Estimated read time: 13-14 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah's congressional delegation ran the gamut of Republican responses to former President Donald Trump's all-out effort to overturn the 2020 presidential election results that ultimately led to a deadly assault on the U.S. Capitol one year ago.

The varied perspectives of the state's all-GOP contingent in Washington during those turbulent months leading up to that dark day in American history and its aftermath are emblematic of the Republican Party.

Trump urged his supporters at a rally last Jan. 6 to "fight like hell" for his presidency, and a mob stormed the Capitol trying to stop Congress from certifying states' electoral votes for Joe Biden. It was the worst domestic attack on the seat of government in U.S. history.

A year later, the country continues to see big partisan differences over whether Biden was legitimately elected. Trump and his followers continue to sow doubt over the presidential election results.

"What's unfortunate is the fact that since that time these narratives about problems with the vote that really have no basis in fact even after recounts and audits and everything else, there seems to still be a very politicized reaction to the result," said Chris Karpowitz, co-director of the Center for the Study of Elections and Democracy at Brigham Young University.

"That doesn't bode well for the future because I can imagine that we'll have elections that are even closer."

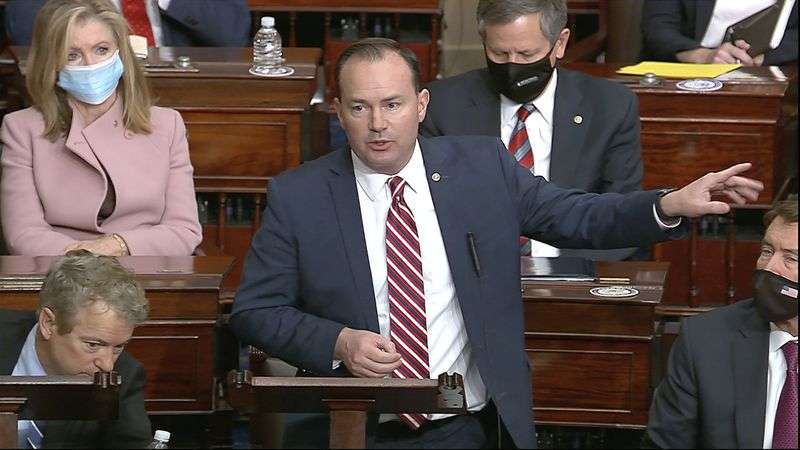

Utah Sen. Mike Lee says the key to ensuring legitimate presidential elections is to follow the Constitution, which gives states that authority, not the federal government.

"Any time we hold to that document, we're well-served by doing so," he said. "Where we deviate from it, problems sometimes arise."

Though now more than a year removed from the 2020 election, it remains on the forefront of American politics.

Many conservatives haven't let go of the fact that Trump lost the election. A bipartisan House committee is investigating what led to the Jan. 6 insurrection. States are passing election laws because of it. State elected officials are under fire for simply doing their jobs.

The 2020 election could be an issue in this year's midterm election. It and the Capitol riot will most certainly be more of an issue in the 2024 presidential election if Trump runs again. Meanwhile, Republicans are wrestling with Trump's place in the party.

All four of Utah's congressmen and one senator face reelection this year. Their words and actions surrounding 2020 also could play into their races.

Utah responses to 2020 election, Capitol incursion

Five-term Rep. Chris Stewart and freshman Rep. Burgess Owens largely toed the party line in supporting Trump. Both joined 139 House members in objecting to the certification of Pennsylvania's electoral votes. Stewart and Owens also voted against forming a bipartisan congressional committee to investigate the Jan. 6 attack.

Rep. John Curtis, who has served since 2017, and freshman Rep. Blake Moore voted to certify the presidential election results and in favor of the investigative committee.

Utah's four congressmen all voted against impeaching Trump.

Sen. Mitt Romney was the most forceful member of the state's delegation in directly blaming Trump for the Capitol incursion, saying "you can either be a fire extinguisher or a flamethrower. And President Trump has been a flamethrower." Romney voted to certify the election results and joined six other Republicans in voting to convict Trump of inciting an insurrection.

Lee also voted to certify the electoral votes but did not vote to convict the former president in the Senate trial, arguing the proceeding was unconstitutional because Trump was no longer in office.

What is Congress' role in certifying an election?

Among the state's all-Republican congressional delegation, Lee was closest to — though not directly involved with — the Trump campaign's effort to contest the election results and find a path to keep Trump in office.

Lee said last January legitimate concerns were raised with regard to how some of the key battleground states conducted their presidential elections. He advised Trump on his legal challenges to the results.

In an interview Wednesday, Lee said he never felt any pressure from the White House to find a way for Trump to hold on to the presidency.

"At no point did I feel pressured by them to do that. I wasn't doing any of this with any particular end in mind. I wasn't determined to achieve a particular result as far as the election," he said.

"My only job there was to fulfill my constitutional responsibility and to advise my colleagues as to what that responsibility was. My allegiance first, last, foremost, always is to the Constitution."

