Estimated read time: 9-10 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.

SALT LAKE CITY — Growth is an issue that's been on the minds of Utah leaders for some time now. Ask anyone who oversees planning in the state and they'll likely say that the biggest priority is to find ways to handle it sustainably.

This issue isn't unlike a growth issue that emerged at the University of Utah 75 years ago this year. Front-page headlines warned of a growing "crisis" of student enrollment post-World War II. The crisis got so severe the president of the university at the time even admitted they would have to consider moving the school out of where it was founded.

Bim Oliver, a historian and architect, considers it the most pivotal moment in the university's 171-year history.

"If certain things hadn't happened, and certain things hadn't been in place during this period, it's highly possible that the University of Utah would not exist as we know it today," he said.

Oliver spoke about his research into the matter during an online event held by the Utah State Historic Preservation Office on Wednesday.

Here's a look into how the university ended up facing a major enrollment dilemma 75 years ago, and how officials were able to keep the school afloat and help it thrive to become the institution it is today.

A sudden enrollment and land dilemma

While the University of Utah was founded in 1850, its "first real campus" emerged from 60 acres of land acquired from Fort Douglas in the 1890s, Oliver explained.

"Up until that point, it had been something of an itinerary institution, moving around various places in downtown," he said, adding that the state Legislature approved plans to build new structures on the land in 1896 when the enrollment was about 200 students.

The buildings that compose the campus's Presidents Circle — such as the Alfred Emery Building and the Park Building — were built in the ensuing decades after that acquisition.

The campus experienced steady growth up until the 1940s, but most of the university remained concentrated in the Presidents Circle area. Enrollment before World War II had grown to about 3,600.

Fast forward to after the war, when enrollment spiked out of control. University of Utah's enrollment had grown to 4,093 by Feb. 14, 1946. A Utah Daily Chronicle report of the time states this was a 10% increase from the previous year.

Reports from the era indicated many of Utah's schools experienced large upticks of enrollment at this time, but the University of Utah's situation was unique.

Student enrollment figures would then double by the end of the year. Another article in October that year updated the figure to 8,568 students. By that point, more than half of the students on campus were military veterans who were taking advantage of the military benefits they received from serving in the war.

Nearly 4,800 enrollees registered either through the federal rehabilitation bill or the GI bill, the student newspaper reported in October 1946. Many of the veterans also had spouses and young children.

Oliver pointed out that A. Ray Olpin, the university's president at the time, had a belief that the university should be open to almost anyone who wanted to attend. That's why the enrollment number doubled between semesters.

It also meant that the spike in enrollment didn't subside. Many other newspaper reports by the end of the 1940s show enrollment remained steady at close to 10,000 students total, especially as military veterans enrolled in classes.

The largest issue is that enrollment happened before the school could construct new buildings to match the growth. They had a whole bunch of students and nowhere to put them.

The chaos led to front page layouts in the Salt Lake Tribune, which identified it as a "crisis," and harsh criticism in the Daily Utah Chronicle. For instance, an article in September 1946 roasted the school's class registry system and the office overseeing it.

"Nobody has even told us why registration here can't be handled as simply as it was in high school where a man indicated his intention to matriculate by making an occasional appearance. The natural suspicion is that no one in the registrar's office has even been to high school," one student reporter wrote.

These news reports of the time, Oliver said, showed a "clear sense of urgency" from university administrators, students and the general public alike.

There was another issue the university ran into. It wasn't like administrators could go to one source and try to buy up land for new buildings to account for enrollment that had doubled and tripled in a very short amount of time.

The military's Fort Douglas was the primary landowner near the university at the time, but the Bureau of Land Management, Salt Lake City, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the state road commission also owned land just outside of the campus.

The need for land nearly defeated Olpin. He admitted in 1948 that the university needed another 700 to 800 acres or the school would have to move to a new location in the state.

"So imagine, if you will, in 1950, the University of Utah picking up and moving to say Fillmore or Delta or, heaven forbid, Provo. But that was, at least conceptually, a possibility," Oliver said, adding that he believed it was an "idol threat" but showed exactly the situation the school found itself in.

How it led to the campus we know today

We obviously know that the university didn't move, and it did expand beyond the original campus that existed in the 1940s. What happened to Fort Douglas during and after World War II is a major reason for that.

