Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — McKenzie Skiles enjoyed skiing prior to a career studying snow. Even then, she was curious about variables that impacted how and when it melted. Now, she hopes her research on dust and snow will help pave the way for better forecasting of Utah’s snowpack and ski season.

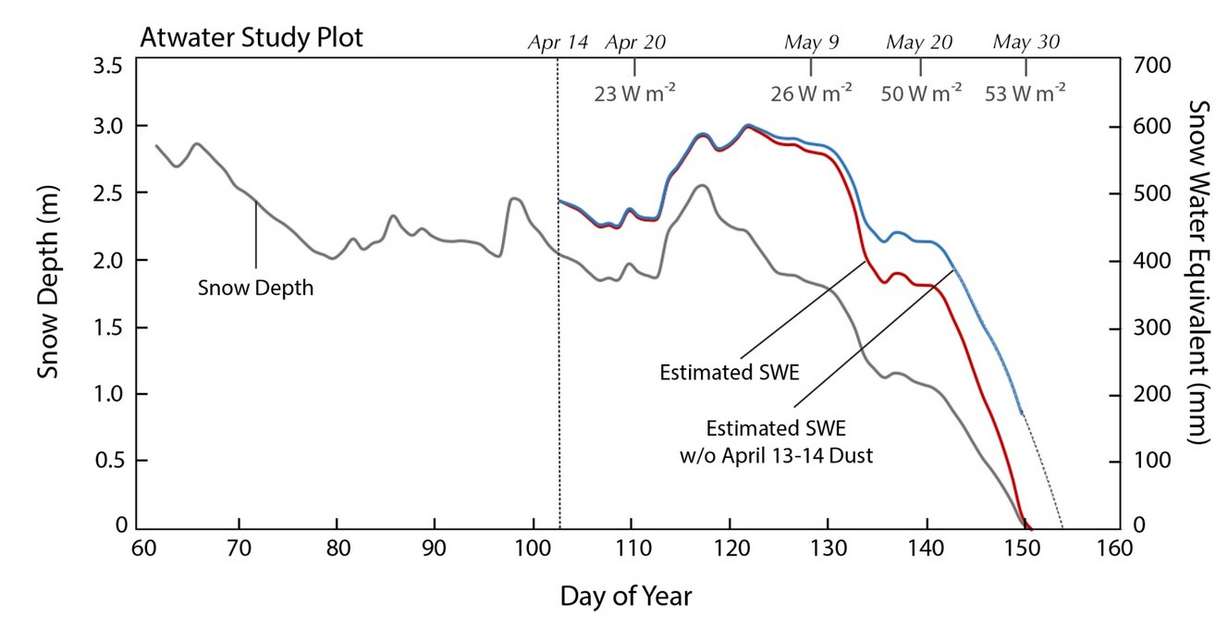

Skiles, an assistant professor at the University of Utah's department of geography, authored a study that indicates dust accelerates the pace at which snowpack melts, which is troubling because the shrinking Great Salt Lake and other sources are sending more and more dust toward the state’s snowpack.

The study, which was published in Environmental Research Letters on Friday, nearly mirrors a 2017 study she participated in that focused on the Rocky Mountains in Colorado that suggests that dark colored dust can accelerate the pace of snowmelt. While the dust flying onto Utah’s mountains is lighter in hue than Colorado’s, Skiles found that it’s still speeding up the snowmelt process, albeit, not as much.

The discovery could improve how snowpack — the amount of water contained within fallen snow (snow water equivalent) — is calculated. Snowpack is important in Utah because the majority of the state's surface water comes from the spring runoff that comes from snowpack.

Scientists already know snowpack across the western U.S. is declining. Skiles says the research on Colorado and Utah show dust may be a part of the reason why.

“Dust composition, typically in the springtime when things start drying out, makes the snow darker and makes it melt faster,” she said. “That’s not currently accounted for in our (snow water equivalent) forecasting models. It introduces errors into our understanding into when snow is going to run out of the mountains.”

It's possible that an earlier runoff could mean the state will have shorter spring runoffs and longer periods between spring runoffs each year in the future. Skiles said it's unclear if that could worsen Utah's drought situation.

Skiles and four others published a study in AGU Publications in December 2017 that found that dust from the Upper Colorado River Basin sped up the snow melt process in the Rocky Mountains by one to two months.

Researchers found the iron-rich dust there, which has a reddish hue, melted snow quicker than in areas where the dust wasn’t as dark. They determined it’s because the dark matter absorbs sunlight more than snow, which means it heats up quicker — much like dark clothing is warmer in sunlight than light clothing.

Prior to the Rocky Mountain study, a 2010 study by six different researchers found that dust impacted when the Colorado River's flow peaked.

The Rocky Mountain study Skiles contributed to focused on Colorado. She was curious if the same acceleration carried over to Utah, which has lighter dust hue.

Her team sampled dust in the air and in the snow regularly, and they found most dust came from the wind blowing from the south. That was before an April 2017 storm from the west blew in nearly half of the dust that accumulated that winter.

The storm kicked up dirt from the Great Salt Lake Desert, other dust in western Utah and also areas from where the Great Salt Lake has been drying up in recent decades. Snow in Utah melted one week quicker than usual after that storm, the researchers found.

Although the Utah results are "not as dramatic" at one week acceleration, versus the three to five weeks seen in Colorado, "it's definitely having an impact,” Skiles said.

She’s concerned because other water sources — not just the Great Salt Lake — are drying up in the state from droughts or settlement changes.

Some groups, including the Utah Rivers Council, have protested Utah’s future plans managing Bear River, the Great Salt Lake’s main tributary, because they argue that will excel the lake’s demise and spread more dust toward the state’s more populated regions. Skiles’ study argues that extra dust would impact Utah’s snowpack and also Utah’s skiing industry.

Dust is also coming from wildfires, which have become an unfortunate staple of Utah’s summers, Skiles added.

“I think we get so much dust from it just because the wind speeds get high enough and it’s newly exposed soils that haven’t been exposed in the past,” she explained.

Skiles hopes the study will help those who forecast and manage snowpack to account for dust in their projections. That would include when to expect snow to melt. She also hopes the Colorado and Utah studies will also help mountainous areas across the world figure out the impact dust has on snow to help find solutions to the problem.

“We don’t fully understand this impact and the role (dust) plays relative to other things that are impacting snow accumulation and melt,” Skiles said. “This study is just a part of that broader global story.”