Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note:This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.SALT LAKE CITY — When it comes to the history of the nation’s vast public lands, what’s often missing from the narrative is the role women played during the early years of the U.S. Forest Service, and the increasing role they have played in overseeing the lands for the past five decades.

“For most of its existence, the Forest Service has had a reputation as a 'good ol’ boys' organization, due in large part to its reliance on a male workforce,” said Richa Wilson, an architectural historian for the U.S. Forest Service.

During a presentation at the Utah State History Archives Wednesday, Wilson showed early clippings of advertisements seeking men to enlist in the Forest Service. She also shared the contact between correspondents of those who worked behind the scenes because they were practically secret employees.

One early advertisement read, “Men wanted! A ranger must be able to take care of himself and his mules under very trying conditions; build trails and cabins; ride all day and all night; pack, shoot, and fight fire without losing his head. All this requires a very vigorous constitution. It means the hardest kind of physical work from beginning to end. It is not a job for those seeking health or light outdoor work. Invalids need not apply!”

Sure, there were some women offered the same role as men relatively early in the agency’s history. In 1910, Eloise Gerry became the first woman to work as a researcher for the U.S. Forest Service. A decade later, Eula Bibo became the first woman lookout when she oversaw Boise National Forest. By the 1940s, women worked as radio operators and firefighters too, especially during World War II.

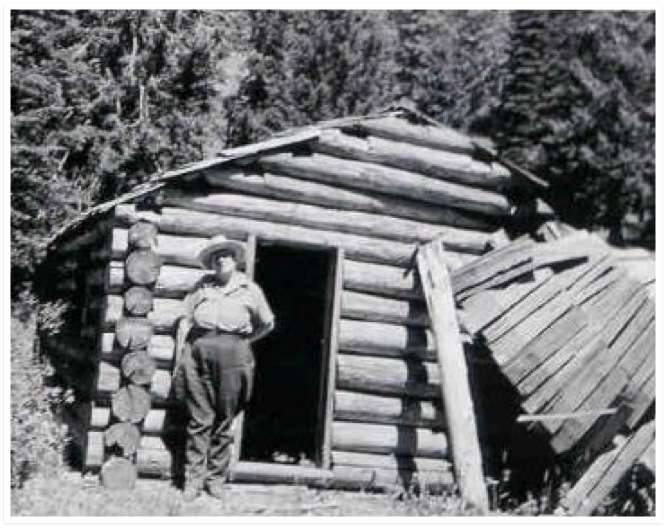

However, most female employees worked in U.S. Forest Service regional or forest headquarters away from the ranger district offices. There was one interesting exception: wives of forest rangers. In fact, they traditionally gave men a leg up on the competition because they were essentially under-the-table employees in the early years of the service.

Wilson referred these hires as “two for ones” because the wives of forest rangers weren’t on employee records.

Given an era where communication and transportation weren’t as easy as today, it was difficult for a ranger to go out on the land and also communicate to office headquarters. Since the ranger wives weren’t technically employees and they didn’t get paid, there are very little historical records of their work. Yet what is known is they usually communicated out important daily tasks.

They also took in weather reports, dispatched firefighters and equipment to fires and any other necessary work. If they had children, they would also serve as a homeschool teacher and all the other responsibilities of a parent, Wilson added.

She explained this became an unwritten rule in the hiring process of career positions that was picked up on early.

“In those earliest years, I don’t see anything specifically that says, ‘Well, he’s got a wife,' so therefore it’s more of this thing that kind of evolved as they realized, ‘Oh we’ve got these rangers with wives, and their wives are able to answer the telephone or radio or whatever. This guy over here doesn’t get as much done because he doesn’t have this kind of help,’” Wilson said.

As such, their husbands likely wouldn’t have been as productive or successful without them.

“It is an accepted fact … that it would be mighty difficult for the district rangers to function effectively without the women folks on deck,” Alonzo Briggs, who served a district ranger in Kamas in the 1930s, wrote in one of the correspondents Wilson reviewed.

Of course, the wives caught on to this, too. Delpha Noble, one of the many ranger wives during this era, wrote in another letter: “I did all his typing. I think he married me for my secretarial skills.”

The role women and minorities have played in the agency boomed drastically in the 1970s as the roles shifted in the Forest Service mirrored changes in the U.S. labor force; however, it took years for women to land higher-level positions within the agency.

In 1981, Deanne Shulman became the first female smokejumper. Women have played a growing role in leadership, too. Today, the Forest Service is led by Vicki Christiansen and Lenise Lago is the assistant chief of the agency. Nora Rasure is the Regional Forester for the Intermountain Region, which oversees Utah has its headquarters in Ogden.

Even Wilson herself became the first architectural historian in the agency’s history since joining the Forest Service in the late 1990s.

“As with every agency, our service is continuing to make sure our workforce is diverse,” Wilson said. “What that means for me, personally, is more often than not, now as opposed to 20 years ago when I started, I may be in a meeting with other Forest Service people and I’m not the only female. … I think that’s a real shift.”

And now their role isn’t as so secret.