Estimated read time: 13-14 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — U.S. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke’s plan to visit southern Utah next week will place him, and by extension the Trump Administration, in the middle of two bitter fights over public lands in the state.

One, a white-hot battle over the 1.3-million-acre Bears Ears National Monument in San Juan County, erupted last December when then-President Barack Obama created the monument at the request of tribal representatives and against the wishes of county and state leaders.

The other fight has simmered for two decades. It deals with an older and even larger monument, blamed by many in southern Utah for slowly strangling the life out of their communities. Yet the disagreement over Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is coming back to a boil even as tourism in the region sets new records year after year.

A review of economic indicators by KSL, including employment data, visitation statistics, tourism-related tax revenues and county building permit records obtained through an open records request, reveals both the struggles and opportunities facing places like Cannonville, Kanab, Boulder and Big Water.

The simmering dispute

An irritated Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, was sick of hearing about the values of southern Utah’s tourism economy. During a meeting of the state’s House Natural Resource, Agriculture and Environment Committee in late February, the lawmaker unloaded on his colleagues from Salt Lake City.

“People tell me there’s all kinds of jobs down there; everything’s going great,” Noel said. “I really kind of get a gutful of it up here, I really do. It bothers me because it sends a false premise.”

Noel represents House District 73, a giant swath of territory covering all of Kane, Garfield, San Juan, Wayne and Piute Counties, as well as pieces of Beaver and Sevier Counties. He chastised urban lawmakers for suggesting federal management of Utah lands has had a positive influence by driving visitors, and by extension their tax dollars, into the rural region he represents.

“I’ve lived there for 41 years. I’ve seen what’s happened down there and my ancestors have lived there for over 100 years and it’s not in a good condition as far as you say, as far as economically and what’s happening to families,” Noel said.

In recent years Noel has helped lead the charge in several high-profile efforts to take control of federal lands. Key among those lands is the monument at the heart of his district — Grand Staircase-Escalante.

The maligned monument

As designated by President Bill Clinton in 1996, Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument covered roughly 1.9 million acres. It’s bounded on the east by Capitol Reef National Park and Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, and on the west by Bryce Canyon National Park. The monument’s northern edge abuts the Dixie National Forest, while its southern extremity touches the Arizona border.

Wrapped within it sits a maze of twisted river canyons, eroded sandstone pinnacles and arches, relics of pioneer history and fossilized dinosaur bones.

Rep. Noel’s cry to turn over those lands to state management, or to at least prioritize cattle grazing, ATV use and mineral extraction, have support from people like Garfield County Commissioner Leland Pollock.

“200,000 acres would be a stretch, to say that there’s antiquities, things of value that meet the Antiquities Act criteria,” Pollock said. “What is it? It’s BLM range. It’s brush land. It’s sage brush.”

The Bureau of Land Management administers the monument, unlike most other Utah monuments which are instead operated by the National Park Service.

Prior to the designation two decades ago, a bitter fight had raged between the mining company Andalex Resources, Inc. and environmental groups over the company’s plans to extract large amounts of coal from the region. Andalex held federal mineral leases around the Kaiparowitz Plateau.

The wording of President Clinton’s declaration made clear those existing leases were to be honored. However, the company made the decision not to develop the resources and ultimately gave up the leases in exchange for $14 million from the Department of the Interior.

Miners were not the only ones with claims to the land. Ranchers also held leases that allowed them to graze their cattle over much of what is now in the monument. Those uses were largely respected and allowed to continue by the Bureau of Land Management, though some parcels were withdrawn from use.

Monument critics believe the coal reserves could still be developed, to the economic benefit of the region, were the federal land managers not standing in the way.

Recreation opportunities on the monument are expansive, though not without difficulty.

Unlike many national parks, where trails are paved and shuttle buses run on tight schedules, Grand Staircase-Escalante is almost entirely primitive. It holds just three established campgrounds: Calf Creek along state Route 12 between Boulder and Escalante, Deer Creek on the Burr Trail Road and White House on the Paria River. Roads to most popular destinations are unpaved and at times impassable due to weather or damage.

“They did not want tourism,” Pollock said. “The monument itself, they would tell me when I was first sworn in as a commissioner, ‘this wasn’t created for tourism. It was created to study science.'”

The popularity explosion

Want them or not, tourists are coming to Grand Staircase-Escalante in record numbers.

Visitation statistics maintained by the National Park Service show Zion led the pack of Utah parks in 2016, taking in 4.3 million people. Bryce Canyon, the state’s second-most-visited park, welcomed almost 2.4 million. Both figures are nearly double the visitation recorded in 1996, when Grand Staircase-Escalante was born.

BLM records show the monument has also almost doubled its annual visitation during the same period. It set a high-water mark of 923,236 visitors last year, placing it above even Canyonlands and about on par with Capitol Reef National Park.

The rate of visitation growth for Zion, Bryce and Arches accelerated sharply in 2013. Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute Director Natalie Gochnour noted that in recent years, the Utah Office of Tourism has heavily advertised the parks with the Mighty Five campaign.

