Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

PROVO — David Long was a professor at Brigham Young University in 1999, using a satellite remote sensor to study sea ice, tropical forests and icebergs — when he and his students accidentally stumbled upon a lost iceberg.

"I had to call the National Ice Center to find the name of this iceberg. ... After a while, they came back and said, 'Oh, this is iceberg B10A, which is an iceberg that we were tracking and we lost track of it four months ago. You found it — it's in a shipping lane," Long, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, recounted.

He then began providing the center with all the iceberg tracking data he could find, using his scatterometer.

"That's how we got started in icebergs, and since that time, we've continued to maintain our iceberg database," Long said. "It was sort of serendipitous."

The iceberg he and his students discovered was bigger than the Utah Valley. The chunk of ice would stretch from Nephi to Bountiful, measuring 60 miles long and 20 miles wide.

Now, 24 years later, Long was part of a study comparing current observations of large Antarctic icebergs with explorer observations in the 1700s, using modern satellite datasets, showing the massive icebergs are found in the same areas they were pinpointed in three centuries ago.

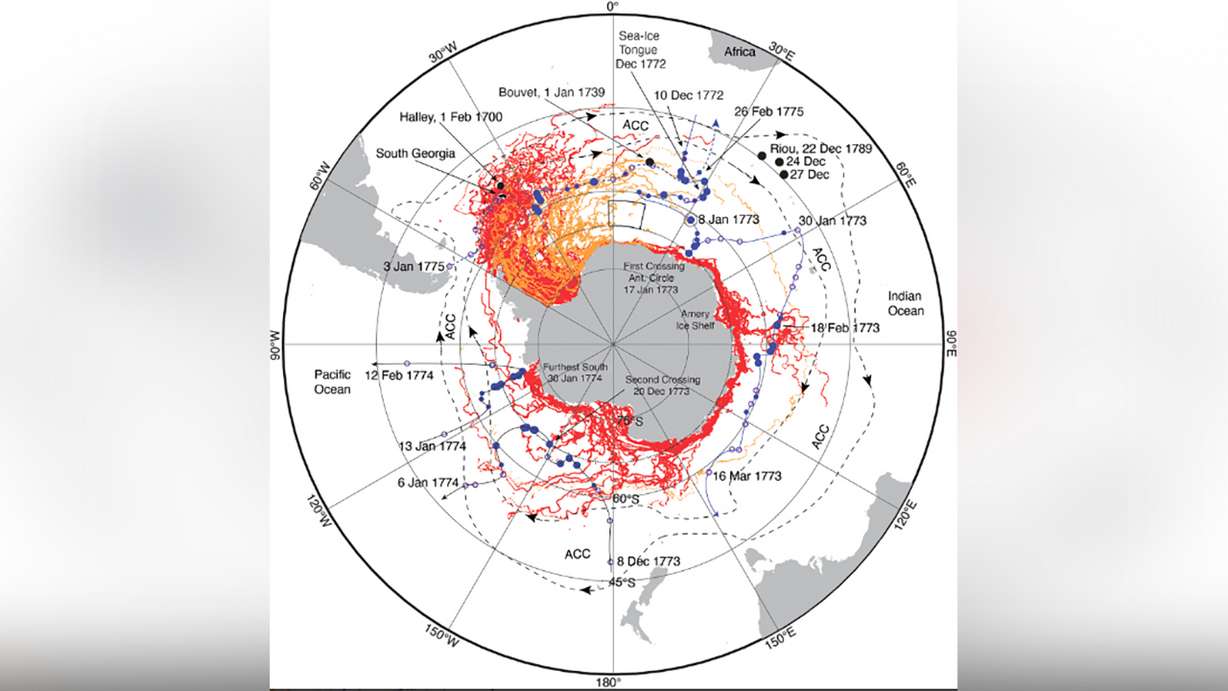

Using primarily the journal records of Captain James Cook's 1772-1775 Antarctic circumnavigation on the HMS Resolution — in which he noted the positions of hundreds of icebergs — Long, along with researchers from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory and the University of Washington's School of Oceanography made comparisons with the two largest modern data sets available today: the BYU/National Ice Center and Denmark's Alfred Wegener Institute data sets.

"In reality, this is more of a human interest story than it is an important scientific result," Long said.

The team's recent discoveries showed that despite the outdated and rough methods used by 1700-era explorers, those explorers were able to accurately determine the location of icebergs; and iceberg movement patterns have behaved consistently for more than 300 years.

They aren't the same exact icebergs observed three centuries ago, Long said, but they are breaking off from glaciers and moving through the ocean in similar patterns as they were in the 1700s.

Seelye Martin, Long's co-author in the study, extracted Cook's iceberg observations from a line-by-line search of Cook's journal-turned-book about his journey: "A Voyage Towards the South Pole, and Round the World."

Martin, Long and another co-author, Michael Schodlok, then compared the positions of the icebergs noted in Cook's journals of the iceberg plume east of Antarctica's Amery Ice Shelf — along with iceberg distributions in the Weddell, Ross and Amundsen seas — with modern data.

"We found that they're generally in agreement, which is good, because that sort of (shows) that icebergs today are not so different from ones back then, 300 years ago," Long said. "We added those together, and that's when the cloud of points kind of matched up between what these old explorers saw and what we see now."

Long, a noted fan of puns around BYU's campus, said that he likes to use the word "cool" when describing the feeling his team had when they realized the data sets were in agreement, noting that his description is "kind of redundant when talking about icebergs."

"Scientists are mostly working, kind of, on hard work, and a lot of what I do is kind of tedious and boring — looking at these pictures, identify the icebergs and track where they are and go to the next picture," Long said. "When you get to see it apply and in comparison to something like this, it's really kind of fun."

Long's biggest takeaway from his research endeavor?

"You never know when your journal will be useful," he said, referring to Cook's records.

"He was recording something that was kind of trivial in his mind — seeing some ice in the water. Once you've seen it once or twice, it's like, 'Eh, I don't need to write that down,' but he kept doing it and because he did that, we have this data and it was valuable," Long said. "Who could've thought that something that somebody wrote 300 years ago would still be useful today, 300 years later?"

The research was published last month in the Cambridge University Press Journal of Glaciology.