Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.

SALT LAKE CITY — Seventy-five years ago Thursday, newspapers in Utah and across the globe flashed headlines about the atomic bomb drop on Hiroshima, Japan. Days later, they reported similar headlines after the bombing of Nagasaki, Japan.

Within a month, Japan surrendered and World War II was officially over after six years of global fighting.

Here’s a look into how these events were covered in local newspapers at the time and how the personal stories of two of the most devastating bombings in world history eventually made their way to Utah.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

On Aug. 6, 1945, a B-29 bomber plane circled over Hiroshima in southern Japan and dropped an atomic bomb that killed thousands instantly when it was detonated about 2,000 feet above the city. Death tolls from that day still range widely. History.com lists 80,000 total deaths; BBC has it as 140,000.

Thousands more were killed three days later when a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki — about 186 miles southwest of Hiroshima. Again, figures of the number of people killed that day vary, ranging from 40,000 to 74,000. That, of course, doesn’t account for the many more who would end up dying in the following days, months and years from injuries or radiation tied to the blasts.

A photo caption under a map of Hiroshima published in the Aug. 6, 1945, edition of the Salt Lake Telegram may have summed it up best: “Power of the universe was unleashed on Hiroshima.”

The lead article in the paper that evening — a wire story from United Press International — reported that the blast was equivalent to exceeding 20,000 tons of TNT.

“The war department reported that ‘an impenetrable cloud of dust and smoke’ cloaked Hiroshima after the first atomic bomb crashed down. It was impossible to make an immediate assessment of the damage,” the article reads, in part.

President Harry S. Truman, who had taken office after President Franklin D. Roosevelt died in April of that year, said at the time that the bomb was an answer to Japan refusing to surrender. He also threatened to release an even worse attack if the country didn’t give up.

“It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe. The force from which the sun draws its power has been loosed against those who brought war to the far east,” Truman said.

A second article described how over 500 other B-29 planes dropped less powerful bombs on four other cities that day, as the U.S. war against Japan continued.

There isn’t really anything that indicates how Utahns responded to this at the time, which is likely due to not having access to instant news events like we’re benefitted with today. News of the bomb attack was delivered through radio and newspapers, and visuals of the scene weren’t immediately available after the attack. The images in Utah papers that day were maps of Japan and photos of Truman.

The world discussion of the attack was more evident the days after. The Provo Daily Herald ran a pair of wire stories on the front page the following day that showed the immediate questions that arose 75 years ago.

One article mentioned that Japanese propaganda stations broke off from traditionally reporting that there was no military damage after an attack to reporting widespread damage in Hiroshima. It was so devastating that the country’s media went in another direction.

“Destructive power of this new weapon cannot be slighted,” the report quotes Japanese media as saying. “By employing a new weapon designed to massacre innocent children the Americans have opened the eyes of the world to their sadistic nature.”

Indeed, questions of what a new nuclear bomb age meant were quickly brought up in newspapers, as well. The other front-page wire article weighed the good and evil of it.

“It is the most terrible engine of destruction ever conceived. It may end the Japanese war soon … but when the bomb’s work is done, its makers hope to convert its power to the arts of peace, and the enforcement of peace,” the article states. “Upon realization of this hope hangs the fate of humanity, atomic power could remake the world; it also could destroy it.”

As people were weighing the future of atomic weapons, the U.S. used a second bomb on Nagasaki on Aug. 9, 1945. A headline in the Aug. 11, 1945, edition of the Deseret News called it a “worse blast” than Hiroshima.

At about the same as these attacks, reports surfaced that Japan was on the brink of surrendering a war that began with the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

How Utah reacted to the end of World War II

The celebrations over defeating Japan actually happened a bit prematurely. Utahns appeared to have joined the nation in celebrating Victory over Japan, or V-J, Day on Aug. 15, 1945 — despite the fact fighting was still going on and Japan wouldn’t officially surrender until a couple of weeks later, on Sept. 2.

There are newspaper articles that report this. For example, the Salt Lake Telegram published on Aug. 14, 1945: “Today is not V-J Day. Despite the celebrations at the Jap admission of complete defeat, until President Truman proclaims victory, there will be no V-J Day.”

