Estimated read time: 2-3 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

John Hollenhorst reportingIt's not often that a work of art has to be fenced off to protect the public and to protect the art from the public. But that's exactly what's happened in Utah. And it's raising some questions about one of the most unusual sculptures anywhere.

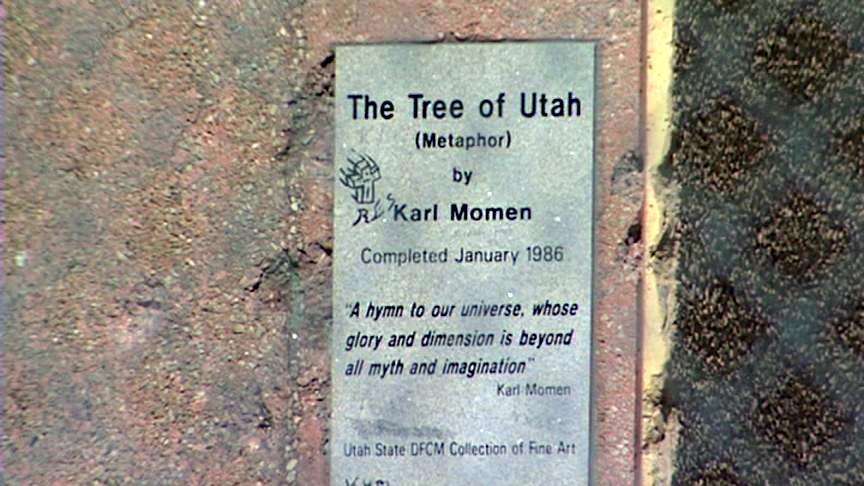

If you've ever driven to Wendover, you've seen it, Karl Momen's huge sculpture called "The Tree of Utah."

A little bit at a time, it's disintegrating, and some are wondering why no one's spending money to maintain it. We have some answers.

"The Tree of Utah" is probably Utah's most often-seen artwork. Nearly 5 million people pass by every year on Interstate 80.

It may not be everybody's cup of tea. The monumental sculpture certainly catches the eye; sometimes delighting, sometimes puzzling passersby.

Still it does belong to the people of Utah, and now, the people are fenced out.

Since last year, a chain-link fence and barbed wire has been keeping art lovers, and everyone else, away.

Like leaves from a real tree, pieces of tile are falling off and scattering across the desert.

Even art historian Hikmet Sidney Lowe thinks the fence is probably necessary. "The work is crumbling, and so we don't want people to be damaged, of course, by these tiles and be hit with them, and conversely, keep people away because there's graffiti," Lowe says.

You can't blame people for stopping. There's not much else out to see, and this thing's oddball enough that it's irresistible to some people.

Unfortunately, instead of admiring it, people shoot at it, scar it, and even tear off pieces as souvenirs.

When he donated the sculpture to the state, sculptor Karl Momen agreed to fund a maintenance program himself, but never came up with enough money.

Lowe says unless the tree is going to be demolished, the state has a responsibility to spend money on maintenance. He says, "If we are going to be stewards of art, we want to show our art in the best light possible to people who are driving by. Thousands of people go by every single day, and that's a work of art that represents our state."

Just a few months ago the sculptor donated some other artworks, which state officials are planning to convert into a cash endowment.

They say there's no structural problem and no emergency, but they hope to have money available for maintenance as it's needed.

The fence, unfortunately, is probably a permanent addition to the sculpture.