Estimated read time: 10-11 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — We found out we were pregnant during the beginning months of the COVID-19 pandemic, during the height of the shortage of baby formula as people prepped for the worst.

At that point, most people were working from home, which meant breastfeeding mothers didn't have to use their stored surplus milk to feed their babies in child care. More people also turned toward breastfeeding as a more consistent option than formula, especially when there were times the shelves were bare.

There was more breast milk available, but many potential donors were concerned about doing the required bloodwork screening or dropping off their donations at hospitals, where patients were being treated for COVID-19.

A study recently published in Maternal & Child Nutrition showed that, over time, some milk banks and hospitals were able to communicate that there were safe ways to drop off milk curbside — and the breast milk stores that built up during those months flooded in. However, according to the study, some still haven't recovered from this shortage and are asking for more donations so they can have enough for babies in neonatal intensive care units and for babies separated from COVID-19 positive mothers after birth.

Then there were people like me, with an abundance of milk they didn't know what to do with.

No room in the freezer

My whole life I have been more afraid of breastfeeding than I was of giving birth. I had heard the horror stories: cracked and bleeding nipples, mastitis, blocked ducts, thrush, supply problems, among others.

After my son, James, was born in January 2021, I struggled to feed him. My milk wouldn't come in. I also had a cesarean section, so I had trouble holding him in a way that wouldn't hurt my incision. I saw lactation specialists and consulted the local La Leche League and joined Facebook support groups. I bought ointments and ice packs and cabbage leaves and shields. I ate lactation cookies and oats. I watched video after video explaining how to latch.

And after everything, I had multiple infections, I was blistered and bleeding, and I still wasn't producing enough colostrum and had to resort to formula. Add the sleep deprivation and I felt utterly defeated.

This struggle with breastfeeding, combined with postpartum depression and anxiety, sent me into a tailspin. I wasn't sure if I was going to be able to keep going with breastfeeding. I started exclusively pumping and then gradually added nursing back in.

Breastfeeding got a lot easier with time, and I began to appreciate the biological miracle of it all. My body has grown a whole human, and now it was using my baby's saliva to figure out what he needed and provide the custom combination of vitamins and calories and fats he required. It was like waking up with an uncomfortable superpower.

And like most superheroes in their origin stories, I had to figure out how to control it. I soon ran into another problem: oversupply.

My family has always told me I'm an overachiever, and I guess my body listened because it produced an ongoing avalanche of hormones while pregnant and nursing. I fed my baby and then still pumped an extra 40 ounces per day.

For many people who are breastfeeding, this sounds like a dream. For me, it meant pain and discomfort and never being able to sleep. I got infections that led to blisters that led to blocked ducts that led to mastitis. Again and again and again.

Our freezer started to fill up with frozen milk, and we had to buy a separate one. At first I built up a supply for when I ultimately had to go back to work, but then I started producing hundreds of ounces of extra milk aside from what I needed for my own baby.

I was drowning in milk and unsure of what my options were. I looked into local milk banks, but I wasn't sure if I would be allowed to donate because I was taking an antidepressant. Milk in milk banks is largely used for premature babies or babies in need of special care, and the application process to become a donor is strict so as not to endanger the babies' lives, or normal development.

I found some local mothers who could use breast milk and offered some of mine. That didn't quite pan out, so I looked into other options. I was bewildered to find out there are body builders who pay top dollar for breast milk to build muscle. I learned you can sell your milk on eBay. All of that didn't appeal to me. I had worked hard to make this magical milk, and I didn't want it to go to strangers on the internet for an unconfirmed purpose.

Despite my previous discouragement, I decided that I wanted to help babies in the neonatal intensive care unit, if possible. My husband and I both had nephews in the NICU, and I saw the toll that it takes on the parents, as well as the babies. I was determined to help relieve any of that stress and pain that I could, so I applied at Mountain West Mother's Milk Bank and was thrilled to find out that I qualified to donate.

What does it take to donate?

