Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

MURRAY — The Beijing Olympics officially began Friday with the opening ceremonies, but preparation has been years in the making.

The U.S. Ski and Snowboard team has partnered with Intermountain Healthcare's sports science lab at the Orthopedic Specialty Hospital, to give our athletes a competitive advantage as they train in Utah.

Hannah Soar, 22, is making her Olympic debut this year as a U.S. women's mogul skier.

"I feel like that's just so cool, you know when you finally get to realize the moment that you've been dreaming of for like your whole life at this point," she said.

Soar grew up skiing in Killington, Vermont, but has competed and trained in Park City ever since she made the U.S. Ski Team when she was a junior in high school.

"My love for skiing definitely came from my parents and my grandfather was also really into skiing," she said. "It kind of was just instilled in me at a young age, the classic started-skiing-at-18-months story."

In the fall of 2018, she suffered a severe ankle injury, two weeks before her first World Cup competition. Though she had mostly recovered a few months later, Soar said her left leg was still 30% weaker than her right despite doing the same exercises on both legs.

"I had a lot of lingering pain there, a little instability, and stiffness," she said. That's when she started training at Intermountain'a Spots Science Lab, in Murray.

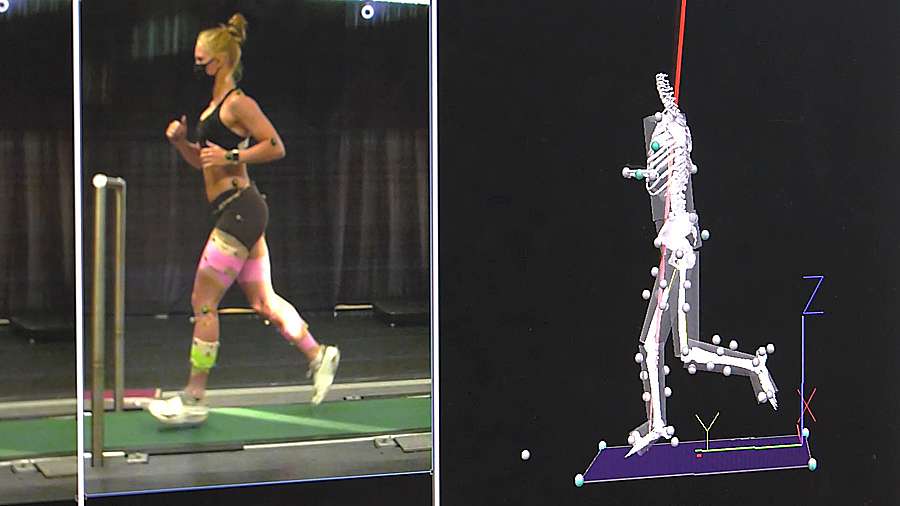

"They put a lot of motion sensors on you and then you kind of look like a skeleton on the TV," she explained. "It became pretty obvious that due to not wanting to take the load in the ankle, I was just using different joints."

Intermountain clinical biomechanist Bill McDermott said the lab analyzes data to pinpoint an athlete's weak spots and deficits. "Those are tracked in real-time in three dimensions down to a millimeter of movement at a really fast rate, so up to 300 frames per second," he said.

The computer software builds a 3D model of the athlete. "That allows us to get down into the details of how they're moving. We don't even need to know what her injury background is. We can look at her as a whole and start breaking it down into finer points," McDermott said. "The motion capture will tell us if she's moving that ankle correctly, or is she compensating at the knee or hip or other leg."

In addition to the reflective sensors, McDermott said they use a state-of-the-art treadmill that measures the force the athlete is putting into the ground. "We can actually calculate at her ankle, her knee, and her hip, how the muscles are producing force (and) power," he said. Then the trainer coaches the athlete through individualized exercises based on the data they've gathered.

"The people at TOSH can dissect the data. They talk with my strength coach, Josh Bullock, and the two of them create a good program for me that's very specific and useful," Soar explained. "For example, with my ankle, I realized I was losing a bit of arch support, so I had to start grasping marbles with my toes and like folding my arch, you know, little things like that."

McDermott said this program not only helps athletes recover but can also help prevent future injuries. "Those compensations actually are linked to a higher risk of reinjuring the area of the joint that they just are rehabbing," he said.

"Pounding moguls every day and landing jumps — like it's hard to not feel pain if you do have an injury somewhere. It's a lot of force," Soar said. "So, it enabled me to have less pain when I was skiing. But I was able to get my left leg strength back up to where it should be," Soar said, adding that it's brought her to the top of her game.

"At that level, it only takes a little bit more improvement to separate you from the other athletes," McDermott said.

Soar said she's ready to compete.

"I feel really good right now so now I can just think about getting medals," she said.

She's grateful she has the chance to compete in the first place, especially during a pandemic. "Yes, it's a lot of hard work, but it's also a lot of luck at the same time and I think I'm just trying to bask in the moment of like, 'Wow, like, everything came together,'" Soar said.

The program isn't just designed for high-performance athletes. Any orthopedic patients recovering from a knee, hip, or ankle injury, or surgery, or even a total joint replacement can participate, in addition to other local athletes, like high school sporting teams.