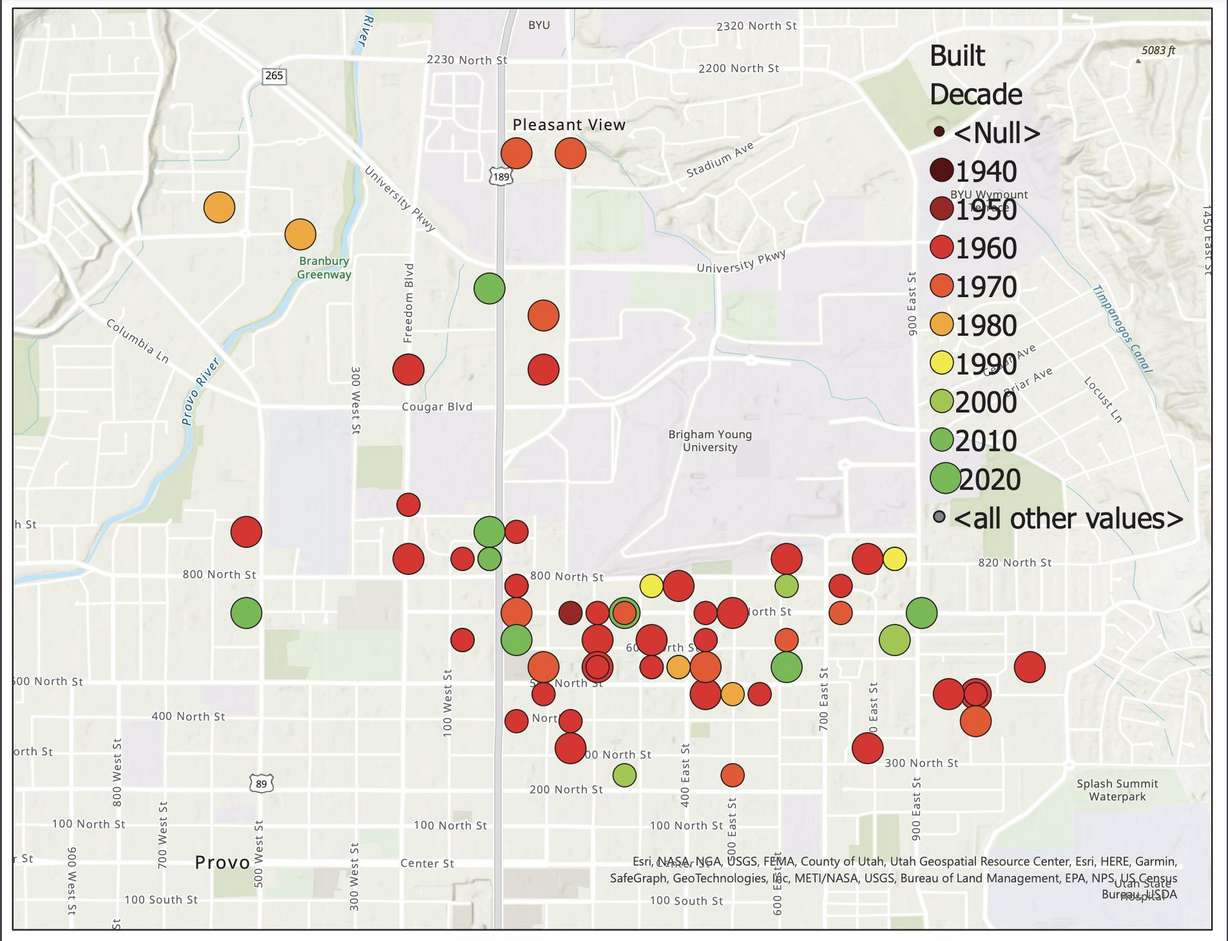

Miller did not visit Indonesia with Harris, but she does work for him doing research on the earthquake readiness of housing in Utah Valley. She created a map of properties that were formerly BYU-approved and found almost 75% of BYU housing is not up to seismic code.

"I think it's really important to let students know where they are living," Miller said, to keep students aware of the risks they live in.

Much of the housing in Utah Valley was built before the first seismic safety codes were put in place in the 1970s. Harris said if a building was built before 1985 and hasn't been retrofitted, most likely it is not earthquake ready.

