Estimated read time: 1-2 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK, WYO. -- Bad news for Yellowstone.

Scientists recently discovered the giant underground plume of hot rock feeding the park's so-called supervolcano is even more gigantic than originally thought -- which means if and when that volcano blows, we're in trouble.

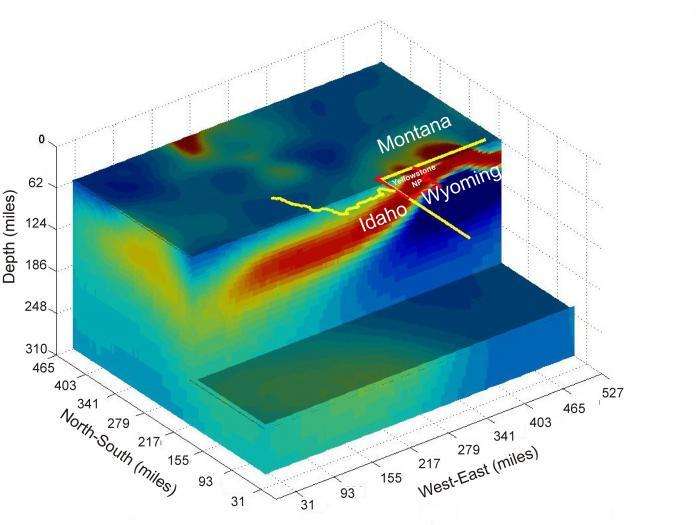

Earlier studies used earthquake waves -- the fancy term being seismic tomography -- to show the magma chamber slanted downward like a tornado at a 60-degree angle and spread 150 miles toward the Montana-Idaho border.

A report by scientists from the University of Utah reveals geophysicists tried out a new measuring technique known as magnetotelluric imaging -- which looks at the plume's electrical conductivity -- to reexamine that plume. By taking a peek from that angle, they learned it actually extends at least 400 miles -- a whopping 250 miles larger than previously assumed.

So essentially, the supervolcano -- a terrifying term in and of itself -- is getting almost three times the amount of juice. Yikes.

National Geographic interviewed study leader Michael Zhdanov -- a geophysicist with the University of Utah -- about the startling discovery. He explains the new imaging is something akin to an MRI, where the old measurement data was more like an ultrasound -- both effective forms of measurement with different advantages.

But those who live near Yellowstone don't need to run for the hills just yet. The good news is, says Zhdanov, this new discovery doesn't mean the volcano is any closer to blowing its top. Instead, the data can help scientists "build better geological models of the crust and upper mantle for mineral exploration and general understanding of geological structure."

Bottom line -- this is a hot discovery.

Email: Jessica Ivins