Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

PRESTON, Idaho — A bald eagle and red-tailed hawk scream in circles above a seemingly unremarkable cattle pasture, as a late morning fog recedes from the banks of the Bear River. Just miles to the north, an ancient Lake Bonneville broke through Red Rock Pass and flooded much of southern Idaho around two millennia ago, leaving behind the silty earth below.

These lake deposits make for fertile farmland, but the nature of the soil allows water to erode the sediment relatively easily, carving channels deeper and deeper, year by year. Little Mountain remains obscured by low clouds, descending onto the steppe where a small canyon abruptly fans out to the northwest.

It was in this place where bands of Northwestern Shoshone gathered since time immemorial, returning from the salmon runs of Idaho and the big game hunting of Wyoming. The gathering site, called Mo-so-da Khani or "Home of the Lungs," was sheltered from the wind by high ridges, had easy access to water including boiling natural springs, and abundant construction materials.

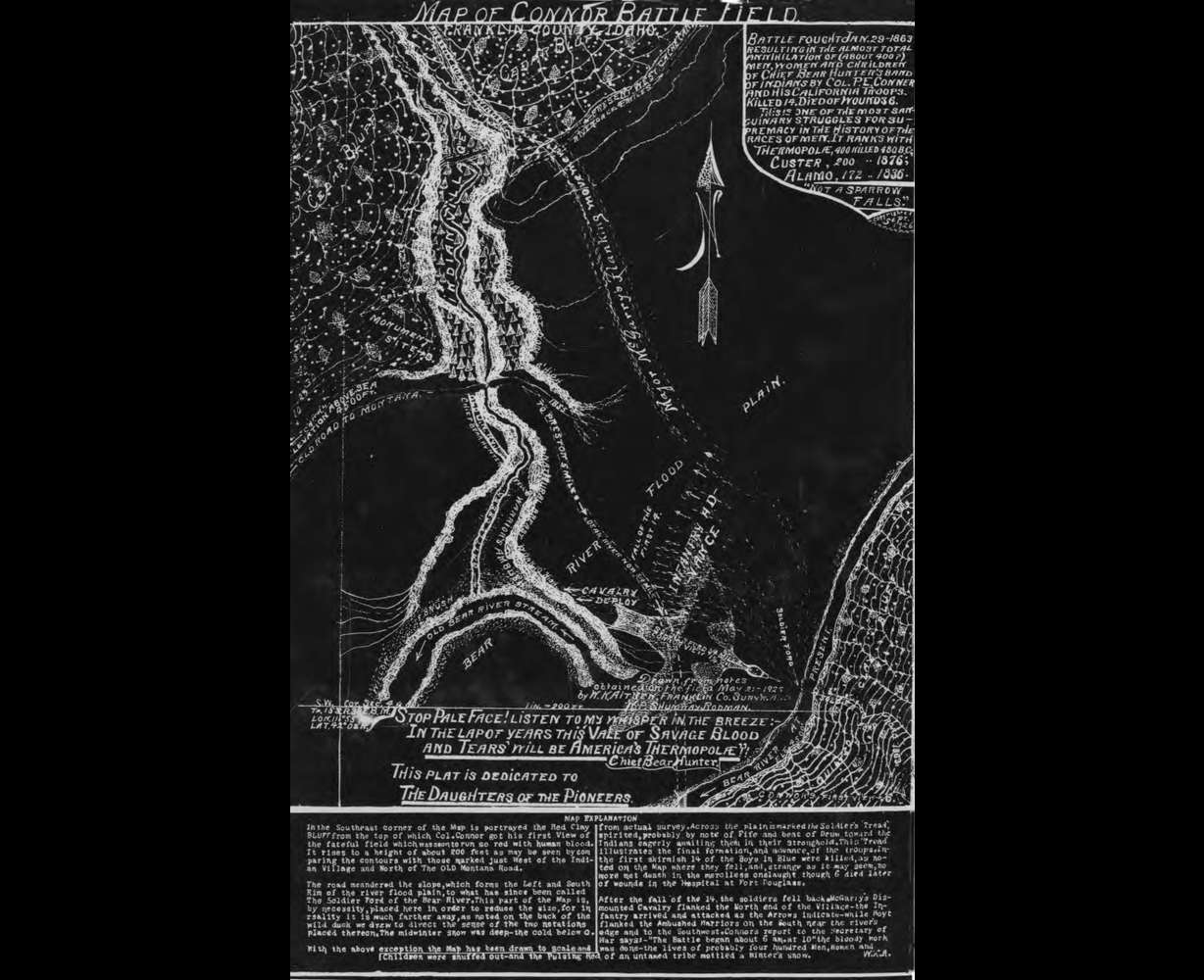

On Jan. 29, 1863, volunteer soldiers under Col. Patrick Edward Connor attacked the Shoshone wintering site. A foot of snow blanketed the valley on a day so cold that whiskey froze in the barrels. Most of the Shoshone bands' men of fighting age had recently left on a hunting expedition. Those who were left had time for one volley from black powder rifles before soldiers descended upon the group, in what became known as the Bear River Massacre, one of the single largest mass killings of Native Americans in U.S. history. Between 200 and 500 Shoshone were killed, with soldier casualties numbering 14.

This is where bullets cut through the willows like a scythe. And over there, on the bank, women hid with their babies under a beaver lodge. It broke free in the current and floated down the freezing river. Brad Parry, vice chairman of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, walked through the pasture with a group of engineers and scientists on Feb. 14, recounting the oral history.