“There’s a lot of money that goes into promoting our state and it’s proven to be very well invested … but you have to be really careful that you also invest in the quality of that experience,” Gochnour said. “Whether it’s roads or campgrounds or bridges or water treatment plants, amenities, you need to invest in the tourism infrastructure business to get a payback from it.”

In Washington County, home to St. George and the Zion gateway community of Springdale, taxes on short-term lodging and restaurant sales have followed a similar curve as the park’s visitation. Grand County, too, has shown strong tourism-related tax growth, boosted by visitors to Arches who also stay and spend in Moab.

The visitation spike has helped accelerate recovery in Washington and Grand Counties following the recession of the late 2000s.

“The tax revenues related to tourism and travel are going up, have been for the last five years,” Jennifer Leaver said. She works as a research analyst at Gardner Institute and has spent a good deal of time examining the economics of southern Utah. “Jobs have been either remaining flat or going up. Wages have been going up.”

But while Garfield County is home to Bryce Canyon, it has not seen quite the same boost.

Challenges of the tourism economy

The tiny town of Boulder is made up of little more than a few buildings and farms snuggled into the valley where state Route 12 and the Burr Trail meet on the southern slopes of Boulder Mountain. As of the 2010 Census, Boulder claimed a population of 226.

Yet it’s exactly where Blake Spalding and her partner chose to start their business, Hell’s Backbone Grill, shortly after Grand Staircase-Escalante’s creation.

“We really just built it up. This is our 18th season. We have about 45 employees that work with us year after year,” Spalding said.

Hell’s Backbone Grill, which is located on the grounds of the Boulder Mountain Lodge, has received numerous accolades from both local and national press over the years. It draws clientele with its menu and its reputation, but finding qualified help has proved to be one of the restaurant’s biggest challenges.

“There’s not a business from a construction company to the school to the towns themselves, certainly my restaurant, that isn’t hiring right now. We have jobs aplenty,” Spalding said. “What we don’t have is residents to fill them.”

Making a life in a place like Boulder can be incredibly difficult, especially for someone accustomed to urban living. Cell phone service is spotty. Cultural options are limited, though outdoor recreation is in abundant supply. Grocery runs can require long drives to bigger towns. And while there are jobs available, many are not the kind capable of providing a steady living.

Lecia Langston, a regional economist with the Utah Department of Workforce Services, said tourism jobs tend to come and go.

“For Garfield County particularly they see a huge amount of seasonality so that during the summer they basically have to import a lot of their labor because they need it, but they don’t need it in the winter,” Langston said.

People who can’t afford to stay the winter on what they earned are forced to leave in search of other opportunities, as work in other more stable fields can prove tough to find.

“Garfield County has the highest percentage of leisure and hospitality services jobs in the state. They run about 43 percent of their total non-farm employment,” Langston said.

The result is a yo-yoing effect. In March, the most recent month for which numbers are available, the seasonally adjusted unemployment rate in Garfield County was 7.1 percent. That was the lowest it’s been since the end of the recession but it was still well above the statewide average of 3.1 percent.

“If you were to look at the raw rate in July for Garfield County it would be very, very, very low,” Langston said. Conversely, it would be much, much higher in December. “Kane County (in March) actually looks fairly low, given the fact that they do have a lot of seasonality. Their unemployment rate right now is 3.2 percent, which is comparable to the state average.”

Kanab on the cusp

Kane and Garfield Counties have much in common, making that difference in their unemployment rate very conspicuous.

“What’s interesting about Kane County is they do have a couple of unusual employers that make their employment numbers look a little bit different,” Langston said. “Kane County’s largest employer is actually Best Friends Animal Sanctuary. They show up in what we call ‘other services’ so they have a really high percentage of employment in that sector. The other thing that’s important to know about Kane County is they do have some manufacturing. Stampin’ Up was a homegrown company that started in Kane County and still has a sizable employment presence.”

That little bit of diversity helps make Kane’s economy more resilient. Kane County Office of Tourism Executive Director Camille Johnson said the addition of steady jobs has allowed for more stability and, as a result, investment in the visitor experience.

“We had Comfort Suites and Hampton Inn open up in the last year and we’ve got a La Quinta on line to open in 2018. Then I just learned of one of our local partners that’s doing an expansion,” Johnson said. “We’ve had a lot of new restaurants open up.”

The city also has geography to its advantage. Kanab sits within striking distance of Zion, Bryce Canyon, the Grand Canyon, Lake Powell and the Wave. The county is promoting Kanab as a place to base camp while visiting the whole variety of southern Utah destinations. The goal is to keep visitors in town long enough to help the local economy, rather than having them simply pass through on their way to another place.

Johnson said overcrowding in the banner locations like Zion also has Kane County pointing increasingly more visitors toward hidden gems outside of the Mighty Five.

“Because tourism is such a hot industry for us right now, we’re having a little bit of a labor force crisis and a housing crisis,” Johnson said. “With the two new hotels opening up and several restaurants, it spread our already thin labor force even thinner.”

