Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah is a desert, a fact that comes with one key ecological truth: It's not uncommon to find dry conditions.

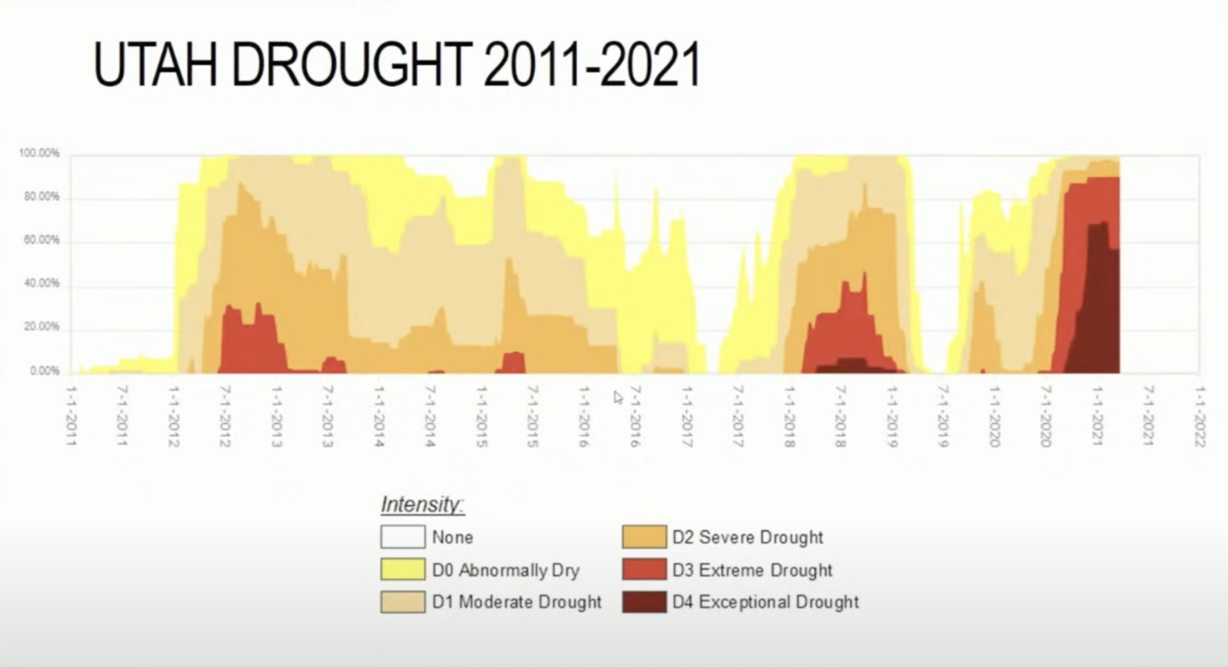

"More often than not, we are in drought, or some level of drought, and the severity just varies between year to year," said Kent Hersey, a state wildlife biologist.

But the droughts at the start of the decade are nothing like droughts seen in 2018 and the current conditions in Utah. The state experienced its driest year on record in terms of precipitation totals in 2020, and soil levels are the driest they've ever been recorded.

