Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Earlier this week, from the Utah State Capitol, President Donald Trump signed two presidential proclamations; one, modifying the Bears Ears National Monument, and a second, modifying the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Bears Ears was established as a national monument by proclamation under President Barack Obama in 2016, and Grand Staircase-Escalante by proclamation under President Bill Clinton in 1996. Will Trump’s actions be met with successful legal challenges?

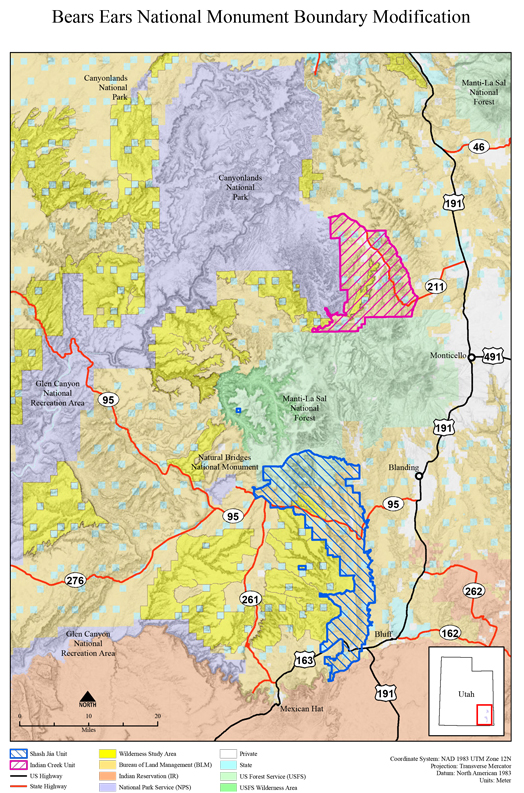

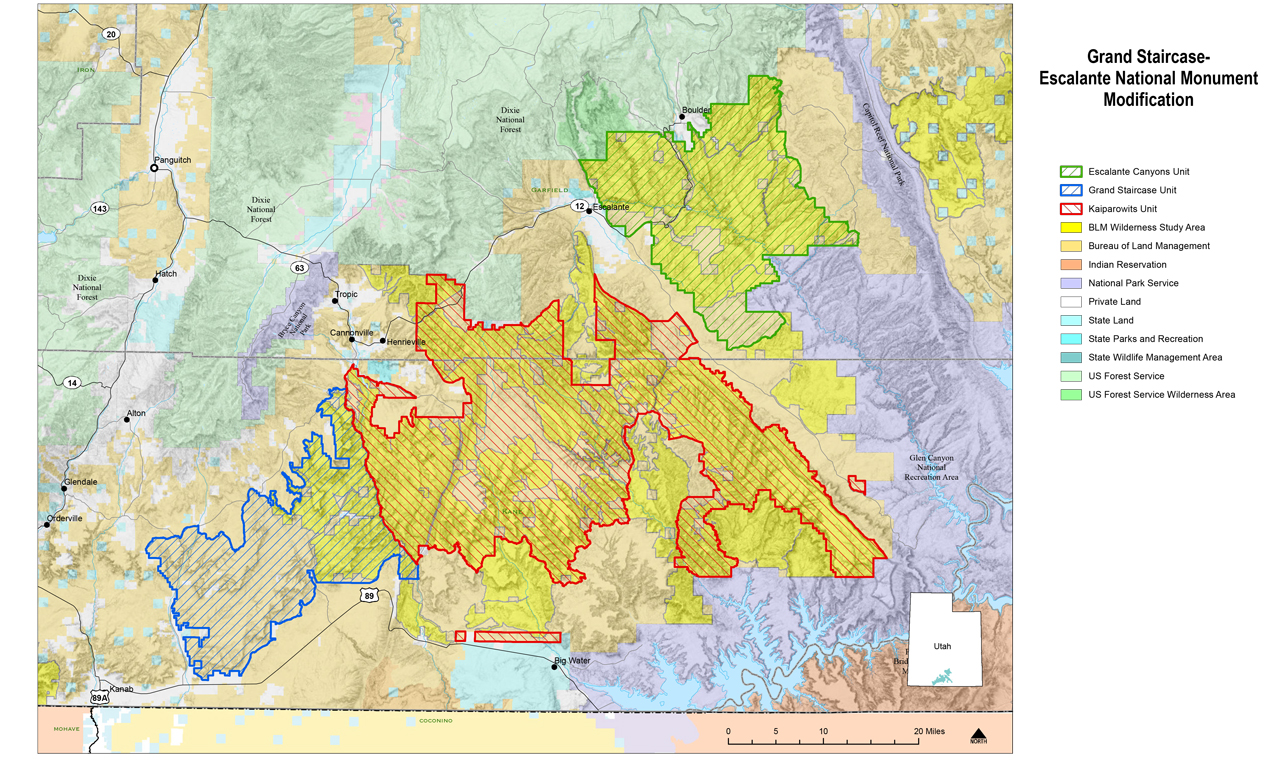

Trump’s proclamations break Bears Ears into two separate monuments, and Grand Staircase-Escalante into three separate monuments. But more consequential, Trump’s proclamations roll back federal environmental protections on about 2 million acres of land by reducing the geographic size of both monuments — Bears Ears by 1.1 million acres and Grand Staircase-Escalante by 800,000 acres.