Each milk bank or donation organization has its own set of requirements. I chose to donate through the Salt Lake City-based nonprofit Mountain West Mothers' Milk Bank, which has donor collection sites throughout Utah and neighboring states. The organization is sponsored by Intermountain Healthcare and University of Utah Health and is accredited by the Human Milk Banking Association of North America.

When I reached out, I was connected with a volunteer who walked me through every step of donation and clarified that I met every requirement.

Before I was cleared to donate, I had to fill out a large amount of paperwork listing every single medicine I had taken since just before I gave birth. I had to talk about whether I smoked or drank any caffeine or alcohol. I had to talk about my lifestyle and give an extensive medical history. The milk bank called my OBGYN to confirm the medicines I was on. They called my pediatrician to make sure my baby was getting everything he needed to grow.

Then I was sent a kit for bloodwork in the mail, and I took it to a local lab. They tested my blood for any kinds of sexually transmitted infections or other issues that could be dangerous for immunocompromised babies.

When I found out that I officially qualified, I danced around my living room. It felt like all of those hours attached to a pump, feeling like a dairy cow had finally paid off. I was going to be able to help people.

I was able to donate close to 900 ounces with hundreds left over for my son from when I was on medicine for my mastitis infections.

I was privileged enough to be with a partner who supported me in this. I had access to a breast pump for free through my insurance. I had the food and drink to produce nutrient-rich milk. I could work from home and had a job that allowed me to take pump breaks. I had a place to store and freeze the milk. And most of all, I had the privilege of seeing my baby — who had lost a fair amount of weight during the first weeks of his life — get chubby cheeks and wrist rolls. He was thriving, and I wanted to use my privilege to offer other babies the chance to thrive, too.

What happens to the milk after donation?

The breast milk needs to be frozen immediately after expression, and it needs to be produced within the past nine months. After I delivered milk to a collection site using a cooler to make sure the milk stays frozen, it is sent to the Mountain West Mothers' Milk Bank to be thawed, tested and pasteurized to make sure it is safe for at-risk babies. The milk is then safely distributed to hospitals and homes throughout Utah and surrounding states.

In 2020, Mountain West Mother's Milk Bank provided 176,000 ounces of breast milk to babies in need.