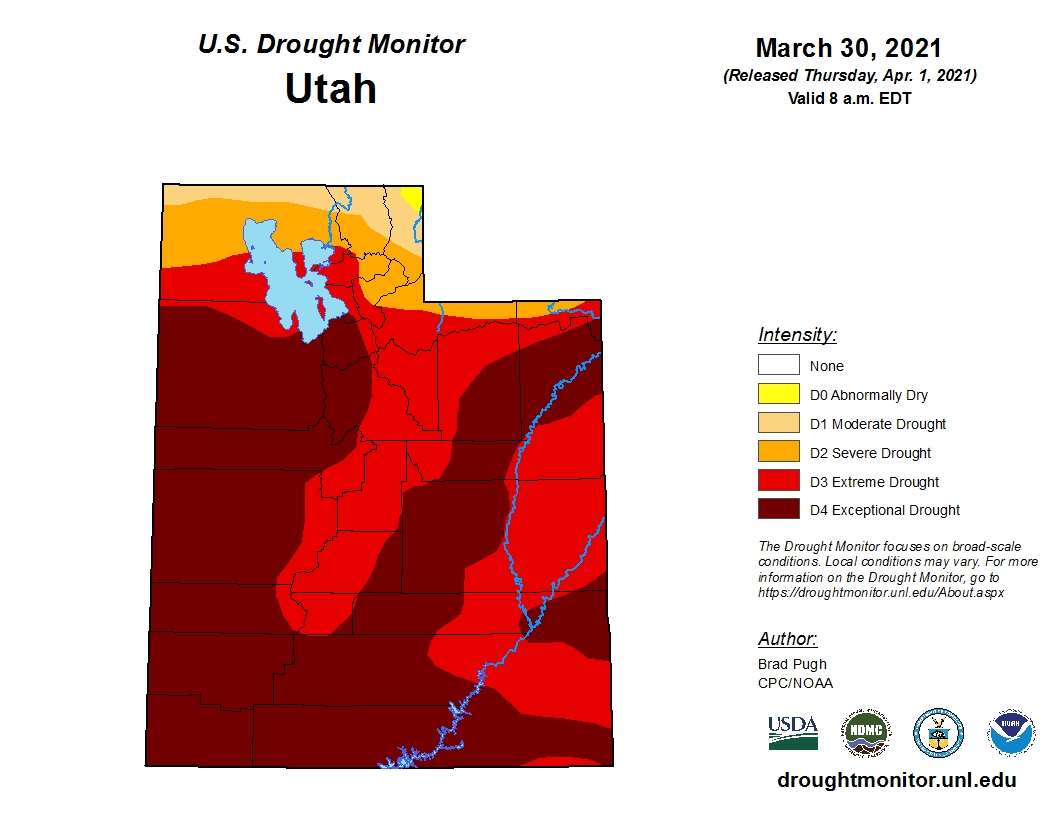

Gov. Spencer Cox issued an emergency declaration last month over the state's water conditions. The U.S. Department of Agriculture Drought Monitor made no changes to the state's drought conditions in its weekly Thursday update. It lists 90% of Utah in at least "extreme" drought conditions with over half of the state in an "exceptional drought," which is the direst category.

Utah's current drought conditions have already led to calls to conserve water, especially water waste. While there are far-reaching impacts that droughts can have on water infrastructure, they can also factor into wildlife habitat conditions.

Droughts are often tied to impacts on wildlife and, as Hersey put it during a Utah Wildlife Board work session last week, Utah is in "one of the worst droughts we've had in quite some time."

"If you look at the current Drought Monitor map, it looks horrible," he said. "It is pretty bad."

The drought conditions that emerged in 2018 — and reemerged last year — are considered a key reason for Utah's sudden decline in the estimated deer population. The Utah Division of Wildlife Resources estimated Utah's deer population at about 384,000 in 2015. It was estimated at 376,450 in 2018 but took a sharp decline in recent years. Its 2020 estimate was 314,850, which is a 16% decline in just two years. The state counted a decline of over 57,000 between 2018 and 2019 alone.

These estimates are why biologists last month proposed more than 5,000 fewer total deer hunting permits for the 2021 hunting season. The Utah Wildlife Board will consider those proposals later this month.

Related:

During a board work session last week, biologists went into further detail about how two recent severe droughts have impacted deer in the state. They said as of December they were tracking more than 1,500 deer statewide and the data from those deer helps them collect information about survival rates, body conditions, specific causes for mortality, movement patterns and helps them project populations.

The state tracking program helped biologists find connections between drought seasons and populations.

Drought and body conditions

Unlike some other wildlife like elk, moose or bison, deer pregnancy rates haven't necessarily dropped very much during dry years. But drought conditions can result in less likely survival rates for fawns, Hersey explained. He said the current survival rate for fawns is tracking to be as worse as other recent drought years.