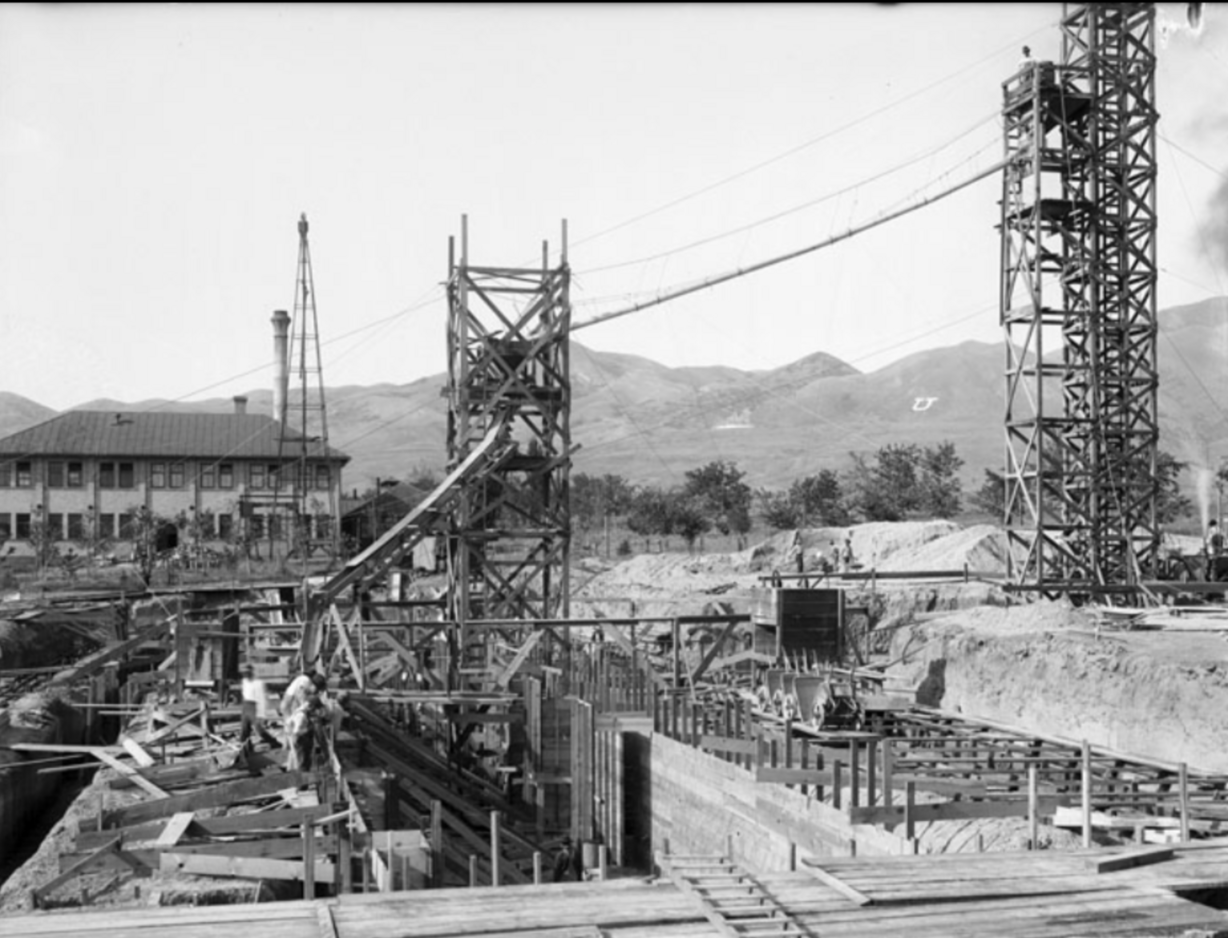

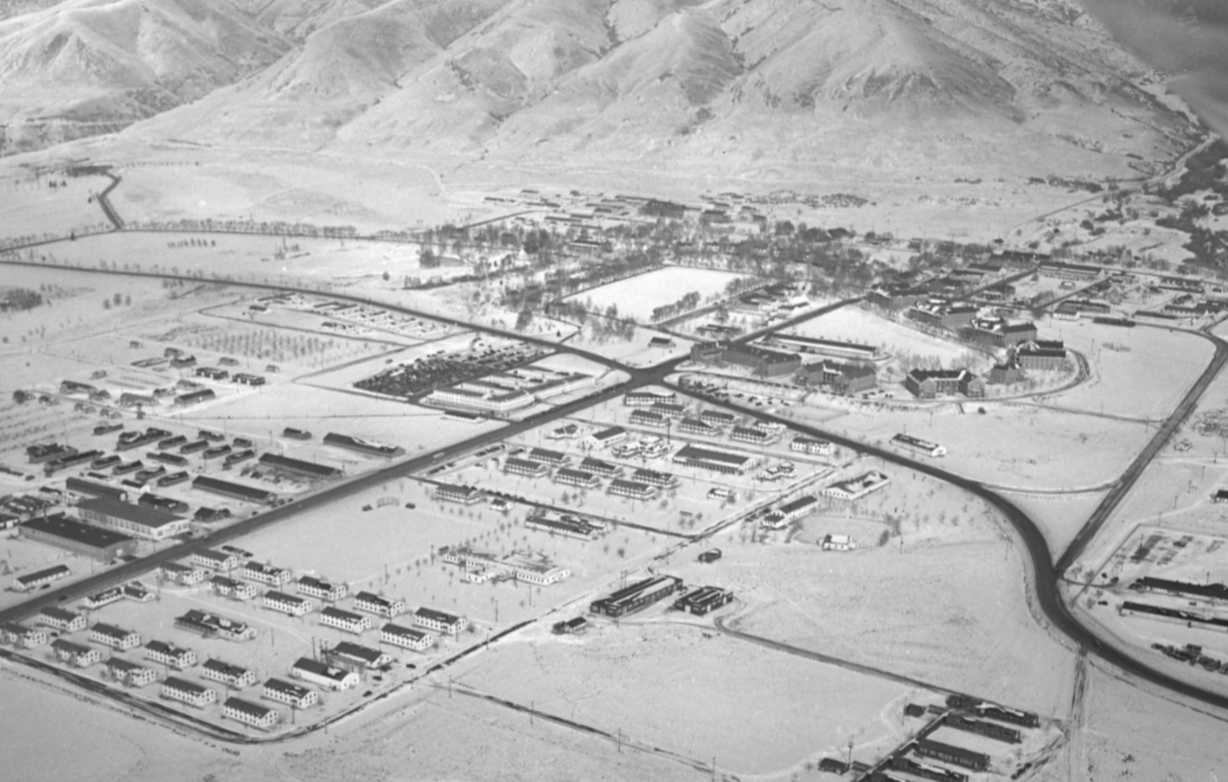

The fort became a processing center of sorts for soldiers going out to and returning from war, according to Oliver. Dozens of hastily constructed buildings emerged at the fort during this time west of present-day Mario Capecchi Drive as the fort rapidly expanded in size.

When the war ended, the U.S. military dealt with the exact opposite problem as its university neighbor. It had a bunch of vacant and unwanted buildings on its fort with nobody to put in them. As Oliver put it, it led to a "match made in heaven."

So, in 1948, Fort Douglas transferred close to 300 acres that had more than 100 buildings over to the university. Dwight D. Eisenhower, who would go on to become a U.S. president not long after, even had a role in making the land transfer happen.

"This was really the critical piece in all of this," Oliver said. "It's not the 700 to 800 acres that President Olpin was dreaming of, but it's enough to get the university to where it needs to go in the very short term. … It basically tripled the land area of the university."

Other buildings were also brought in from different areas across the state, including an old Camp Kearns building becoming the university's bookstore by 1949. The university made good use of the buildings it did receive from Fort Douglas, as well. For instance, the school turned an old Army barracks into a radiologic tech lab.

One facility, called The Annex, became the most versatile one because it expanded the university's building stock by 30% by itself. The building, at 90,000 square feet, was used for all sorts of classes and academic department offices; Oliver said it once even housed the world's largest turtle collection.

At the same time, the new space led to a new problem. The expanded campus became essentially two campuses, with buildings as far as a mile apart. And since there were many new students, campus administrators tried to ensure class schedules were tightly packed.

That meant more students needed to drive to one side of the campus or the other if they wanted to make it to their next class on time.

"As time went on … one of the primary problems for campus planners was traffic. People didn't want to walk up the hill, so they'd get in their car," Oliver said. "Now you have a traffic jam and there isn't the parking to accommodate it."

So new roads were paved to address the traffic issues, but it's also an issue that was never completely resolved, Oliver said.