Similar to how landlords in Utah are required to disclose the possibility of lead-based paint in housing built before 1978, Harris believes there should be a law requiring any property built before 1985 to disclose if it is not up to seismic code.

"There's really nothing that's making a landlord make sure — it's not like black mold where they legally have to be doing something about it," Miller said.

If a building is made out of brick, doesn't have insulation or is built on top of a parking garage, Miller said those are all signs the building is most likely not safe in an earthquake. In buildings that aren't up to seismic code, ducking and covering won't do much to keep you safe when the building collapses.

Students can't make changes to the properties they rent, and because seismic renovations are expensive and don't benefit the landlord directly, many landlords just leave the property unsafe for earthquakes, Miller said.

It's so important people, but especially students, know what they're living in and know the risks.

–BYU geology student Shayna Orme

"It's so important that people, but especially students, know what they're living in and know the risks," Orme said.

Orme and other geology students hosted a booth in the Wilkinson Student Center at BYU educating students on the fault zone they live on and the predicted 7.2 magnitude earthquake it is overdue for. She said the students talked about how California has been retrofitting buildings and updating seismic codes to prepare for earthquakes, but Utah hasn't done as much.

Miller's data also shows about 60% of schools in Utah Valley are not built to seismic code either. Although the Great Utah ShakeOut has been encouraging earthquake drills in schools for years, not all schools in Utah have yearly earthquake drills to teach children what to do when an earthquake hits.

Heritage sites, especially ones from the pioneer era, need to be retrofitted if we don't want to risk them collapsing and potentially injuring people, Miller said.

Lives will be saved if buildings are rebuilt or retrofitted to survive earthquakes, Harris said.

BYU and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have been recently renovating or retrofitting buildings for earthquake safety.

Related:

The old dorms known as Deseret Towers were rebuilt into Heritage Halls about 10 years ago and the Harris Fine Arts Center is set to be demolished soon with plans for a new arts building in its place.

The Church of Jesus Christ retrofitted the burned Provo Tabernacle with seismic upgrades when it rebuilt it into the Provo City Center Temple in 2016 and the Salt Lake Temple is currently undergoing seismic and structural renovations.

What Utahns can do to prepare

"The more people that know about the hazards, the more people can advocate for change. Tell the city, tell the state, "Hey, we are concerned about this, we want to see you guys take action to do something about it,'" Orme said.

The more people that know about the hazards, the more people can advocate for change. Tell the city, tell the state, 'Hey, we are concerned about this, we want to see you guys take action to do something about it.'

–BYU geology student Shayna Orme

Sharp said one of the best ways to prepare for earthquakes is to secure furniture and other nonstructural items that might easily fall over when the ground shakes, such as bookshelves, hanging items or televisions.

The majority of injuries in earthquakes occur from things falling, so bolting them to the wall or ensuring those items aren't next to beds is crucial to earthquake safety.

Thinking about what to do when an earthquake hits and doing earthquake drills in schools, businesses and as a family are also important, Orme said. She encourages being prepared by educating yourself and devising a plan.

Harris and his students started a nonprofit called In Harm's Way which is dedicated to reducing injury, saving lives, and encouraging self-reliance by "educating individuals about the effects of natural hazards worldwide through disaster risk-reduction activities before the event happens."

Instead of just waiting until the disaster happens and putting money into disaster relief, being proactive and focusing on prevention allows In Harm's Way to make a bigger impact. "An ounce of prevention is worth tons of disaster relief," its motto says.

Harris said he has enjoyed seeing the prevention efforts in Indonesia grow and take on a life of their own.

One city where they helped implement the 20-20-20 rule started a parade tradition where some people ride bikes and dress up in blue as if they are a wave of water and chase the others to the evacuation point. Other cities hold records of people racing to the evacuation point the fastest, all to help encourage people to prepare for disasters.

Although risk reduction has a life of its own in Indonesia, the same can't be said for Utah yet. Harris and his students hope Utahns will become more aware of the risks around them and prepare themselves for when the earthquake comes.

The focus on bridging the gap between science and people is just a super important thing that a lot of people forget. We don't do science just for science's sake, we do it to help people," Miller said.