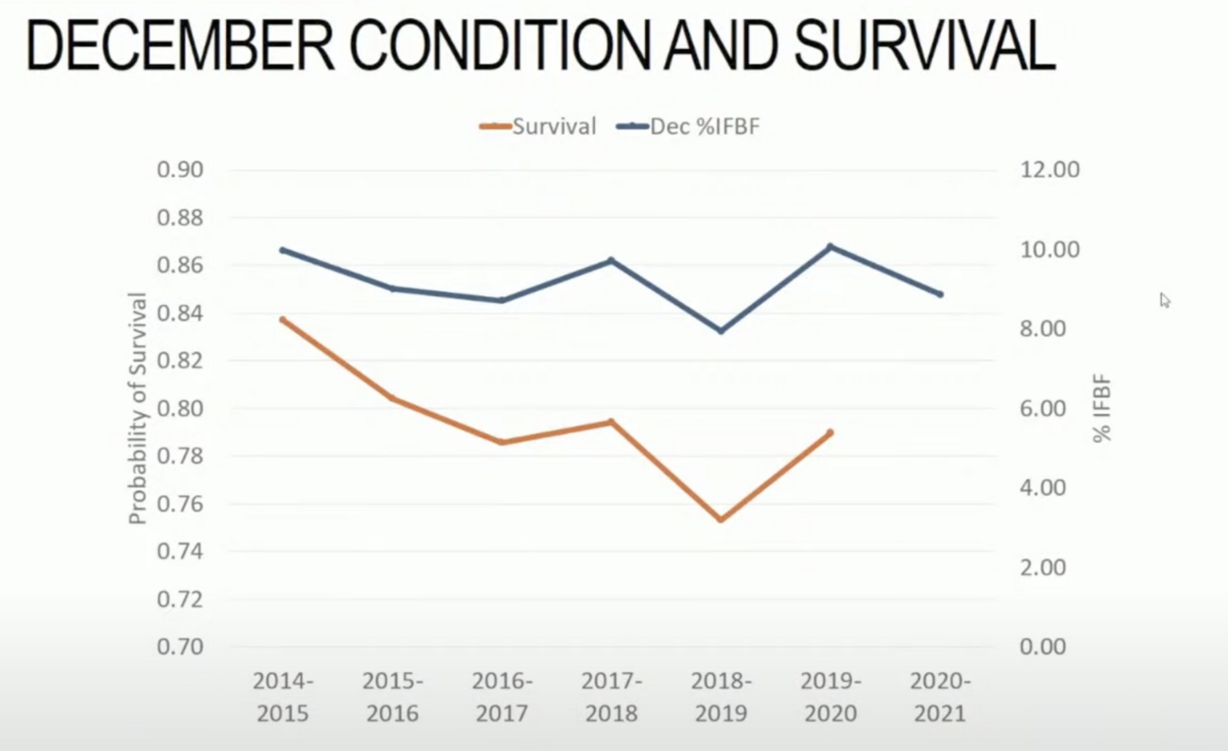

State biologists have also found ties between Utah droughts and doe body conditions. They say the fatter a deer is, the more likely they are to survive for a few reasons.

The 2018 drought, for instance, led to some of the worst body conditions of deer in recent memory, according to Hersey. He said ingesta-free body fat percentages collected a few months ago showed that doe body conditions were closing back in on 2018 levels after a prolific 2019 water year lifted the state out of the 2018 drought.

That's important because biologists have tied body conditions to deer survival rates.

"The reason they're dying is malnutrition. The skinnier you are, the more likely you are to succumb to malnutrition over that winter," he said.

The good news is that biologists found that the current survival rates for Utah does were closer to survival rates from some of the wetter years in recent history. That was something that wasn't exactly expected.

"I guess we went into December expecting pretty much disaster," he continued. "We thought we would see bad conditions across the state; however, we were pleasantly surprised. We certainly saw it in some places, but in some places we had a lot of fat on these animals and they did pretty well."

State wildlife biologists believe the differences between 2018 and now could be tied to the timing of the droughts. In 2018, there wasn't much a snowpack developed in the winter as the drought lingered while Utah had an average snowpack before the record dryness took effect in late spring through the remainder of the year.

Hersey added that there isn't as much data on bucks about this factor, but there is evidence that links drought to antler growth for bucks. If a doe is in poor shape while pregnant, the potential for antlers is reduced, he said.

"That said, the larger driving factor is actually the condition of that animal — the growing conditions for antlers during the year," Hersey continued. "If there is good spring moisture and it can put on fat and grow, it's going to make a huge difference in its antler size than if it's going to have to grow antlers in a dry area."

Drought and food

It's also why the winter-to-spring transition can also be harsh for deer.

Covy Jones, the big game coordinator for the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, explained that the seasonal change is a difficult transition time for deer because it's when their diet changes from woody browse to growing forbs.

"It's also when fawns are born and we see a lot of mortality right in and during this transition," he said. "Some deer are in such poor condition that when they transition, they just don't make it."