But it's difficult to imagine, looking around at what appears to be a simple plot of flattened grazing land, dotted with cow pies and trampled straw.

Battle Creek, which is now piped in a straight run along the two-lane U.S. 91, used to fan out from the mouth of the canyon, creating a wetland where the group stands now. The clear-cut fields used to be dense with willows, bulrush, sedges and cottonwoods, full of beaver dams and migratory birds. The canal has been choked with invasive, water-hungry Russian olive trees and phragmites.

This degradation of the creek has taken a toll. Without the natural filtration processes in place, Battle Creek projects a massive plume of sediment laden with phosphorus which clouds the Bear River's current.

Since the Shoshone were violently cast from their wintering site, the habitat along the Bear River and the creeks that feed it have become severely degraded due to agricultural production, Parry says. The Great Salt Lake's largest tributary is now listed as an impaired waterbody under the Clean Water Act.

More than 75% of Idaho's wildlife relies on these wetland areas, an Idaho Department of Fish and Game report says, which make up only 3% of its landmass. In Utah, the difference is even more stark — 0.5% of the state's wetlands support 80% of the state's wildlife at some point in their life, according to the Utah Department of Natural Resources.

In January 2018, the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone purchased over 500 acres around the massacre site, and is in the process of acquiring the rest of the traditional wintering area. It was the first time the tribe regained ownership and access to this ancestral land. Now, it is using historic aerial photography and written accounts of the site conditions to develop vegetation restoration goals and mimic pre-1863 conditions as closely as possible.

The tribe, along with Hansen, Allen & Luce engineers, Bio-West, Allred Restoration and Utah State University began the design, planning and feasibility work for stream restoration structures along the Battle Creek Tributary in 2019. Finally, this March, the team is set to break ground on the construction phase. This work involves building diversion structures, beaver dam analogs and box culverts. New flow paths will also be constructed, resembling the natural branching "braids" of the historic wetland, which will require additional bank stabilization.

"It's really a dream project," said Bio-West wetland scientist Bob Thomas.

The proposed project has grown significantly in scope, from an initial goal of removing invasive species stabilizing banks to the new vision of completely replacing the ditch along the highway with a meandering creek, constructing a fish-passable diversion structure for flooding, and installing beaver dam analogs.

It's also being used as an occasion to measure the impacts at every phase of the work, metering water levels and quality along the creek. "We've had several of the upstream farmers see our equipment and how we're measuring the water, and they're like, 'Could you guys come help us?'" says Brian Andrew, the lead project engineer.

According to Parry's project grant application, the "restoration of an active floodplain, including beaver dams and wetland marsh habitats will be a huge sink for sediment and nutrients, significantly reducing turbidity, sediment, and nutrient loads and along with increased flows and lower water temperatures, the project will improve overall water quality in Battle Creek and in Bear River."

The hope is that, one day, they will be able to reintroduce the Bonneville cutthroat trout to Battle Creek.

"There's really a watershed approach to what we do here," said Tyler Allred, a geomorphologist for Allred Restoration. "Not only can we increase the amount of water, it can be cleaner."

Some work has already been done to remove Russian olive trees and other invasive species from the banks of the creek. In August 2021, the Utah Nature Conservancy donated $25,000 to the project, paying for the Utah Conservation Corps from Utah State University to come in and remove around 5 acres of these plants from the Upper Battle Creek north tributary.

The ultimate goal is to remove a total of 15 acres worth of trees from the land. The Mountain Studies Institute says one Russian olive tree pulls about 75 gallons of water a day. In Parry's estimation, the tribe will be sending about 13,000 additional acre-feet of water to the Great Salt Lake every year. Andrew said that's a conservative estimate, and using different methods, that number increases significantly.

"When people hear that, they say, 'It's like you guys are creating water.'" Parry said. "Well, no, we're just not losing the water."

These benefits are coming because of what the tribe wants to do with this land, which is restore it. They haven't said, 'Let's figure out how to get more water to the Great Salt Lake.' It's a benefit that comes from managing the land in a good way.

– Tyler Allred, geomorphologist for Allred Restoration

"A lot of us have done restoration for our careers, primarily. These benefits are coming because of what the tribe wants to do with this land, which is restore it," Allred said. "They haven't said, 'Let's figure out how to get more water to the Great Salt Lake.' It's a benefit that comes from managing the land in a good way."

While the team acknowledges the importance of farming in the area, "An enormous amount of our water gets used for agriculture for extremely low-value crops," Allred said. "And it's maybe not the highest and best use. The tribe recognizes that."

With the help of 400 volunteers, about 10,000 native plantings have been placed along the banks. By the end of it, Darren Olsen, Bio-West's senior hydrologist, hopes to have 200,000 plantings representing hundreds of different species, which have been collected along the creek and grown by a local plant nursery.

Trout Unlimited, the Bear River Environmental Coordination Committee, Utah State University and the Sageland Collaborative provide funds and expertise to the project. The team wants this project to be a proof of concept, using the land management principles of the tribe as a way to improve the quality of watersheds across Idaho and Utah, improving drought resistance and allowing a larger amount of cleaner water to flow south.

Education is another large goal of the project, with the tribe raising funds and seeking donations for the Boa Ogoi Cultural & Interpretive Center, to educate as well as preserve the history and knowledge of the Northwestern Shoshone Band, which would be built on an overlook to the west, above the hot springs.

"We didn't set out to save the Great Salt Lake, we set out to be better stewards," said Parry, "and it just happens to align."