Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

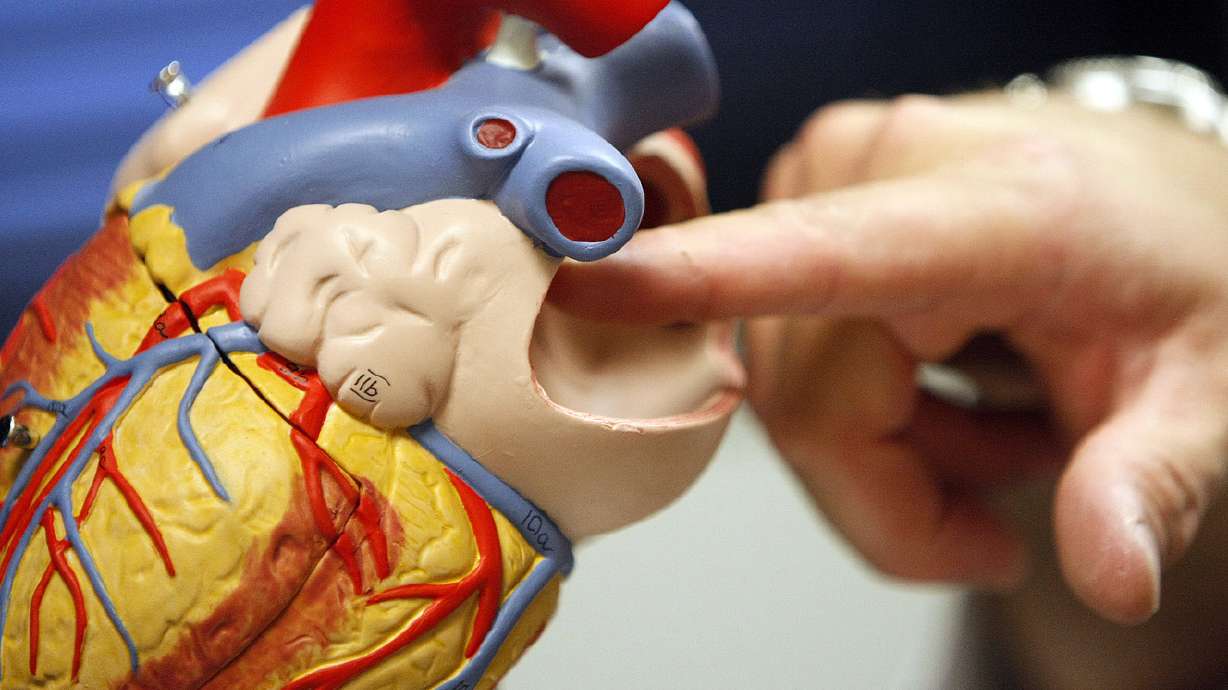

SALT LAKE CITY — Listen to the pulse of someone with atrial fibrillation and you'll hear what doctors alternatively describe as shoes flopping around a washing machine, a war drum gone wrong or Morse code gone haywire.

David Kozlowski doesn't know what atrial fibrillation sounds like. He only knows what it feels like: his head getting light, his lungs locking up, and then his heart dropping and jumping, as though he were stuck on the Tower of Terror ride at Disneyland.

Atrial fibrillation — rapid, irregular heartbeat — is the most common heart rhythm disorder in the U.S. But what causes persistent or permanent atrial fibrillation is still little-understood, and how to best treat it is still debated.

Cardiac electrophysiologists like Dr. Michael Eifling, at St. Mark's Hospital, have usually treated atrial fibrillation with medicine, electrical shocks or something called catheter ablation — a procedure designed to redirect the flow of electricity in the heart.

Cardiac surgeons like Dr. David Affleck, with MountainStar Cardiovascular Surgery, have usually attacked atrial fibrillation with a surgical version of the procedure.

Still, time and time again, there were patients they couldn't cure.

"I'd do my procedure, they'd do great for some period of time, and then they'd have a recurrence," Affleck said. "And I didn't know why."

With new treatments being developed at a rapid pace, doctors still disagree over how to best treat atrial fibrillation. Now a new type of treatment — one that's still debated among experts — is showing promise in Salt Lake City.

A perplexing case

Kozlowski, a marriage and family counselor who looks far younger than his 41 years, was diagnosed with atrial fibrillation in 2009 after he blacked out at a sushi restaurant in downtown Salt Lake City.

An EKG revealed he was in atrial fibrillation. "The other doctors were going to take me on more medication, ablations and then try to shock my heart back into rhythm," Kozlowski said. "The problem was none of those doctors actually believed it would work."

Things started getting worse last year. Kozlowski blacked out again, last winter, after Brazilian jujitsu sparring practice. Two weeks before that, he started feeling dizzy while driving his 5-year-old daughter home. He pulled into a nearby parking lot and laid down for half an hour, fighting for breath.