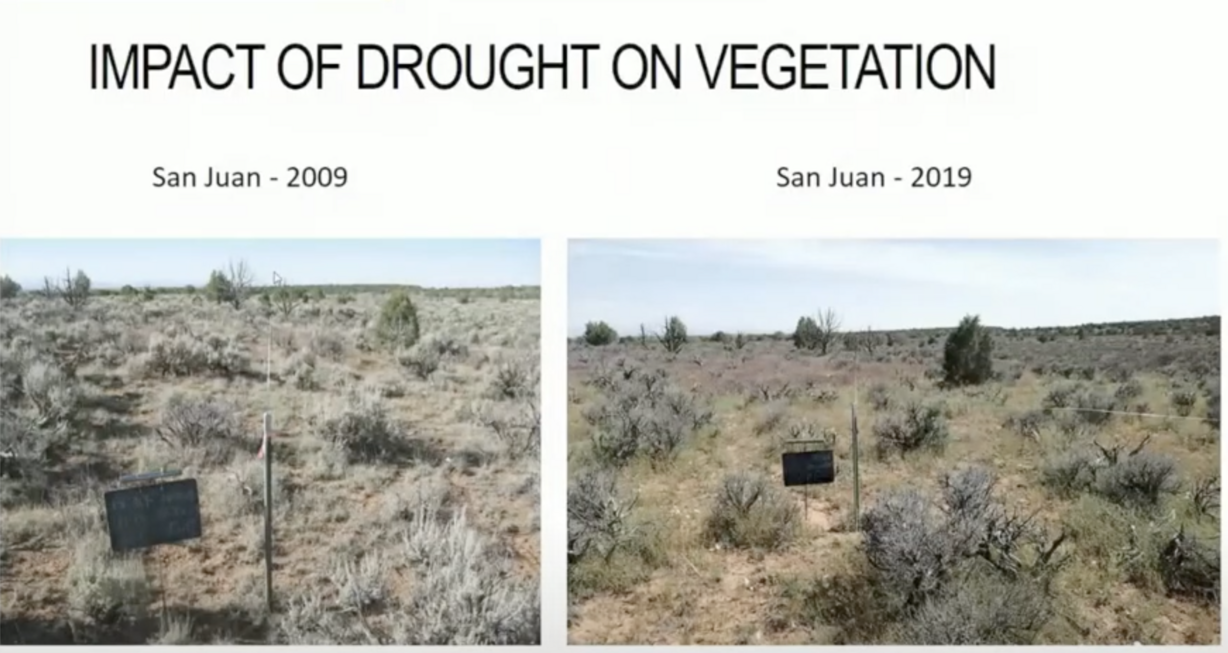

Hersey added that it can also result in less nutritional value in grass. The nutritional value of shrubs isn't impacted as much, but drought conditions can result in fewer shrubs for deer to consume.

He presented the board images of the same location in San Juan County in 2009 and 2019. The site featured a good amount of sagebrush in 2009, but a large drought in 2017 and 2018 led to a decline in plants a decade later.

"We had a large-scale sagebrush die-off, which undoubtedly will impact the winter range of these animals," Hersey said. "This is where we have to rely on our (watershed restoration initiative) treatments. Hopefully, we can restore this vegetation."

Drought and predation

This also makes deer less likely to fend off predators. Hersey pointed to data collected in eastern and southeastern Utah during drought conditions between 2017 and 2019, where there were twice as many deer killed by coyotes than years where there weren't drought conditions.

It's not just deer trying to fend off predators, experts said the predators started to seek out the deer because of the conditions, as well.

Justin Shannon, wildlife section chief for the Division of Wildlife Resources, pointed to evidence the division collected from Antelope Island over the years as an example of what happens in drought years. He said in 2006, coyotes didn't touch deer because there were plenty of rodents running around the area.

When a drought year struck in 2007, they found about 10% of the rodents they had seen in wet years. All of a sudden, the coyotes in the area went after deer.

"They were taking a lot more fawns and things like that," Shannon said. "Also in these drought years, you have a lot less cover. Fawns are hiders. As soon as they're born, they hit the ground looking for vegetation to stay in."

Other important notes

Utah's drought situation is just the tip of the iceberg in a problem developing across the region. Three-fourths of the entire West is in at least a moderate drought. The West is defined as the 11 most Western states in the contiguous U.S.

Of those 11, one-fifth of the entire region is listed as being in an exceptional drought. Arizona, Nevada and New Mexico join Utah in having some of the country's worst drought conditions at the moment; however, conditions are also very poor in northern and eastern California, western Colorado and central Wyoming, as well as pockets of Oregon.

When it comes to what that means for the deer population, Jones said the first step is identifying where declines are happening and then working to make sure that outdoor habitats are in good condition.

While the state has proposed to reduce hunting permits, he said that changes in hunting aren't exactly "silver bullets" that would solve the problem. Jones argued that it's important to control predator loads to help fawns and does survive.

Overall, biologists say it's important to have measures in place to ensure that deer can survive as drought conditions linger.

"Whatever we can do to make habitat better so these animals are coming in the best shape possible," Hersey added. "That's going to be the best thing we can do for our deer herds."