Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

If you live near a freeway, there's a significantly higher chance your child will get leukemia. That was the tentative conclusion of a little-noticed study by the state health department more than two years ago. Now, clean air advocates say follow-up studies and action are long overdue.

The leading suspect is benzene, which comes from vehicles and other sources such as refineries. The state study in 2006 was not meant to be definitive, but it fits a growing body of evidence that heavy traffic increases the risk of cancer for children.

State investigators mapped the homes of 465 children with leukemia. They concluded the risk is significantly higher within about 1,000 feet of freeways and busy streets. "The closer you are to freeways, the greater the potential risk. But we can't quantify that," said Sam LeFevre, environmental epidemiologist for the Utah Department of Health.

But the so-called "pilot" study in 2006 had relatively few leukemia cases and left many questions unanswered. It didn't factor in such issues as refinery pollution or the socioeconomics of people living near freeways. "You know, we don't know if these children are getting good nutrition and other kinds of factors that would help prevent leukemia," LeFevre said.

The state wanted follow-up studies but couldn't line up grant money. "We think there's a connection with benzene from auto emissions. We would like to use this study to demonstrate the need for reformulated fuels or other kinds of emission controls," LeFevre said.

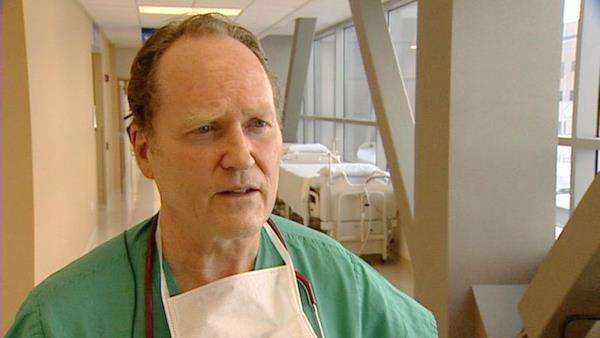

Clean air advocate Dr. Brian Moench said, "That's consistent with studies that have been done in other parts of this country, as well as in Europe."

Moench is with Utah Physicians for a Healthy Environment. He says better studies would help, but it's time for action on hazardous chemicals like benzene. "The medical data would strongly suggest that if we can reduce these kinds of emissions to our airshed, that we will have less incidence of cancer, especially among young children," he said.

Moench says waiting for better studies is dangerous. "That was a game that was played by the tobacco industry, beautifully, for 30 years. And we delayed acting on tobacco for decades after we should have. We should not make that same mistake with things like air pollution," he said.

Moench worries that any forward-thinking ideas will run into hard budget realities. The Legislature may cut funding for health and the environment, making regulatory initiatives even less likely.

E-mail: jhollenorst@ksl.com