Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — The volcanic activity below Yellowstone Park is alive and well; and now it appears the upper magma reservoir underneath, which fires all the geyser attractions, is much bigger than scientists once believed.

According to University of Utah distinguished research professor Robert Smith, "This upper crustal magma body is 2 1/2 times bigger than we had thought before."

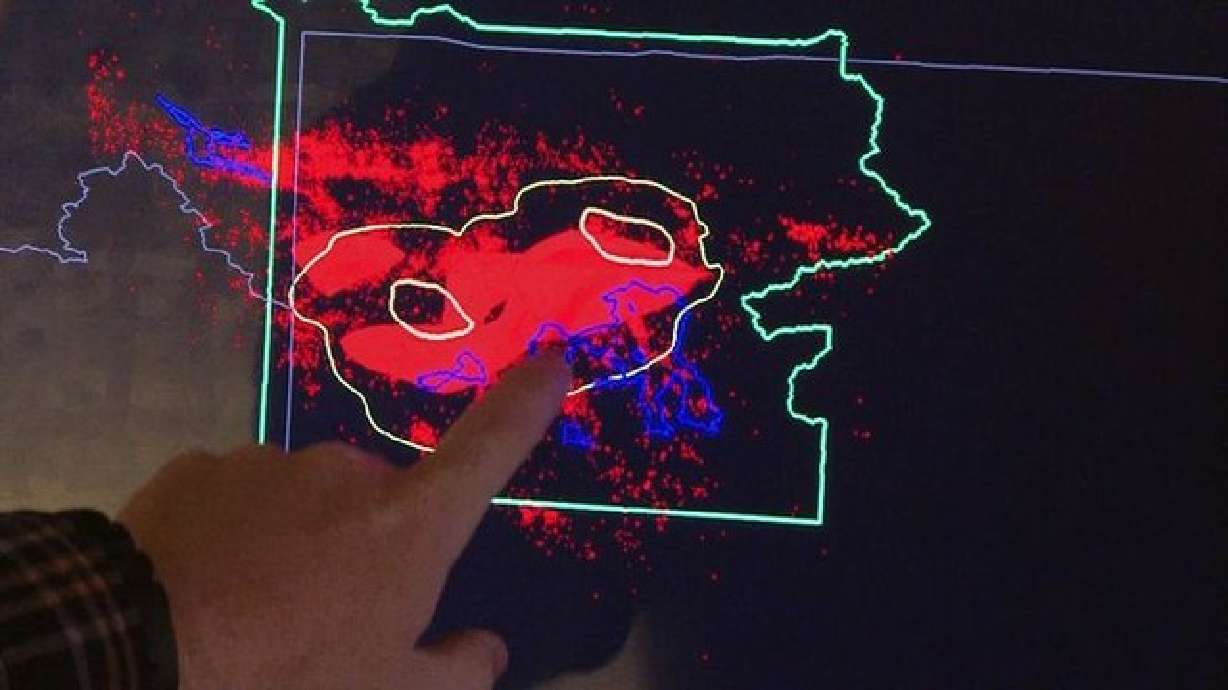

Jamie Farrell, the postdoctoral student who made the discovery, said, "Our new results show the magma reservoir is about 60 miles long from southwest to northeast."

Older imaging showed a smaller reservoir; but the newer, larger magma map extends beyond the park caldera's boundaries and close to the surface, in a remote and active area known as the Hot Springs Basin.

For the Utah research team, the discovery takes on a special significance.

"We believe that this is the largest imaged magma reservoir on the earth," Farrell said.

With the evolution of more and better instrumentation in and outside the park, Smith and Farrell say their vision of what's under the surface is simply much clearer than what scientists were able to pick up before.

Smith, who began studying Yellowstone some 50 years ago, says with each passing year — and all the postdoctoral students, geologists and geophysicists who've mapped and analyzed the infamous caldera — the data just keeps getting better.

"It's like having the lens of your eye get better and stronger, as you see more and more resolution and higher and finer detail, " Smith said.

Related:

So, does this bigger magma reservoir mean Yellowstone could blow its top as it did 640,000 years ago? Not likely, Smith said.

But if something should happen, Smith and his colleagues believe it more than likely will occur on a smaller scale.

"We've know the volcanic history of Yellowstone for the past 50 years," Smith said. There have been three giant caldera eruptions, sometimes called super eruptions; and in between, 80 to 100 inner-caldera eruptions, he said.

But now, even if the magma reservoir should become recharged at some point and make its way along nature's conduits — which in the Hot Springs Basin are only 4 miles below the surface — the smaller eruption would probably be more spectacular than devastating.

"These features are flows," Smith said. "They might be explosive locally, but they may cover only 1 or 2 square miles. They may only be a few hundred feet thick."

This kind of release of magma to the surface might happen and it might not. No one is making any predictions.

"Some people will say if you find more and more magma, it's a bigger hazard," Smith said; "but no, it really isn't."

At Yellowstone, the University of Utah serves as the park's monitoring sentry. With a network of over 35 seismic stations, scientists listen to the volcanic music — which comes in the form of earthquakes, an average of 1,000 to 2,000 a year.

Most of the earthquakes are small, but they always serve as reminders that the shifting land masses and the volcanism that feeds the wondrous park is what makes and keeps Yellowstone an adventurous living laboratory.