Lee received a two-page memo from the White House the weekend before Jan. 6 outlining a path where Vice President Mike Pence could hand the election to Trump because seven states had submitted dueling slates of electors to Congress, split between Trump and Biden. Pence could simply set those states aside on Jan. 6 and count only electors from the remaining states, it claimed.

After receiving the memo, Lee called state officials in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Michigan and Arizona, all swing states that Trump lost. He said he found in conversations with governors, attorneys general, secretaries of state and legislative leaders in those states that not one was willing or inclined to decertify or recertify their electoral votes.

Lee said his study of the Constitution found that Congress' only role in a presidential election is to open and count the electoral votes, and that he told Trump early on that he needed to respect the results.

Asked what he sees as the major contributing factors leading to the Capitol takeover, Lee pointed to the Constitution. "The constitution certainly provided answers on Jan. 6 and it continues to provide the answers today," he said.

So, did Trump not hold to the Constitution?

"At end of the day, Congress was able to fulfill its role in opening and counting the electoral votes. The violence that happened that day was wrong, it's very, very wrong. It's a shame that those wrong acts are being used by some to justify other wrong acts in the form of political excesses," Lee said.

Asked if Trump not accepting the election results led to the Jan. 6 riot, Lee said the former president didn't commit any crimes.

"A lot of things could have gone differently. I think a lot of people should have conducted themselves differently that day. President Trump didn't commit any criminal acts that I'm aware of. The people who broke the law are the ones who are to blame, those who committed violent acts and broke into the Capitol are to blame," he said.

Another Jan. 6 coming?

A new Washington Post-University of Maryland poll shows 34% of Americans say violence against the government is justified at times. It also shows how partisan those views are, with 40% of Republicans, 41% of independents and 23% of Democrats saying violence is sometimes justified.

A CBS News/YouGov poll found 68% of Americans see the events of Jan. 6 as a sign of increasing political violence, while 32% believe it was an isolated incident.

Jason Perry, director of the University of Utah's Hinckley Institute of Politics, said there's nothing to suggest an uprising couldn't happen again.

Distrust in government institutions and the electoral process remains pervasive among some Americans. He said it's incumbent on elected leaders to reassure voters not only that their ballot matters but that elections are not being manipulated.

"If we don't have some course correction, those elements still exist. They clearly do. We have to guard against that," he said. "We saw clearly on Jan. 6 what can happen when it is unchecked and when fuel is added to it. It can happen again."

David Becker, executive director and founder of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research, fears violence could erupt in state capitols over the 2022 midterm elections and in future elections as well.

"Every day that goes by I only become more concerned that we're heading toward something our democracy has never had to deal with before," he said during a virtual briefing with reporters this week.

Americans the past decade have been fed a steady diet of partisan information that those with whom they disagree politically are their true enemies, more so than foreign adversaries such as Russia.

"When you start believing that your neighbors and your friends and your fellow citizens are your enemy because they disagree with you on policy, then you start being able to rationalize behavior that would normally be irreconcilable with any kind of principles," said Becker, who worked as a lawyer with the Department of Justice Voting Section in both the Clinton and George W. Bush administrations.

Trump election denial

What happened on Jan. 6 was a culmination of slowly simmering dissatisfaction, distrust and confusing information to which gasoline was added and that Trump did nothing to quell, Perry said.

Nancy MacLean, a Duke University professor of history and public policy, said if the country doesn't reckon with the deep historical roots of what happened this time last year, those events could be prologue to a far worse outcome in the future.

The House investigative committee, she said, has identified three areas of activity: a large, less complicit outer circle of avid Republican voters who believed the "big lie" and turned into rioters; a smaller number of committed white-power insurrectionists; and an inner circle that strategized to overthrow the election, exploiting federalism to achieve its ends.

"Each of these elements is the product of decades of intentional cultivation," MacLean said.

Karpowitz said the major contributing factor to the Jan. 6 riot was an incumbent president who did not want to accept the outcome of the election. It was a close election but not the closest in U.S. history.

Al Gore lost to George W. Bush in 2000 by 537 votes when the U.S. Supreme Court ended the recount in Florida. Gore chose to accept the results though there were things he could have done to cast doubt over the outcome.

The Trump campaign and others filed dozens of lawsuits and cast doubt over the outcome across the country. Nearly all the suits were dismissed or dropped for lack of evidence. Becker said that when people stop accepting the rule of law, violence becomes the next natural stage.

"Elections are always messy to one extent or another, but we've always taken pride in the peaceful transfer of power and in the notion that both winners and losers respect the verdict of the voters," Karpowitz said.

"Both of those things have been called into question. We did not have a peaceful transfer of power. We had violence on Jan. 6. Over the last year, instead of coming to a common agreement about the outcome of 2020, reactions have been polarized. It's unhealthy if either political party fundamentally doubts the outcome of a presidential election."

The 2020 election was also unusual in that it was held in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, yet voter turnout hit a record high. Despite those challenges, Karpowitz said the 2020 election was "in many ways a democratic triumph, little 'd' democratic." Trump's Department of Homeland Security called it the most secure election in U.S. history.

