- Utah's SB241 proposes holding back third graders not meeting reading standards.

- Sen. Ann Millner, R-Ogden, sponsors the bill, emphasizing early literacy and intervention plans.

- A Deseret News poll shows 67% of Utahns support the retention proposal.

SALT LAKE CITY — Third grade is a defining period in a child's educational development. Many say it's that pivotal academic year when a young student shifts from "learning to read" to "reading to learn."

And if a third grader is struggling to read, future classroom troubles are distinct possibilities.

Now in the wake of a recent report revealing about half of Utah's K-3 students are reading below minimum proficiency levels, many civic leaders, including Utah Gov. Spencer Cox, are calling for action.

Counted among the proposed strategies to boost early education literacy is one likely to split opinions: requiring a student to repeat third grade if he or she isn't meeting minimum standards.

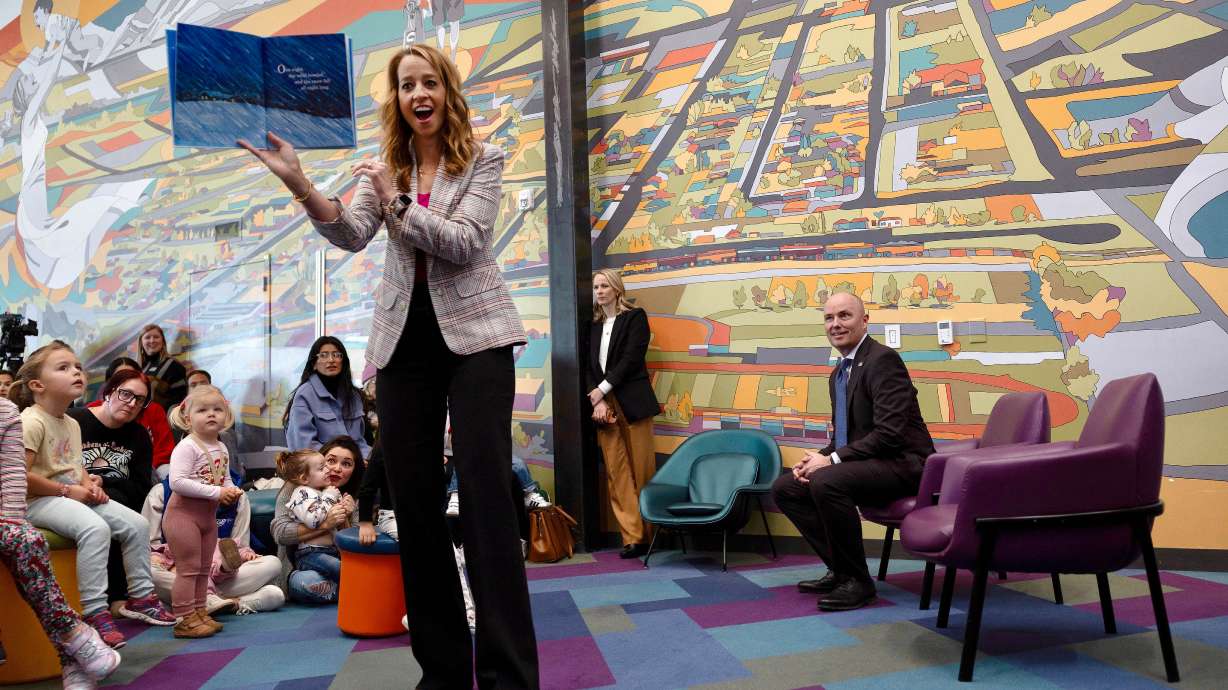

Now an early literacy bill sponsored by veteran lawmaker/educator Sen. Ann Millner, R-Ogden, is in front of the Utah Legislature.

Included in the interventions proposed in SB241 is a provision requiring struggling third graders to repeat a year — "except in cases of certain good cause exemption."

If SB241 becomes Utah law, it won't be unprecedented. Much of it mirrors policies behind the "Mississippi Miracle," which took the Magnolia State from the bottom of national elementary literacy rankings to the top 10 over the past decade.

Boosting K-3 literacy: An 'Early Literacy' measure

Speaking with the Deseret News, Millner noted the link between "reading well" and "living well."

"We need to have our kids reading at grade level at the end of third grade to give them the best opportunity to succeed — both in high school and, I think, in life."

A former Weber State University president, Millner has prioritized early literacy during her years on Utah's Capitol Hill. In 2022, she sponsored a literacy initiative to enhance strategies to improve reading among Utah's K-3 students.

That bill included increased resources to train K-3 teachers to best apply "the theory of the science of reading and helping kids learn." And she's worked closely with reading experts and educators, even while studying what's been done in Mississippi.

