Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah is expected to receive about 32,000 COVID-19 vaccine doses each week to close out 2020 following a "miscommunication" between the federal government and states receiving vaccine doses, according to a state health department spokesperson.

The state has already listed 25,000 doses shipped, according to a Utah Department of Health update on Tuesday. The new weekly estimate means that Utah will likely fall short of the 154,000 vaccine doses it had originally anticipated by the end of December.

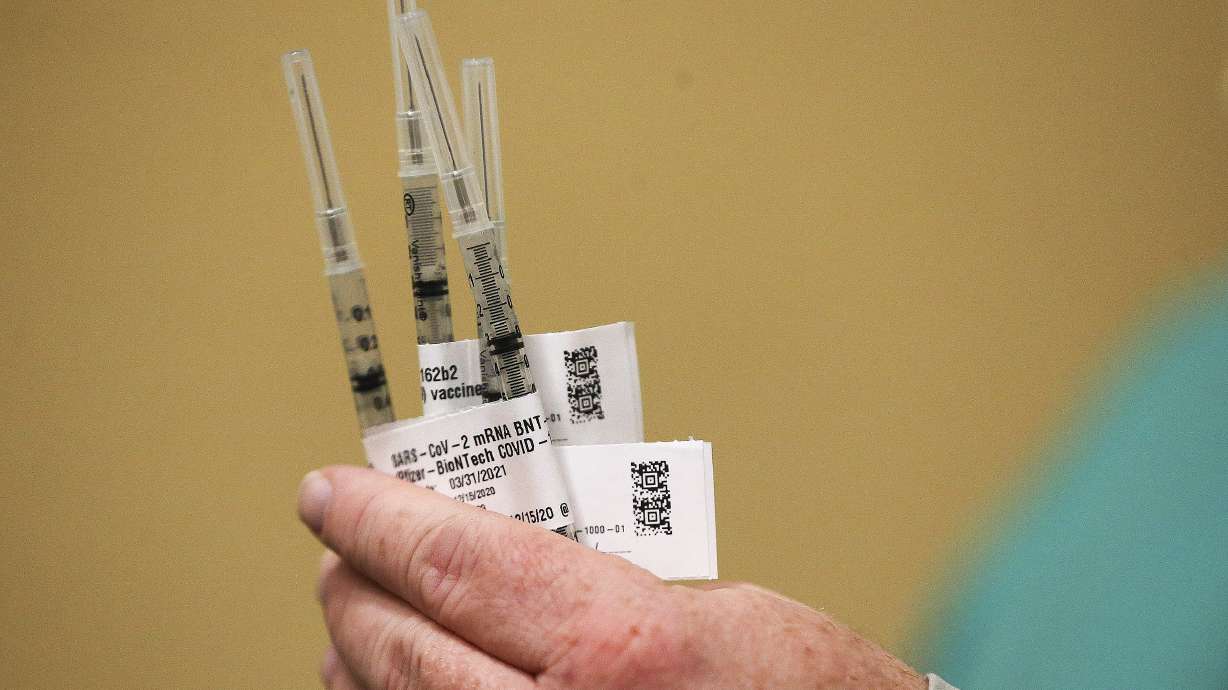

Utah was among states that reported late last week that it didn't receive as many vaccine doses that it had estimated in the first week after the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine was approved by federal regulators. U.S. Army Gen. Gustave Perna apologized for the gaffe over the weekend, calling the original estimate of vaccines to be distributed a "miscommunication," the Associated Press reported.

"I am the one who approved forecast sheets. I'm the one who approved allocations," Perna said during a telephone briefing with reporters, according to the AP. "There is no problem with the process. There is no problem with the Pfizer vaccine. There is no problem with the Moderna vaccine."

It now appears that the distribution snafu altered how many vaccines Utah will receive by the end of the year, even though the Moderna vaccine has arrived in the state.

In a series of tweets Tuesday, health department officials stated that 9,750 doses of the Pfizer vaccine from initial shipments. Of those, 86% were already administered. The department added that nearly one in four University of Utah Hospital staff had been vaccinated already.