But Becker said if Republicans continue to tell voters that elections aren't secure and that their vote doesn't count, they might not bother to vote at all. He said it's hard to get them to turn out if they're repeatedly told elections are rigged.

Safe and secure elections

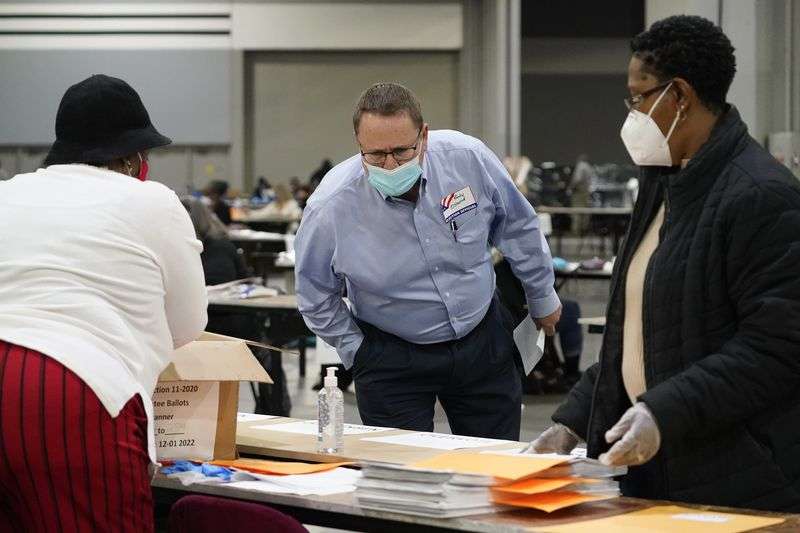

The controversies that arose in 2020 mostly had to do with how states handled elections in the middle of a public health crisis. While some accommodations were made for people to vote safely, rules around 2020 were transparently and publicly made years or months before Election Day.

Those questions pushed some states in which Trump lost, including Arizona, Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, to conduct recounts or audits of the 2020 election.

In Utah, a now-former Republican lawmaker called for an independent forensic analysis of the 2020 election, even though Trump won the state handily. It drew a swift rebuke from Gov. Spencer Cox and Lt. Gov. Deidre Henderson, who oversees state elections. Both said they were frustrated by the misinformation and sought to assure voters there is no evidence of election fraud in Utah.

"This was a nanosecond before a response came," Perry said.

Perry said he worries that people will disengage from the political process as a result of confusing and false information about elections.

"What we need now more than ever is for people to engage, for people to continue to be involved in the political process, continue to hold elected officials accountable, be engaged in efforts to strengthen our country. Right now, it's entirely too easy to try and bring it down," he said.

Though no states reported illegal voting in the presidential election sufficient to have changed the outcome, many states across the country passed voting laws that critics say restrict ballot access. Some of them disempower nonpartisan election officials and make it easier for state legislatures to step in to impose their will.

Karpowitz said that's "potentially worrisome" if legislatures use that power for partisan ends, whether Republican or Democrat.

Becker said it's appropriate for states to look back in good faith at election laws provided there is bipartisanship and that the election officials are driving the changes to improve the process.

Election workers at risk

"We're still talking about the 2020 election, which is simply amazing. It's exhausting for election officials," he said, adding that those officials did a remarkable job.

Not only are election workers worn out, but they continue to be harassed and threatened repeatedly by Trump supporters, Becker said. His organization formed the Election Official Legal Defense Network four months ago to ensure that election workers can receive pro bono advice and legal protection from threats and harassment. The organization has already connected several election workers with lawyers in more than one state, he said.

"We're sitting here well over a year after the election and nearly a year since the insurrection and we are still dealing with the aftermath of the ongoing election denial and the attacks on democracy," he said.

Republican elected officials in states like Georgia, where Trump claimed voter fraud, courageously followed their laws despite tremendous pressure, including from the former president pushing them to find votes for him.

Karpowitz said he worries less about political violence than what might happen at the state level in a close election.

"If Georgia is close again in 2024, would the elected officials in Georgia or in Pennsylvania or in Wisconsin or in Arizona, would they defend the integrity of the election or would they yield to the political pressure?" he said. "That is where my concerns would lie going forward."

Though 2022 is not a presidential election year, it could be a pivotal midterm election. Republicans appear likely to win back the House and possibly the Senate. While the Jan. 6 insurrection could be an issue this year, it would be more so in 2024, especially if Trump is the GOP nominee.

And while Republicans might coalesce around that possibility, they continue to disagree on the role of Trump going forward and to what extent should the GOP be "wholly and completely" the party of Trump, Karpowitz said. That, he said, is a question that Republicans are grappling with.

"Fundamentally, it is remarkable to me that Donald Trump actually has a political future given what happened on Jan. 6," Karpowitz said. "There were many Republicans who that day and in the immediate aftermath said, 'This has to be the end of Donald Trump's political career,' but it doesn't seem to have been. That's a remarkable fact."