The last time a president took action to reduce the size of a national monument was in 1963, when President John F. Kennedy revised the boundaries of the Bandelier National Monument in New Mexico by about 4,000 acres.

What legal authority do presidents have to establish national monuments in the first place? Do Trump’s proclamations undermine that authority, and will they face legal action?

Never has a president completely reversed a proclamation establishing a national monument; this would require an act of Congress. However Trump’s actions rolling back the size of these monuments could set a powerful precedent, which explains why they have been met by such strong opposition.

What is a presidential proclamation?

A presidential proclamation is one of several tools presidents use to act unilaterally — that is, without the other branches of government — to make public policy. Other tools presidents rely on to act unilaterally include executive orders and memoranda.

While executive orders and memoranda are directed at individuals inside government, like the Departments of Homeland Security or Defense, and typically have policy consequences, proclamations are directed at individuals outside of government, and rarely have policy consequences.

According to a study of presidential proclamations from 1977 through 2005, only 12 percent of proclamations issued were policy-based. The rest relayed actions that were ceremonial in nature, like declaring national holidays, such as Thanksgiving Day, or proclaiming a national month of awareness, such as National Breast Cancer Awareness Month.

However, establishing federal land as national monuments by presidential proclamation constitutes a policy-based action. The first president to establish a national monument was Teddy Roosevelt. Since Roosevelt, most presidents, with the exception of Nixon, Ford, Reagan and George H.W. Bush, have issued proclamations establishing a national monument.

George W. Bush established six national monuments. More than any other president, Obama established 26 national monuments.

While unilateral actions, such as executive orders and presidential proclamations, expand executive branch authority, they are rarely met with opposition from other branches of government. For example, according to a study of congressional actions between 1945 and 1998, only four bills were enacted that would nullify presidential executive orders, suggesting Congress is a weak check on presidential unilateralism.

Similarly, the courts can act to rein in presidential unilateral actions. However, this same study found that from 1942-98 there were just 83 cases that challenged presidential executive orders, and in only 14 cases did those challenges prevail. Thus, the other branches of government have been complicit in presidents’ tendencies to rely on unilateral actions to move their policy agenda forward.

One reason that the legislative and judicial branches do not step in to overturn or nullify presidents’ unilateral actions is because these actions are typically based on statutory authority — in other words, there are laws that enable presidents’ actions. And this is the case for proclamations that establish federal land as national monuments; presidents derive their authority from the Antiquities Act of 1906.

What is the Antiquities Act?

The Antiquities Act was passed by Congress and signed by President Teddy Roosevelt in 1906. The act gives presidents broad power to preserve land owned by the federal government that is deemed culturally, naturally or scientifically significant.

Under the Antiquities Act, presidents have secured about 850 million acres of land to preserve cultural artifacts, ruins and national landmarks. In particular, Bears Ears protects acres of land sacred to five Native American tribes that worked with the Obama administration to draft the initial national monument designation.

Each time a president has issued a proclamation establishing a national monument, the proclamation describes their vested authority, established by the Antiquities Act. For example, Obama’s proclamation establishing the Bears Ears National Monument states:

Whereas, section 320301 of title 54, United States Code (known as the “Antiquities Act”), authorizes the President, in his discretion, to declare by public proclamation historic landmarks, historic and prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest that are situated upon the lands owned or controlled by the Federal Government to be national monuments. …”

In his proclamation shrinking Bears Ears, Trump argues that Obama’s Bears Ears proclamation (Proclamation 9558) violates the act; namely that, “the area of Federal land reserved in the Bears Ears National Monument established by Proclamation 9558 is not confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of those objects.”

This language is pulled directly from the Antiquities Act, which states that the president is authorized to declare national monuments, and “may reserve as a part thereof parcels of land, the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”

While Obama’s proclamation provides justification for the geographic region established as Bears Ears, according to the Trump administration, Bears Ears (and Grand Staircase Escalante) exceed the “smallest area compatible” provision of the act. In his remarks moments before signing his proclamations, Trump also commented that the national monuments exemplify “abuses” of the Antiquities Act by past administrations.

His remarks frame the decision to shrink these parks as an effort to curb government overreach, and therefore align with small government conservative ideology.

However, his actions, by proclamation, also demonstrate an act of unilateral executive authority, and open the newly released land for drilling and mining by outside companies, which would likely limit general public recreational use.

What's next?

Given that the Antiquities Act is silent on whether or not presidents can modify or reduce national monuments by proclamation, a legal battle now looms. Although previous presidents have made minor adjustments to monument boundaries, none have been challenged in court. But that changes now.

A coalition of five Native American tribes who were each involved with the Obama administration’s efforts to protect Bears Ears have again come together to file a suit to protect the national monument as designated by Obama’s proclamation. The revisions to Grand Staircase-Escalante will also face legal challenges; multiple environmental groups, like the Wilderness Society and the Sierra Club, are teaming up to challenge Trump’s actions.

The courts will be charged with interpreting the meaning of “smallest area compatible,” and also whether the Antiquities Act implies that presidents can modify monuments, or whether the intent of the act was for the establishment of monuments, and not also for their destruction, and that the power to alter or remove monuments rests with Congress.

Regardless of the outcome, it is clear that the decision will set an important precedent for the establishment and protection of national monuments for decades to come.