Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — A new study of gas emissions in eastern Utah yielded a surprising result that could change the discussion of methane reduction at a time that global leaders have begun to focus more on the greenhouse gas's role in climate change.

The study led by University of Utah researchers found gas emissions within Utah's Uinta Basin were cut in half during a six-year period ending in 2020, as oil and gas production slowed down. They also found methane-leaking oil and gas wells remained about the same during that six-year span despite the drop in oil and gas production, which countered previous research suggesting it would increase.

The second finding, they wrote, may have been influenced by voluntary measures to cap oil and gas wells once they were abandoned. The researchers' findings were published in Scientific Reports Tuesday.

"Our work in the Uinta Basin shows that the methane emissions can change over multiple years and it is important to bring a long-term perspective and monitor these emissions over multiple years as well," John Lin, a professor at the University of Utah Department of Atmospheric Sciences and the study's co-author, said in a statement.

There's a reason that climate scientists are concerned about methane, which can be leaked into the air during fossil fuel production. Per University of Utah researchers, the greenhouse gas methane is believed to have about 85 times more global warming potential in the first 20 years it is introduced into Earth's atmosphere than carbon dioxide.

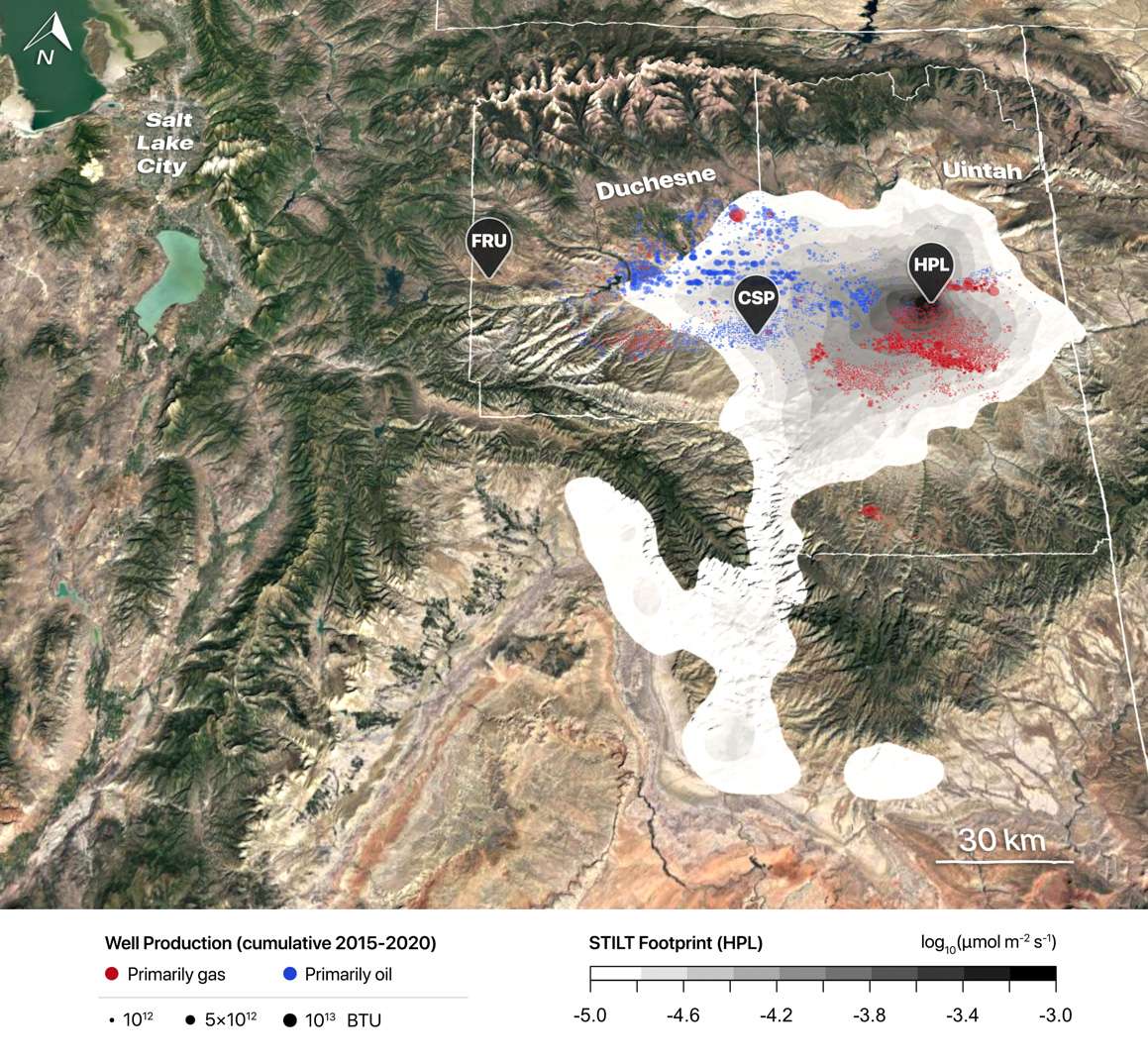

So the team of researchers from the U., Utah State and West Texas A&M University began collecting data in 2015 after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration provided the project funding for the first of three sensors. There are about 10,000 oil and gas wells located in the area, the researchers pointed out in the study.

Interestingly enough, the oil and gas market changed over the time the team began collecting data. As oil prices dropped, so did oil and gas production in the Uinta Basin. Researchers found that methane emissions as a result of production in the Uinta Basin nearly fell by half between 2015 and 2020 as natural gas production declined at about the same rate.

But the biggest surprise came from the methane leakage rate. They found that about 6% to 8% of produced natural gas leaked into the atmosphere in 2020 — a statistic that remained constant throughout the six years of data collecting even as gas production dropped. While the rate was still much higher than the national average of about 2%, the finding countered past studies that have suggested wells that produce less natural gas would leak a higher proportion of methane.