But those early literacy improvements, said Millner, are not progressing "as fast as we had hoped." That's prompted Cox and others to call for accelerations such as SB241.

Related:

Millner salutes the ongoing efforts of Utah teachers to teach their young students to learn to read. But SB241 would call for more interventions "to help our students and help our parents."

If ratified, the bill would require local education agencies to craft individualized reading plans for K-3 students not meeting reading benchmarks. Those individual plans would include working with parents, while also identifying and providing interventions. Strategies might include providing struggling students with more opportunities to work with trained paraprofessionals.

"The focus is on teachers, working with members of the schools, working with parents, developing reading plans and helping every student succeed at every level," said Millner.

"We start working with them in kindergarten, and then in first grade, and then in second grade, and then in third grade."

Incorporating 'the science of reading'

Also included in SB241 is a provision for teacher and paraprofessional training on the "science of reading." Millner points to "significant research" demonstrating the most effective teaching methods to help young students learn to read.

"We want to make sure we're using evidence-based pedagogy to help students learn to read. We have to train our teachers, and we have to provide support for our teachers in terms of applying that."

That's an ongoing journey that demands flexibility, she added.

Cox has called for additional paraprofessionals in Utah schools, and SB241 requests $15 million to go toward such reading specialists.

"That would not get (paraprofessionals) in every schoolroom, but it would help get them in the schoolrooms where there are more kids that need more assistance," said Millner.

Why hold a third-grader back a year?

While SB241 would, in general, require schools to hold a struggling third-grader back a year, "My goal is for no student to be held back from going from third grade to fourth grade," said Millner.

The bill's retention provision serves to increase focus on early literacy and reading benchmarks, beginning in kindergarten and continuing each year through third grade, she added.

"If we put the right reading and intervention plans in place, we should be able to get every student there and not have to retain any student.

"But this helps us focus."

Automatically moving third graders into fourth grade — including those who severely struggle with reading — only foreshadows academic troubles ahead, she added.

"If we haven't helped give those students the skills they need, they're going to struggle," said Millner. "So let's try to help them learn to read so they can succeed at learning history and science and math and all of the other content areas that they're going to increasingly see through their upper-elementary, junior high and high school career."

It's Millner's hope that her bill prompts principals, teachers, students, parents and communities to make early literacy "a real priority."

"We have to ensure (third graders) can read, because it's so foundational to everything else that comes with what we want our students to learn."

Millner recognizes that a state-mandated third grade retention policy could prompt fears. Some will likely ask how a third grader will respond to being held back a year while his or her classmates advance.

In some cases, she added, holding a child back a year might work best in kindergarten or first grade.

Millner also noted that the bill includes several "good cause" factors that would allow a struggling third-grader to move on to fourth grade. "But when we do that, we have to do it with intensive reading plans — and the parent will be in those conversations with the school."

Responses to third grade retention

A recent Deseret News/Hinckley Institute of Politics poll suggests Utahns would generally support a proposed policy requiring third graders who don't pass a state reading test to repeat the grade.

Slightly more than two-thirds of respondents — 67% — support the proposal, with 24% saying they "strongly support" it and 43% answering "somewhat support."

Meanwhile, 17% "somewhat oppose" and 7% "strongly oppose" a third grade retention policy.

The gap between those who support and those who oppose a third grade retention policy is a bit tighter for Utah parents included in the poll.

Fifty-nine percent of parents support it — with 19% responding "strongly support." Just under a third of parents voiced opposition to the proposed policy, with 8% saying they "strongly oppose."

Among Republican and Democratic respondents, 73% of Republicans expressed some level of support for a third grade retention policy. Democrats are slightly less on board, with 66% expressing support.

Cox has said there are ways to retain struggling third graders "with dignity and respect" — but adds, "We need that pressure.

"It's not that we want to hold kids back, it's that we want them reading at third grade level so we don't have to hold them back."

My goal is for no student to be held back from going from third grade to fourth grade.

–Sen. Ann Millner, R-Ogden

Expect SB241 to face some pushback when it's presented to lawmakers.

Sen. Kathleen Riebe, D-Cottonwood Heights, a career public school educator, told the Deseret News that there's not a lot of research demonstrating retention is a good idea.

"It's very traumatic for a student to be left behind," she added.

Riebe also worries about the costs that Utah third grade classrooms might have to absorb by adding retained students to their class rolls. "With all the money that we would have to invest in that third grade explosion, we could invest it more wisely, so that kids weren't being negatively impacted socially by having that retention."

Early elementary students, she added, would be better served by providing them with more resources "at a more precise level," such as after-school and summer school programs.