Still, the land ended up the most important item. The university gradually transitioned from the buildings constructed during World War II to new, larger buildings on campus. Over 75 buildings were constructed from the 1950s to the 1970s on the land acquired in the land transfer, including the Jon Huntsman Center.

The university also went on to acquire more land with time as it expanded. The Utah System of Higher Education listed total enrollment at the university at a little more than 32,000 during the 2020-21 school year.

None of that could have been accomplished without the decision-making in the 1940s.

The end of an era and the lessons it taught

About a half dozen buildings still remain from the 1948 land transfer, but the number is shrinking. The Annex is scheduled to be demolished later this year. Oliver bemoaned that decision because the building quietly played such an important role during a pivotal moment in the university's history.

Other attendees of Wednesday's event attested to the history of the building. Julie Myers said her parents attended the university in the 1950s, and her father would joke "he didn't graduate from the University of Utah, he graduated The Annex."

"I, too, am sad to see The Annex go," she said.

However, the story from the 1940s isn't completely different from the situations emerging across the Wasatch Front today as Utah's population expands. The decisions made by the university 75 years ago are essentially the decisions that Utah government leaders and planners are working on today.

Vineyard's population boom is a result of land once owned by Geneva Steel Mill and planning is already underway for what will happen with the Utah State Prison land in Draper once a new prison opens up in Salt Lake City next year. Both share similar stories to how the University of Utah found land to expand.

Meanwhile, there are countless examples of businesses and governments that have rehabilitated old buildings and turned them into something new — much like the university also did after its crisis began 75 years ago.

"I think the real theme here that emerges from this narrative is how remarkably resourceful and creative and innovative university administrators, planners and workers were in adapting these buildings to their uses as university buildings," Oliver said. "They were totally and completely inadequate for those purposes and yet the university was able to make do with these buildings."