Kozlowski also found that the anxiety was causing him to carry stress from his job into his home. As the founder and leader of a support group for teens, Kozlowski would get home feeling depressed, unable to absorb what had happened that day, worn to the bone.

"I don't know how many more years I can do this," Kozlowski remembers thinking.

His doctors, at a loss, referred him to Eifling, unsure if Eifling could help him.

The way Kozlowski tells it, "Dr. Eifling saw my history from '08 and then all the way 'til now, and he was like, 'Get this guy to me right away.'"

Which treatment is better?

There's no consensus among doctors on how to treat atrial fibrillation, according to Dr. Nassir Marrouche, a cardiac electrophysiologist at University Hospital and the founder of the U.'s Comprehensive Arrhythmia Research & Management Center.

Part of the problem is that the disorder is still not fully understood. Another is that researchers have been rapidly developing new ways to measure and treat atrial fibrillation in recent years.

"I have six new technologies on my desk," Marrouche said. "We're trying to test them as we speak."

If you had asked him in 2003, Marrouche would have said they found a cure for atrial fibrillation. The procedure, called catheter ablation, involves inserting a thin tube into the heart and using a machine to burn or freeze heart tissue. The scar tissue redirects the electrical flow of the heart to the correct places.

Doctors soon realized catheter ablation didn't work as well as they thought. For those with persistent atrial fibrillation, it was successful about 45 percent to 60 percent of the time. But patients often required multiple ablations. And for people like Kozlowski with long-standing atrial fibrillation, catheter ablation almost never worked, Affleck said.

"Today, we're very careful using the word 'cure,'" Marrouche said. "We say we're 'suppressing' the irregular rhythm."

People with atrial fibrillation often don't realize how serious it can be. Somewhere between 2.7 million to 6.1 million Americans live with atrial fibrillation. Each year, it contributes to 130,000 deaths a year.

Many are racing the clock. Because atrial fibrillation causes the heart to quiver rather than pump, blood in the heart coagulates, forming a jelly or sludge — a breeding ground for clots. The risk of stroke for a person with atrial fibrillation is four to five times higher than someone without it, and they are usually more severe.

Doctors disagree on the effectiveness of a new treatment that has hit the field: hybrid ablation. The blended procedure that combines the surgical approach Affleck usually takes with the catheter approach Eifling usually takes.

Jess Gomez, spokesman for Intermountain Medical Center in Murray, said hybrid ablation approaches are "still controversial."

"There's not a lot of data on the effectiveness of this procedure just yet," Gomez said in a statement. He added that the hospital does not perform the procedure outside of special exceptions or research.

Marrouche also expressed skepticism. "Cost-effectiveness, long-term data — that's what we need to look for," he said. He argued that doctors should focus on fixing the underlying problem that is causing traditional ablations to fail: diseased heart tissue.

Eifling admits the procedure is "a big hammer," reserved only for the most serious patients, like Kozlowski. But he and Affleck say there are enough examples of people with successful outcomes to show hybrid ablation works.

They'll also point out that even the best heart doctors don't have an answer for patients with long-standing atrial fibrillation who haven't responded to other treatments.

