Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SOUTH JORDAN — For Kathryn and Paul England, a journey through the Wizarding World of Harry Potter began as magic.

"We were on our dream vacation," Kathryn England said of their trip last fall.

But even in Orlando, dreams can become nightmares. Her nightmare unfolded with a call she took while in the Universal Studios Florida park. The caller said he was from the "fraud department" of Chase Bank – her bank. Someone had wired $20,000 out of her account, he said. And it wasn't her.

"I said, 'We have to get this back,'" she remembered. "He said, 'That's what we're going to do and help you.'"

Help meant going into her Chase app and following his directions to a tee.

"The guy kept telling me over and over again, 'This is the only way to get your money back,'" she said.

An impostor revealed

The guy did his homework. She says she did not give him any personal or banking info. But during two hours of button tapping, she received several passcodes. And as instructed, she read them back to the caller. Finally, he told her to delete the Chase app from her phone and wait for a callback.

"An hour went by. Two hours went by. I said, 'Something is so not right,'" she said. "So, we went back to the hotel and called Chase."

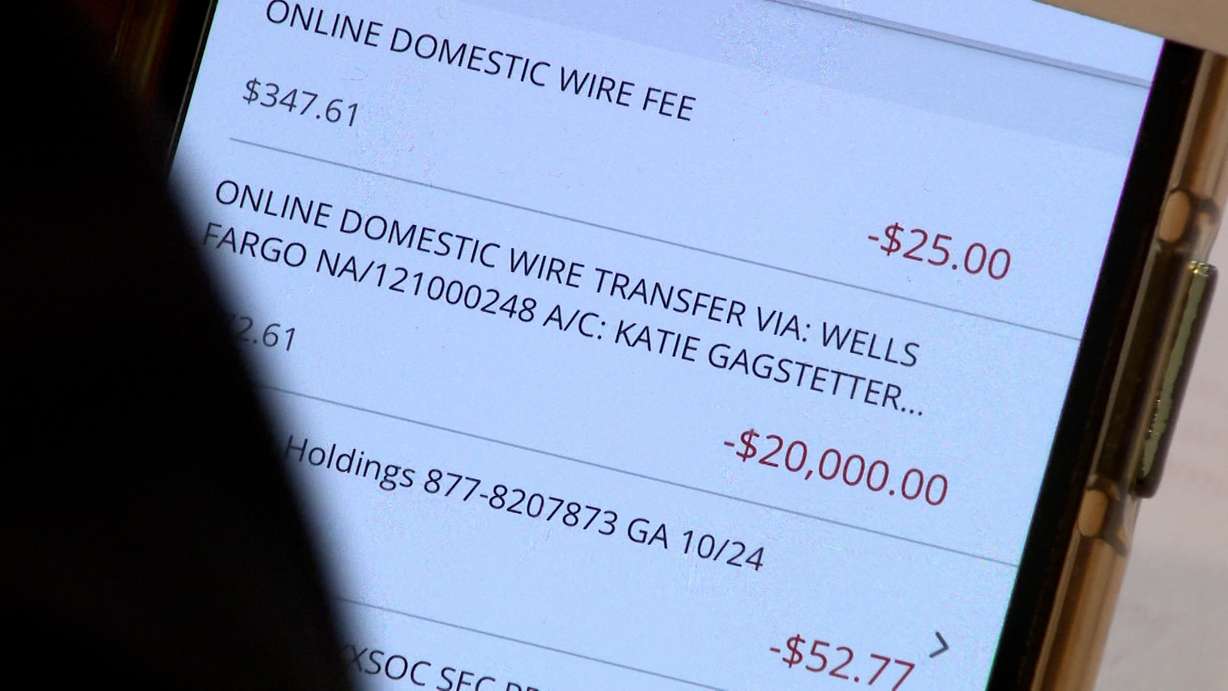

That call revealed real gut-punching news: She didn't recover that $20,000. Instead, she had been duped by a scammer who then really wired all that money from her account to an entirely different bank.

"I couldn't talk about it without crying," she said. "This money was actually earmarked for some pretty important things."

What is worse, she says, is that Chase denied her claim to be reimbursed for her loss, saying it determined she either benefited from the transaction or she authorized it.

"It was done on wire that he had me push the buttons," she said.

Loopholes in federal banking law

Because it was Kathryn England who actually pushed those buttons, she lost her protection under a loophole in the Electronic Fund Transfer Act. That federal banking law only covers unauthorized charges, such as someone stealing your debit card or a hacker breaking into your online account. But it will not protect people tricked into sending money.

"It just impacts everyone, and they're heartbreaking stories because there really are no protections," said Carla Sanchez-Adams, senior attorney with the National Consumer Law Center.

She says even if you are duped into clicking the send payment button, it is considered authorized under the Electronic Fund Transfer Act.

"Technically, the way that the law is written is, if you authorize it, if you initiate it, then it's not unauthorized and there's nothing that you can do," she explained. "You wouldn't have protections in those scenarios where people are tricked into sending money and it turns out to be a scam because you hit push the send payment, right? So, if you did it, then under current law, that is not unauthorized — you actually authorized it."

Wire transfers not covered

And wire transfers are not protected under that law, period. That's become a huge problem since the pandemic, says Sanchez-Adams.

"What happened after 2020 in the pandemic is that wire transfers are now available through digital banking," she said. "Whereas before you used to have to go in person into a branch to initiate large transfers through wire. And now, you know, you can set that up and do it online."

Her group argues decades-old banking laws should be updated to reflect evolving scams. She says they're pushing for protections for folks tricked into sending money and for wire transfers.

So, what does Chase have to say about what happened to England? In a statement to the KSL Investigators, it said, "It's heartbreaking when criminals trick consumers into sending money or sharing their account information, passwords or one-time passcodes. Banks will never ask for this type of information, but scammers will."

Protecting your money from fraudsters

That still leaves England out $20,000 – and an extremely expensive lesson learned: If your bank's fraud department calls you, hang up and call the number on the back of your debit card.

"That way you will know that you're getting the real bank, instead of a really, really good fraudster who got me," she said.

You should also never share any banking info or passcodes with anyone who is calling you or texting you. Don't click any links in texts or emails. And if you've been hit, report it immediately to your bank, your police department, the FBI, and the Federal Trade Commission. Getting your money back will be an uphill battle, but the quicker you act, the stronger the odds of getting back at least some of it.

"I often recommend, if there's complex cases, to consult lawyers because there may be ways that a bank could be on the hook," said Sanchez-Adams. "There may be some negligence, some knowledge on the part of the bank."