Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

- Salt Lake County explores adopting Miami-Dade County's model to address homelessness and criminal justice.

- Miami's approach reduced arrests and jail populations via changes in addressing mental health in the justice system.

- Salt Lake leaders aim for a strategic plan release next month to implement changes.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah and Salt Lake were mystified by what they saw when they toured Miami-Dade County to see how leaders there handled "high utilizers" within the homeless population during a trip three years ago.

The Florida county was more than two decades into a problem that pulled people experiencing mental illness out of the criminal justice system and placed them in community treatment programs by that point. Officers were also given training to better identify people experiencing a mental health crisis, and also how to deescalate these types of confrontations under the program.

What's often referred to as the "Miami model" became wildly successful. Arrests in Miami-Dade County were cut in half, from 118,000 per year to 53,000, while the jail population dropped from 7,400 to 4,400, the National Judicial College noted in 2023.

Utah's most populous county is now hoping that the model's chief architect can help turn around its homelessness and criminal justice systems similarly.

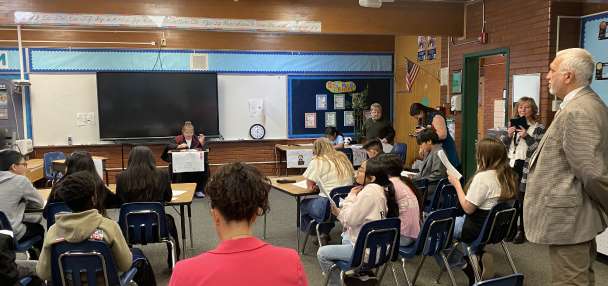

Salt Lake County leaders — and others — met with an influential former judge who crafted the Miami model on Monday, marking the third and final meeting before a "strategic roadmap" and a plan to implement changes going forward is scheduled to be released next month. The report is expected help guide a "real system of care" to address homeless resources and criminal justice in the county.

"I believe there is (an) opportunity for our county to restrategize (and) better coordinate our resources to tackle the complex challenges we face in a way that will drive results," said Salt Lake County Council Chair Dea Theodore.

What is the Miami model?

The Miami model originated in 2000, when Steve Leifman was an associate administrative judge for the Miami-Dade County Court. A former Harvard student who was accused of a minor offense had a psychotic episode in the courtroom, which led to a psychiatric evaluation that determined he had late-onset schizophrenia.

He was incompetent for trial, and the only option at the time was to release him back onto the streets, where Leifman knew the man would remain a danger to himself and possibly others.

"None of us go into our professions to be that kind of problem," he said, reflecting on that decision 25 years later. "His case really was a window into everything that was wrong with both the response to the criminal justice system and the response from the community mental health system."

That case inspired a drastic shift in handling mental health in the county's court system, addressing how jails had become "psychiatric warehouses." The county decided, at the end of a two-day summit, that the best way to handle the issue was a complete rewrite of their criminal justice playbook.

Miami leaders were impressed by a 40-hour officer training program in Memphis, Tennessee, which they came across. It trained officers in how to identify people in crisis and safely take that person to help without taking them to jail. They also found ways to get people into treatment while tasking the court with monitoring people to make sure they got the treatment they needed, fixing a gap they had found in the court system.

It didn't happen overnight, but both adjustments led to a decrease in the county's jail populations and more.

"Our recidivism among our post-arrest diversion system for misdemeanors went from 75% to 20%, and, for the felony individuals, it went from 75% to 6%," Leifman said.

Countywide homelessness also dropped from over 8,000 to less than 1,000.

Seeking a repeat in Salt Lake

Leifman ultimately launched a consulting firm that helps expand the Miami program to other parts of the country experiencing similar issues after retiring from the bench last year. Having seen the program first-hand, Salt Lake County officials jumped at the opportunity to retain him as they navigate current challenges.

The county's jail has become "the state's largest mental health provider," and approximately one-third of that population is immediately homeless when they're moved out of jail, county officials say. A recent audit also highlighted a recidivism problem caused by jail overcrowding.

Both sides said Monday that they hope to create a "seamless system" that addresses behavioral health issues among those coming in by assigning them to appropriate resources, which they hope can replicate Miami's results.

What helps is that Salt Lake already has "effective assets," and all the tools for successful, Leifman said. He points to a crisis center that opened in South Salt Lake earlier this year as an example, calling it one of the best in the country right now.

The only problem he sees is a lack of coordination between agencies over these resources.

Some of this is slowly improving, using an approach similar to Miami. State and local leaders launched a program that helped reduce jail bookings among the system's highest offenders, which are down 28% over the past six months, as people have been directed to crisis centers or shelters in certain circumstances, Salt Lake City Police Chief Brian Redd said last week.

This is a long-term endeavor. We need to steer the barge in the right direction.

–Salt Lake County Mayor Jenny Wilson

Next month's "strategic roadmap" and implementation plan may help create more connections within the system countywide. It'll be part of a partnership that county leaders want to continue beyond 2026.

State and city leaders have been excited for the findings, said Salt Lake County Mayor Jenny Wilson. It's unclear yet what the cost will be for any changes, but she believes the county could receive support from the state and its philanthropic communities, based on the interest brought up in meetings.

Wilson also believes the plan should at least improve spending efficiency in the costly public safety realm, if it doesn't save money altogether. Whatever the case may be, the county is aware that results may take time.

"This is a long-term endeavor," she said. "We need to steer the barge in the right direction."