About 61% of all vaccines delivered to date were received since Thursday, according to the department. A spokesperson for the health department told KSL.com Tuesday that Utah officials now expect 16,000 doses of the Pfizer vaccine and another 16,000 doses of the Moderna vaccine every week. If that estimate holds up, it would indicate fewer than 100,000 doses distributed to Utah by the end of the year.

It remains unclear how the adjusted figures will impact projected timelines for when certain groups, such as long-term care facility residents or teachers, will be given access to the vaccine.

Where the vaccines are going

It's been a week now since Utah health care facilities began vaccinating frontline workers. Not long after that began, the Utah Department of Health began providing statistics about COVID-19 vaccinations within the state.

About 8,518 were already administered within the state, as of Tuesday's COVID-19 update. This data may not seem overly exciting since it only reflects hospital staff at this point, but it does show that the gap between when the first five hospitals in the state received the vaccine to the next 30 health care facilities was much less than originally thought.

The health department, which estimated in November that the gap might be as long as two weeks, reported that some vaccines had been administered in all health districts but San Juan and TriCounty (Daggett, Duchesne and Uintah counties) within the first week that vaccines arrived. The first five hospitals covered just three of the 13 districts.

To no one's surprise, Salt Lake County — the health district with the most health care facility employees — had administered the most vaccines as of Tuesday afternoon. At 4,915 vaccines administered, it accounts for about 58% of all vaccines administered so far, according to the health department.

Understanding the UK's emerging COVID-19 strain

One recent international story is gaining interest among researchers worldwide, including those in Utah.

Health officials in the United Kingdom say one new variant of the novel coronavirus in the country is spreading quicker than the original strain prominent there, indicating a mutation. The strain, known as B.1.1.7, was first documented in September and accounted for about one-fourth of all cases by mid-November, Science Magazine reported. It jumped to 60% in London by the start of last week, which scientists said may mean the mutation is 70% more transmissible than the earlier dominant strain.

As noted by the New York Times, Prime Minister Boris Johnson tightened restrictions in London and many parts of southeast London in an effort to stop the spread of the coronavirus strain. Several European countries also banned travel from the U.K. as a result of the spreading mutation.

It's worth noting that experts pointed out pretty early on in the pandemic that SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, had already mutated in different strains. The bigger questions are if the U.K.'s new strain is more lethal or will disrupt COVID-19 vaccine efforts, especially if it appears in other parts of the globe.

So far, researchers say they don't think that will be the case. In an interview with KSL TV Monday, Dr. Sankar Swaminathan, chief of the division of infectious diseases at University of Utah Health, explained that the changes happened in the spike protein that the virus uses to invade human cells. He said there isn't any evidence that would lead experts to believe that it is deadlier or will thwart vaccination efforts already underway in the U.K.

The vaccine, he pointed out, helps produce antibodies in different parts of a spike protein. So when someone is vaccinated, their immune system makes multiple defenses against the coronavirus's spike protein even if parts of it have mutated.

"While it's possible for the virus to mutate and change its spike protein, it would be very difficult for it to change it so completely that the vaccine wouldn't still elicit useful antibodies," Swaminathan said.

Dr. Vineet Menachery, an expert in coronaviruses at the University of Texas Medical Branch, also said that it's unlikely that the new mutation in the U.K. will disrupt the two available COVID-19 vaccines, during an interview with NPR on Monday.

Menachery told the news outlet that it takes years of drastic mutations to form before a virus can slip past a vaccine. It's a potential long-term concern, but almost certainly not a short-term issue that would ruin vaccination efforts now underway.

"Vaccines that have been developed are really generated against — to generate a broad response. And so the vaccine uses our immune system to target multiple parts of the virus," he said. "And so in this case, we may have one or two parts that are different, but we're targeting, with the vaccines, multiple parts. And so it's really difficult for a virus to overcome that in the short amount of time like we're talking about here."

Swaminathan added that while the mutation could become the new dominant strain, it shouldn't stop public health officials from their focus to get enough vaccines administered to stop the spread of COVID-19.

Contributing: Jed Boal, KSL TV