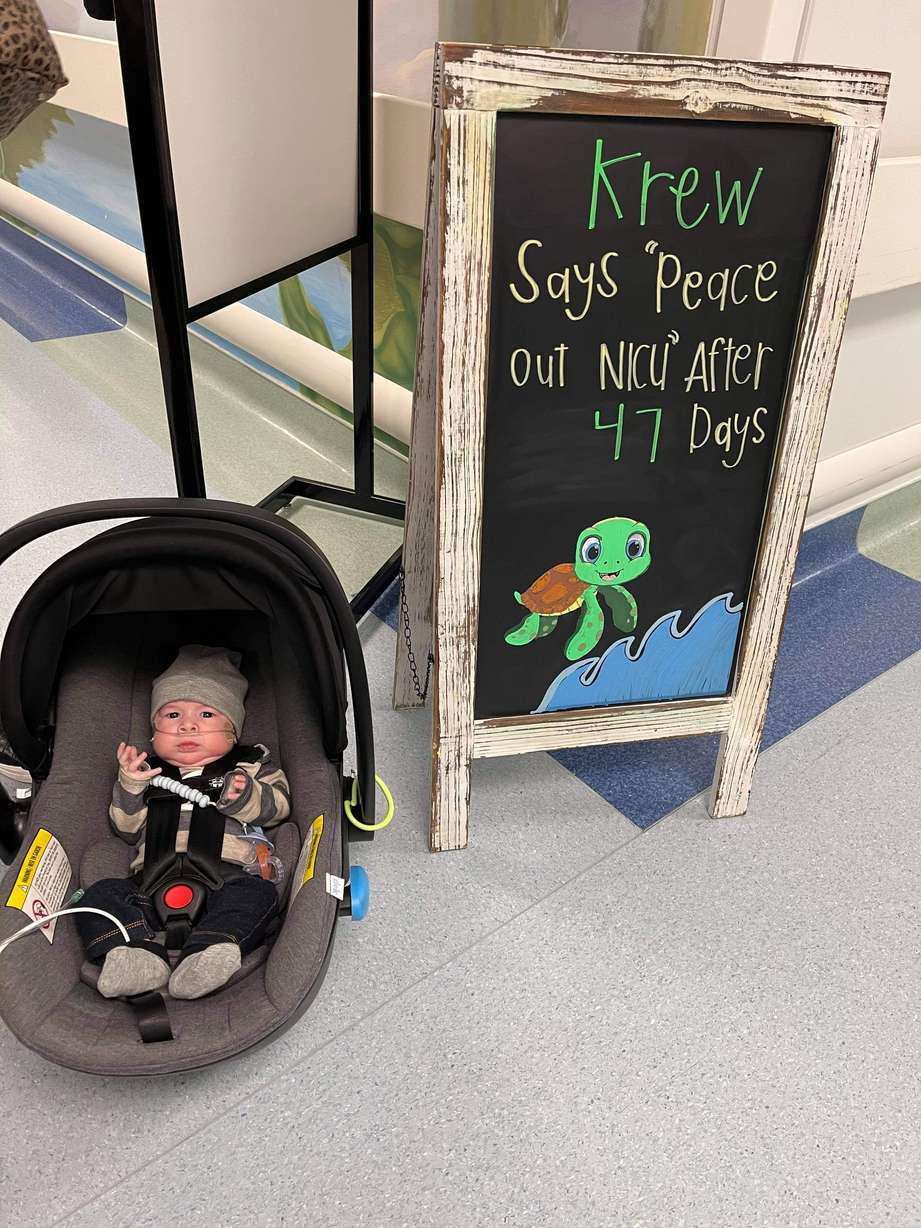

Nicole and Krew's story

Nicole Weick, 21, gave birth to a baby boy in February 2021, about two weeks after I had mine. Little Krew was born with a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, a condition in which the diaphragm does not fully close during development, allowing internal organs to push through. This can result in issues with the development of the baby's lungs, heart, liver, intestines and nervous system. Treatment is available, but the condition's cause is unknown. Many babies with severe cases do not survive.

Even though she found out about this condition during pregnancy, nothing could have prepared her for the trauma of this kind of birth. After her C-section, Weick was separated from her baby so he could receive the medical attention he needed. He went into surgery two days after birth and was intubated with a peripherally inserted central catheter for 12 days.

Weick pumped every two hours to keep up her supply, spoke with lactation consultants, hand expressed, ate and drank enough and did all she could to get colostrum for her baby. But her body was so shaken from the C-section and the pain meds that she only produced a few ounces over the first five days.

Fortunately, after the first couple days in the NICU, Krew had been transferred to Primary Children's Hospital in Salt Lake City, which offered a store of donated breast milk.

Weick produced a quarter of the amount of milk her son needed, and the rest was provided by the milk bank.

Krew was in the NICU for 47 days. Weick knew that breast milk is able to pass on antibodies so babies can better fight off infection.

"He had like 20 lines coming out of him at one time and was vulnerable to infection, so that first golden hour of colostrum is so important. It's incredible they were able to give him donated breast milk," she said.

She kept pumping day in and day out, but knew that her low supply would be supplemented so Krew could get what he needed when he needed it the most.

When he was cleared to leave the NICU after a month and a half, Weick switched him to formula because she knew she wouldn't be able to feed him enough.

Krew is now 5 months old, the same age as my son. He is still on oxygen, but he no longer has an nasogastric tube and is doing well. His mother is his full-time caretaker.

She explained that a lot of people are discouraged by the lengthy screening process for donating breast milk to milk banks and hospitals, even to the point of stigmatization, but she says getting the milk to babies who need it is "100% worth it."

She will always be grateful for the people who donated and helped take some of the stress off of her, and she encourages more people to donate if they can.

"Think about the sick babies in the hospital and the moms who struggle and cry and wish they could get their baby breast milk," Weick said. "It is priceless for me to have been able to get the donor milk because I didn't have anybody else to get it from."