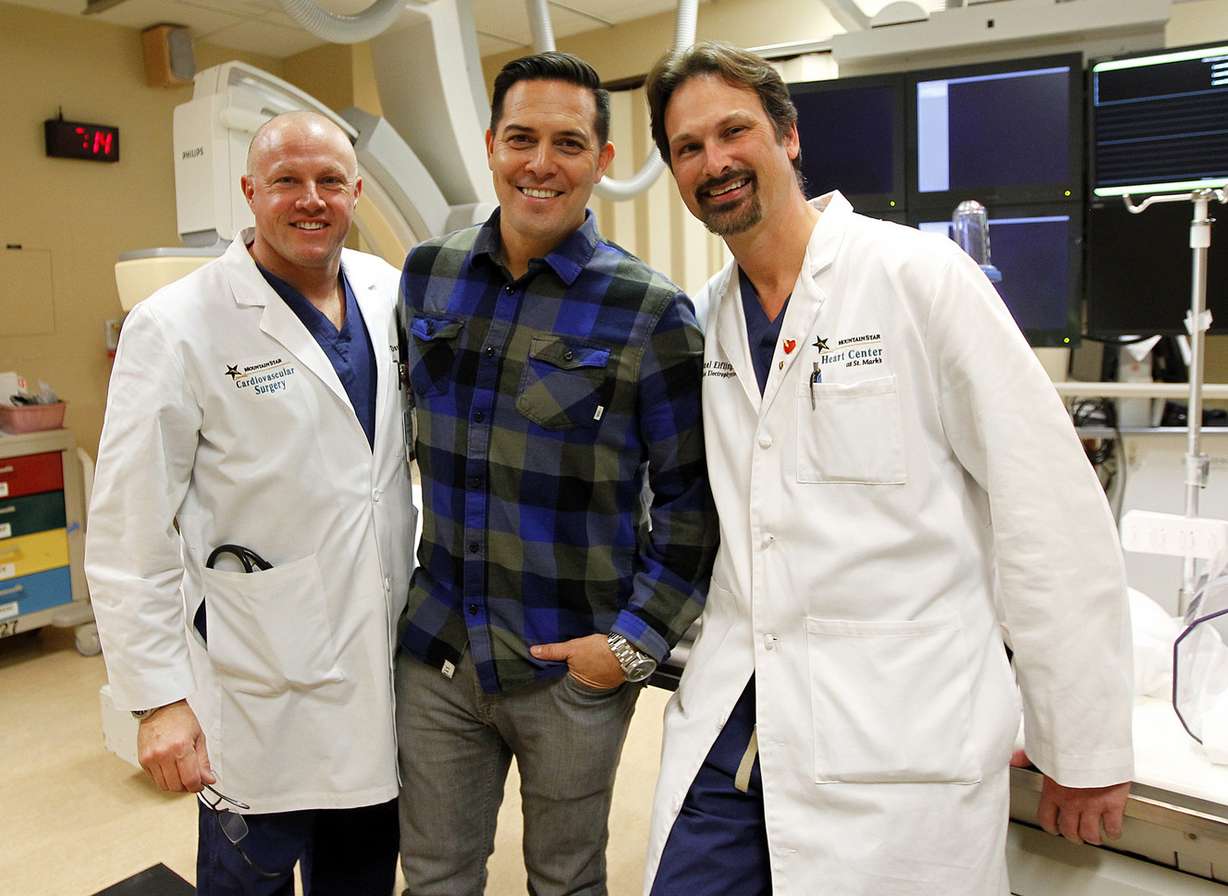

Affleck, Eifling and a third doctor, Dr. Peter Forstall, an electrophysiologist at Ogden Regional Medical Center, became the first in the state to offer hybrid ablations last year.

It's an uncommon setup. Usually, heart surgeons like Affleck and heart rhythm doctors like Eifling are locked in a "turf battle" over patients, Eifling said.

But even Kozlowski noticed that Eifling and Affleck have a rapport. Both are heart doctors with a bit of an edge: Affleck, with his penchant for Mountain Dew Code Red and Motley Crue, calls the tedious work of ablation a "labor of love." Eifling, an amateur Corvette racer who has led several medical expeditions to the Himalayas, still insists that "racing cars is not as much fun as cardiology."

The hybrid ablation procedure is a blend of their two specialties: First, Affleck inserts a tube through a few small incisions in a patient's chest and makes a series of controlled burns on the outside of the patient's heart.

Three days later, either Eifling or Forstall go in with a catheter and redo any spots Affleck might have missed from the inside of the patient's heart, creating a "firewall" of scar tissue that stops erratic electrical signals in their tracks.

Kozlowski still remembers Affleck walking into the lab to start the procedure, wearing a St. Louis Cardinals surgical cap.

"It felt like Bruce Springsteen crossed with a Navy SEAL was coming in to give me surgery," Kozlowski said. "I was like, 'All right. This might work!'"

Finding his rhythm

On a Friday afternoon, six months after his surgery, Kozlowski is visiting with Eifling and Affleck, joking with them like old friends.

From start to finish, the hybrid ablation took five days in the hospital, including three days of rest.

Since then, Kozlowski says, he hasn't been out of rhythm once. That pounding, fluttering feeling in his chest is gone. So is the breathlessness, and the dizziness. He's not on a single medication, and the former Ute wide receiver has also returned to jujiutsu at nearly 90 percent of his former strength.

Kozlowski is one of about 40 patients who have undergone the hybrid procedure with Affleck, Forstall or Eifling. So far, St. Mark's and Ogden Regional are still the only hospitals in the state that offer the procedure.

Eifling and Affleck said they foresee hybrid ablation becoming the new standard for tough atrial fibrillation cases.

Marrouche and Gomez expressed doubt. Gomez said doctors at IMC would consider offering it once there is enough randomized data showing its benefit.

Several ongoing trials — including one led by the Mayo Clinic — should provide new information on the effectiveness of traditional ablations in coming years.

Kozlowski is just happy that it's over. Now he's focused on growing Quit Trip'n, his youth support group, which is expanding to a third location in Park City.

Other than some scars on his chest and a heart monitor in his pec, there is no sign — and barely any memory — of his six-year ordeal.

Earlier that day, Eifling relayed a conversation he had with Kozlowski.

"Hey, man, how's it going?" Eifling had asked.

"It's good, man," Kozlowski replied, smiling. "I don't even think about a-fib anymore."

Daphne Chen is a reporter for the Deseret News and KSL.com. Contact her at dchen@deseretnews.com.