Up in Garfield County though, the hospitality industry has grown more slowly since the creation of Grand Staircase-Escalante.

Commercial building permit papers obtained by KSL through an open records request reveal much of the new lodging construction over the last 20 years has focused Ruby’s Inn or the Bryce Canyon gateway communities. Recently, more rustic rental options like cabins, yurts or RV parks have started to open around Escalante and Tropic.

Back in Kanab, some fear the rapid growth could dilute the history and western character of the region.

“Locals will say to me ‘we don’t want to be like Moab, we don’t want to be like Springdale, please don’t let that happen’,” Johnson said. “They’re afraid that we’ll lose the spirit of our community and our heritage and then it won’t be appealing for locals to stay here and then they uproot and then we lose that heritage.”

The tale of two Utahs

The loss of locals is already happening and not just in Kanab. It’s evident from the average age in many rural Utah counties.

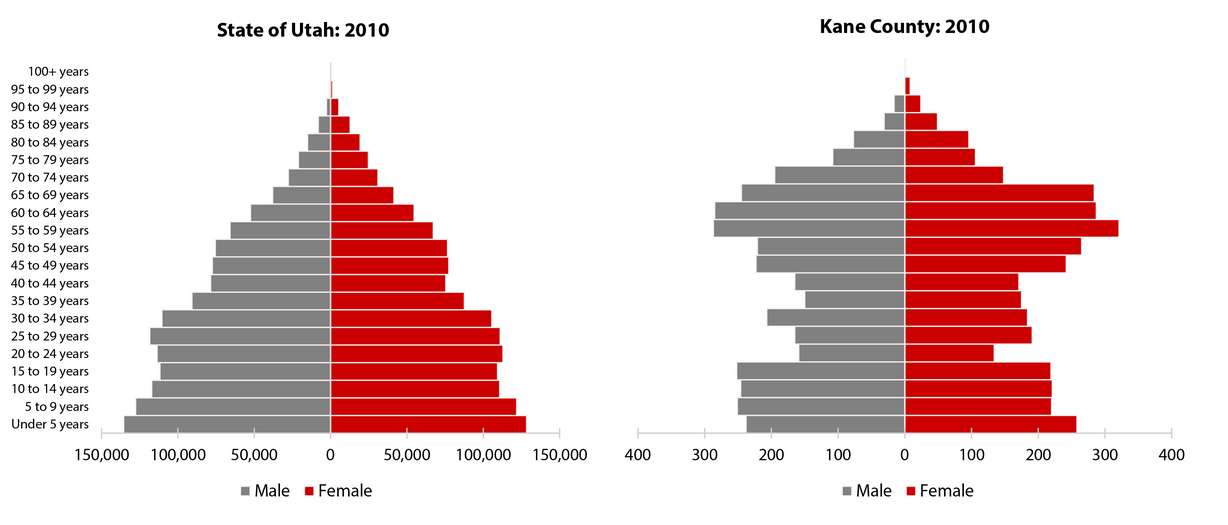

“There are two different economic realities in our state. We call it ‘the tale of two Utahs’,” Natalie Gochnour said. “They basically have children who left the counties, presumably for employment opportunities, schooling and they don’t come back. And so these counties get older and older and older.”

Why don’t they come back? Experts agree it’s a lack of high-paying skilled work in rural communities.

“It’s kind of a catch-22 because there aren’t necessarily the kinds of jobs young people want, or that pay the kind of wages that they’d really like to have, so they leave and you don’t get the population growth that you need to spur the economic growth,” Lecia Langston, the Workforce Services regional economist, said.

Garfield County even declared a state of emergency in 2015 due to declining enrollment at Escalante High School.

“In 1996 you had about 144 children enrolled at Escalante school, seventh through 12th grade,” Commissioner Leland Pollock said. “When we declared that state of emergency it was down to 51.”

Pollock points to Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument as the primary reason for the drop. Others though see the problem in more nuanced terms.

“I think it’s really a time to think very purposefully about rural Utah, particularly rural Utah that’s hurting, and figure out how do we connect and unify and help,” Gochnour said.

She suggested that could mean having policymakers lean on urban Utah’s strength, investing the fruits of Wasatch Front productivity into rural counties through infrastructure improvements like better roads or broadband access. At the same time, battles over public lands could be quieted by some good-faith deal-making.

“I think a really productive place for state decision makers to focus is on land exchanges and making all of these state institutional trust lands that are locked up inside federal lands, not accessible, getting them closer to the cities, closer to the towns and letting those towns grow,” Gochnour said.

The Wasatch Front could in turn benefit in the form of reduced air pollution and traffic congestion, as more people disperse into areas outside of the urban core. Gochnour suggested outdoor gear companies already operating in the state could lead the charge, choosing to locate their manufacturing facilities in areas like Kanab.

“Maybe it’s time for the state and the federal government, locals, recreationists to all come together and say ‘there is a path forward that can address our needs’.”