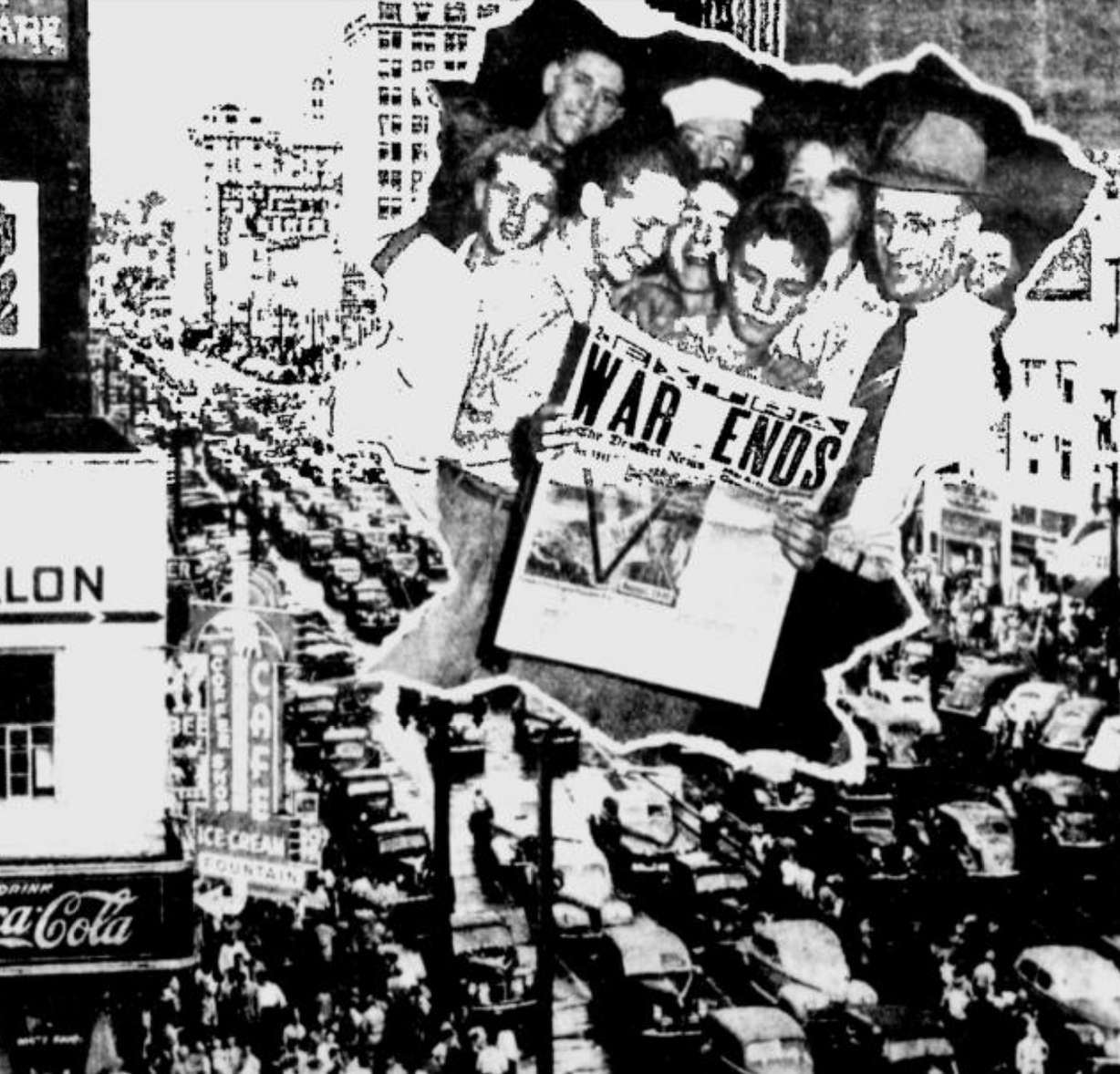

A Deseret News article on Aug. 15, 1945, documented the celebrations happening regardless. In an article with the headline “Salt Lake goes wild in peace celebration,” it was reported that newspapers with the massive headline “WAR ENDS” spread across downtown Salt Lake City.

“Today a Main Street littered with paper marks the scene of merry-making, which began to subside at 3 a.m. Local citizens had ‘blown their tops’ and were ready for bed and rest necessary to help them carry on for two more days of celebrating,” the article reports. “What lies in wait during today and tomorrow, proclaimed by acting Governor E.E. Monson as holidays, is purely speculative. No organized program had been arranged this morning by the city committee headed by Commissioner John B. Matheson or the Chamber of Commerce.”

Celebrations continued after the war officially ended. A Sept. 3, 1945, edition of the Deseret News reported that thousands were expected for an interfaith meeting "of thanksgiving and peace" at the Salt Lake Tabernacle.

After the war

There were people opposed to using atomic weapons in 1945, but efforts to avoid nuclear warfare grew after World War II. The Atomic Heritage Foundation notes that an August 1945 Gallup poll found 85% of Americans supported the bombings while 10% didn’t. Compare that to a 2013 Gallup poll where 56% of Americans favored the U.S. and Russia reducing nuclear weapon supplies amid talks at the time.

Americans were aware of the destruction but probably didn’t know the exact horrors of the atomic bomb on a human scale until years later. In fact, articles of survivors visiting Utah to share their stories of living through the bombing appeared in newspapers as early as 1951.

The Salt Lake Telegram reported on Dec. 3, 1951, that Nasako Shoji, a former Hiroshima University associate professor shared her story with an audience in Salt Lake City. Shoji left Hiroshima on the morning of the attack and was about 6 miles from the city when the bomb was dropped.

“From my friend’s house I looked into the clear blue sky and saw a ball of white light flash into the size of a full moon,” she is quoted as telling the crowd.

When she returned to the city, she found “crowds of refugees, burned, maimed, barely alive, filing in a seemingly endless procession, of the flames which had covered up the city.”

Since the end of the war, Hiroshima and Nagasaki became reminders of the devastation of nuclear weapons. Flash forward to 2020, as survivors gathered to mark the anniversary. Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was confronted by some survivors seeking to permanently ban nuclear weapons, according to the Associated Press.

Said Abe: “Japan’s position is to serve as a bridge between different sides and patiently promote their dialogue and actions to achieve a world without nuclear weapons."