Researchers wrote that the percentage was likely high as a result of the "abundance of low-producing wells" in the region, but they weren't entirely sure what caused the rate to remain constant instead of increase. Changes enacted by the Environmental Protection Agency over the past decade would not have taken into account the wells they studied in the Uinta Basin.

They believe that "voluntary measures by some industry players" may have influenced some of the results.

"Surveys of a few companies operating in the Uinta Basin have revealed one instance of a company voluntarily installing equipment and carrying out leak detection/repair, resulting in fewer detected emission plumes," they wrote. "How widespread these voluntary measures were adopted by other companies remains unknown."

The results, Lin explained, suggest that methane emissions drop as gas production does, but improved leak detection and repair technologies can help reduce methane emissions even if production increases again in the future.

But Seth Lyman, director of the Bingham Research Center at Utah State University's Uintah Basin campus and a co-author of the new study, added it will "depend on decisions made by individual companies as well as on changes that have occurred or that may occur in the regulatory landscape" for that happen.

"The earth has only one atmosphere, and emissions in one area can impact air quality and climate across the globe," he said in a statement. "Oil and natural gas facilities are not evenly distributed around the state or around the world, but climate impacts from fossil fuels are not dependent on the location of emissions."

The study was published at an opportune time because methane has risen to the top of climate concerns. The United Nations Climate Change Conference, or COP26, which wrapped up last week, focused heavily on curbing all sorts of greenhouse gases, such as methane. Reuters reported last week that the United States and China agreed on a deal that, among other things, calls for a cut in methane emissions.

The infrastructure bill that President Joe Biden signed Monday also included nearly $5 billion to close off abandoned oil wells across the country. That is something the study suggests is important in reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Leak detection and repair can "potentially yield air quality benefits," the authors wrote, adding that there's an "urgent need" for long-term methane observations to be established, as well.

"Natural gas is likely to continue serving a key role in the global energy mix over the next several decades even under decarbonization plans. Thus, reductions in the leakage rate are necessary in order to decrease fugitive (methane) emissions without a simultaneous need to lower natural gas production," the researchers wrote in the study. "Given the White House goal of reducing the U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 50% to 52% below its 2005 emissions levels by 2030, addressing methane leaks is a measure that warrants immediate consideration."