Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — As far as tropical fish go, the little zebrafish is about as common as the guppy or goldfish. Active and hardy, they not only make great aquarium pets but wonderful research subjects for scientists.

Now, two University of Utah researchers are hoping they'll shed some light on opioid addiction.

The U.'s Centralized Zebrafish Animal Resource (CZAR) is a system of about 5,000 integrated tanks stacked from floor to ceiling devoted to housing several thousands of these little fish. Pharmacology and toxicology professor Randy Peterson is no stranger to the facility.

“One of the biggest advantages of zebrafish is the scale of experimentation they enable," Peterson said.

"They proliferate rapidly, and we can efficiently handle many thousands of animals at a time. This enables us to perform large-scale science, such as screening through thousands of compounds to identify new medicines or screening through thousands of genes to identify those influencing a particular condition. Experiments on that scale would be very challenging with mice, rats or primates.”

Peterson is interested in applying this large-scale approach to investigating the mechanisms related to opioid addiction. Opioids are a class of molecules that are active ingredients in many prescription painkillers and illicit drugs like heroin.

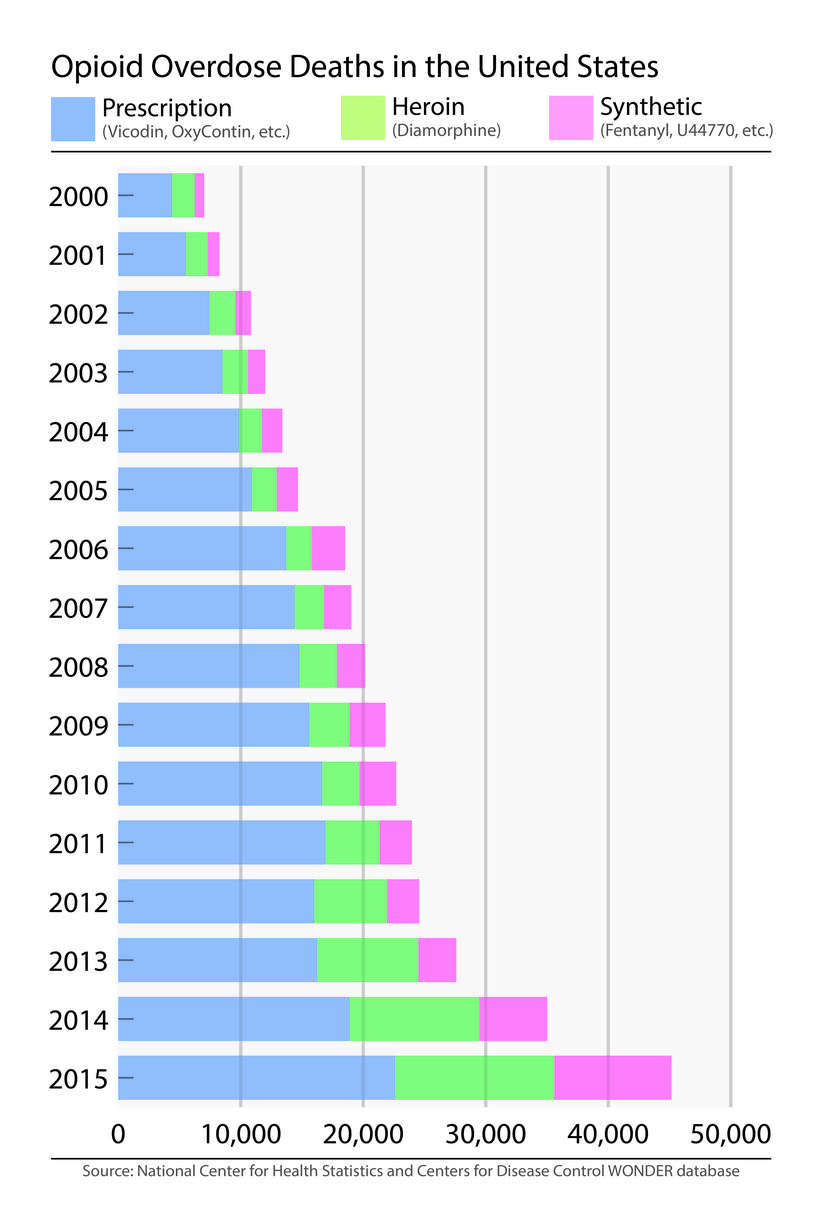

There is a sense of urgency in this work, driven by the rapidly increasing number of drug overdose fatalities seen in recent years. It is estimated that nearly 60,000 people in the U.S. died of a drug overdose in 2016.

Opioids are the cause for most of these fatalities, but the circumstances vary. Often, opioid overdoses occur via legally-obtained prescription painkillers. Other times, the street drug heroin is to blame. More recently, very potent synthetic opioids such as fentanyl or U44770 have been the cause, as it was for two 13-year old friends from Park City.

For the past two years, post-doctoral researcher Gabriel Bossé has been working with Peterson and the zebrafish to find answers about addiction. His goal has been to discover whether zebrafish respond to opioids in ways similar to humans.

Bossé set up a tank with sensors that gave the fish food when they swam over a platform. Then, when the fish learned to prompt the release of food on their own, the setup was switched to administer controlled doses of hydrocodone — the opioid used in pharmaceuticals such as Vicodin or Lortab.

Bossé saw the zebrafish were capable of administering the hydrocodone dosage at will and inclined to do so with increasing persistence and frequency. The fish were even willing to swim in shallow water to get hits of the hydrocodone — a high-risk behavior to which they would otherwise be averse.

“The fact that fish could be conditioned to self-administer opioids was in itself a surprise.” Bossé said. “In addition, the fact that they were willing to overcome personal risk and work harder for a dose were both very surprising.”

When hydrocodone was withheld for 48 hours, Bossé saw the fish were tightly grouped and reluctant to explore the tank — fish behavior that is consistent with stress or withdrawal.

Bossé found the zebrafish's brains were biologically wired like humans' to respond to opioids. These biological and behavioral similarities meant that much of what is learned from experiments with zebrafish can likely be relevant to humans.

Peterson is now using the zebrafish approach to conduct a large-scale search for new ways to understand and control addiction to opioids and other drugs.

“We are using the zebrafish self-administration assay to systematically test hundreds of candidate drugs with the hope we can discover those which reduce drug-seeking behaviors. We also plan to use the model to investigate the fundamental neuroscience of addiction,” he said.

Peterson and Bossé hope the trend of fatalities caused by opioid addiction can be reversed soon with the help of knowledge gleaned from their new experimental approach.

The researchers' article was published recently in the peer-reviewed journal "Behavioural Brain Research" titled "Development of an opioid self-administration assay to study drug seeking in zebrafish."

Robert Lawrence is a science writer and illustrator who studied biochemistry at the University of Utah and Arizona State University. You can see more of his work at: www.robertlawrencephd.com