Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — It would seem as though it has never been more popular to be British.

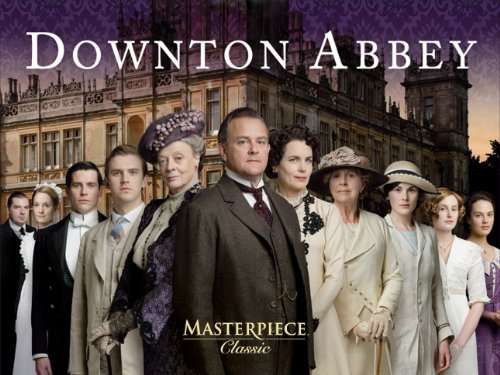

The latest U.K. import to American television screens, Downton Abbey, has amassed a cult following in the United States as its second season nears an end. The show, set at a Yorkshire estate on the cusp of World War I, tells the story of the Earl and Countess of Grantham and their three daughters, as well as of their myriad household staff.

Their world — a world far removed from most Americans — is a world of butlers who appear at the snap of a finger, of chauffeured rides in still-rare automobiles, dinner parties and aristocratic values. It is the pageantry and propriety of a bygone era.

In the midst of a historic ongoing protest against wealth and entitlement — for which the wealthiest 1 percent have become unwilling poster children — one would expect a show about landed aristocracy at an English country estate to be rejected, even ridiculed, for espousing the very values many are trying to discredit.

But as the second season of the critically acclaimed series comes to an end Sunday in the U.S., one would think it has never been more popular to be an aristocrat. Viewership has grown within the U.S. to average more than 6 million viewers a week, drawn to PBS on Sunday nights to revel in the early- 20th-century dramatics of the Edwardian privileged. And Downton was the second-most-viewed show in the U.S. on Superbowl Sunday, behind only the main event itself.

But perhaps that is what Americans are looking for: stability. A sense of everything being in its proper place at a time when it seems as though nothing is. Downton is a story, above all, of keeping order.

It is also a story of war, though, between both countries and classes. Season one opens to what will become the ongoing focus of the season: finding a male heir for the estate so the Crawley family can avoid losing everything. Class tensions are highlighted as the Earl and Countess' three daughters struggle with forbidden love and broken dreams, sometimes wanting to cross the rigid divisions but struggling to find a way.

It is no surprise, then, that Americans have been so taken by the story. Downton Abbey is, upon closer inspection, a story of crossing lines, of redrawing boundaries. The storyline seems at first to be one of rigidity: the upper classes going to lengths to maintain the status quo. It is in the younger generations, though, that a sense of misgiving is seen: could the values they had long held dear be the very root of their unhappiness?

Two conflicting worlds collapse into one, then, as characters fight for both consistency and change. They keep to the status quo while in secret detesting it; they do not know another way. And Americans, for whom to many challenging the status quo is what the American dream is all about, love a story about freeing oneself from socially imposed boundaries.

"Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breath free," reads in part the plaque in the base of the Statue of Liberty. America, built on the sacrifices of generations of those who yearned to free themselves from oppression, has long been seen by those who struggle elsewhere as a land of opportunity. Now, a struggling economy has highlighted the class tensions Americans themselves face, despite being far removed from Edwardian Britain — showing them that perhaps they have more in common with the show's characters than they originally thought.

The show is appealing, then, in two seemingly incompatible ways. It is an escapist pleasure at a time when there is much to escape from. At the same time, though, it highlights the very things from which we are trying to escape.

And Downton has brought a host of younger viewers to PBS, a channel traditionally associated with an older audience. It is a chance to see the British class system, with which Americans have historically been fascinated, in action, or at least a fictional representation thereof. And it is a chance to forget, for a moment, about student loan payments, health insurance or worries for the future. It is a chance visit another world, to see our problems played out by others, knowing full well that in the end, the characters will get their happily ever after.