Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

LOGAN — The Utah Department of Transportation and Division of Wildlife Resources are getting a better grasp on the details of wildlife-vehicle collisions across the state thanks to a mobile application developed by Utah State University researchers.

Traditionally, UDOT contractors would record on paper the location of an animal carcass to the nearest highway mile marker and submit the data to someone else to be entered into a spreadsheet. At times, the process resulted in errors, and weeks would elapse before the information became available to transportation and wildlife officials.

"It became apparent that we could streamline the process and make it a lot easier for everyone to use that information," said Daniel Olson, who headed the project as a doctoral student at USU. "With our modern tools, especially smartphones, we can do a little bit better."

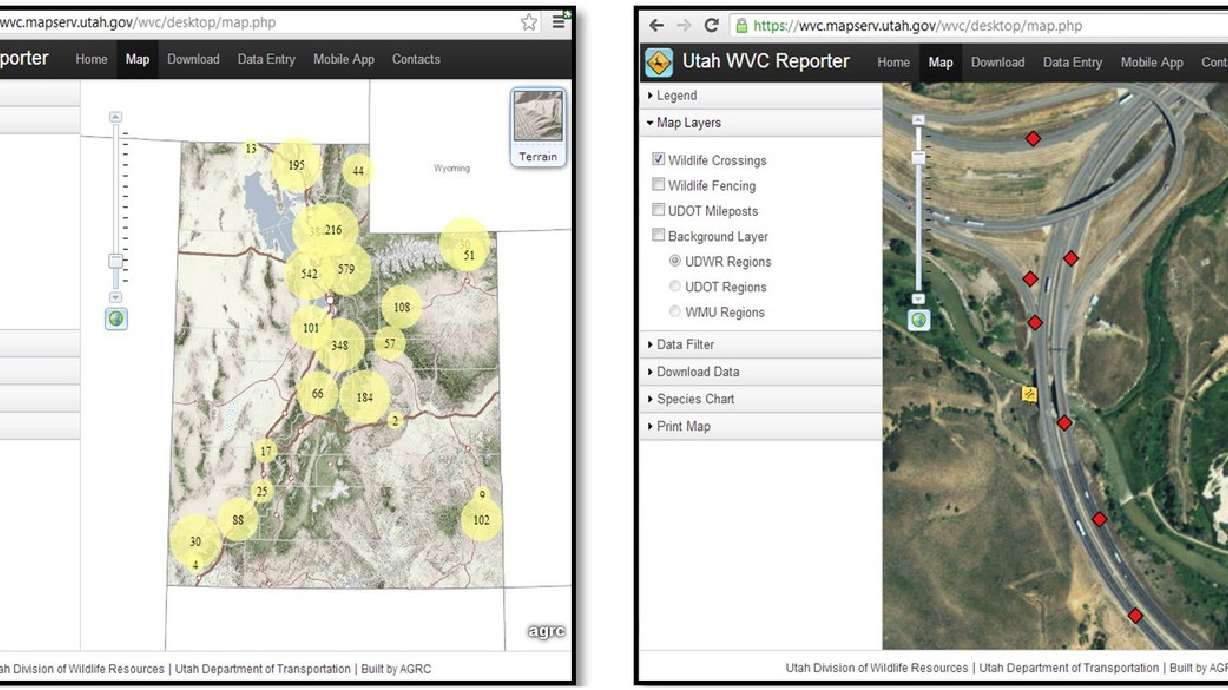

Olson's research team collaborated with UDOT and DWR to create a standardized system for reporting wildlife-vehicle collisions more accurately and efficiently using a smartphone app. UDOT commissioned $30,000 toward the project, and the app went online in 2012.

Officials have since recorded the species, gender and location of each carcass as it was collected. Instead of relying on proximity to mile markers, the app uses GPS capability in smartphones to determine the carcass' location within a few feet, Olson said.

In the app's first year, UDOT and DWR logged 6,822 carcasses, 85 percent of which were mule deer, according to a study published in PLOS ONE in June.

The roadkill app has really helped us see where the hotspots are and where there might be holes in the fence. So we've actually gone and followed the data that shows where the animals are getting onto the road and getting killed and then looking for the holes in the fence and fixing them.

–Patricia Cramer, USU research assistant professor

"It's gruesome," said USU research assistant professor Patricia Cramer. "It's really a bummer."

While the app has revealed high numbers of wildlife fatalities, Cramer said it also helps transportation managers identify areas prone to collisions and plan accordingly.

"The roadkill app has really helped us see where the hotspots are and where there might be holes in the fence," she said. "So we've actually gone and followed the data that shows where the animals are getting onto the road and getting killed and then looking for the holes in the fence and fixing them."

Cramer's research has focused on finding solutions to wildlife-vehicle collisions, such as structural wildlife crossings.

While "stand-alone wildlife mitigation" structures are rare, UDOT incorporates data collected from the app while planning other projects, such as road preservation, according to UDOT environmental services director Brandon Weston.

"We have the use of that information the second it's collected in the planning of our projects," Weston said. "So we can overlay that data with upcoming road projects to see … if there are small things we can do: Can we add a little piece of fencing, or make a longer bridge than we were anticipating to accommodate wildlife crossings? It gives us those opportunities."

After using the app, UDOT and DWR have identified an area on U.S. 191 between Monticello and Blanding, as well as sections of U.S. 89 between Sterling and Mt. Pleasant, as sites for future mitigation projects, according to DWR habitat section chief Ashley Green.

The app is currently available only to UDOT, DWR and research officials who collect the carcasses, Green said.

"If we had everybody using it — sometimes these animals are laying there for a day or two — that same deer or elk carcass might get logged multiple times, which would skew the data," he said. "We're trying to make sure it's collected in a standardized manner so we can get a good estimate of the number of animals being killed."

Olson said he is pleased to see the app being used daily to enhance safety for motorists and wildlife.

"It's satisfying because it was really a team effort," he said. "This is really cutting-edge stuff. It's something that's definitely benefited the people in the state."