Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

- BYU study finds sugar-sweetened beverages increase Type 2 diabetes risk by 25%.

- Solid sugars, paired with fat, fiber or protein, show no significant diabetes risk.

- Researcher suggests public health guidelines should differentiate between liquid and solid sugar sources.

PROVO — A new study out of Brigham Young University finds sugar consumption through beverages increases the risk of Type 2 diabetes, while moderate amounts of other dietary sugars had no association with Type 2 diabetes or even lowered risk.

These findings prove that the impact of sugar in the body depends not only on the amount, but also on how it is delivered, according to Karen Della Corte, assistant professor of nutritional science at BYU and lead author of the study. She explained that the study shows the association between sugar intake and health is not as simple as commonly believed.

"Sugar has become a kind of nutritional villain, and there's a lot of public confusion surrounding sugar in the diet," said Della Corte. "The basic assumption is that sugar is bad for you ... but the truth is more nuanced than that."

Survey findings

Researchers from BYU, in collaboration with researchers at two German universities, conducted a comprehensive meta-analysis to demonstrate the dose-response relationship between dietary sugar intake and the risk of Type 2 diabetes. The study is one of the largest meta-analyses of its kind, according to BYU, and is the first to establish that dose-response relationship and challenge the assumption that all sugars equally elevate diabetes risk.

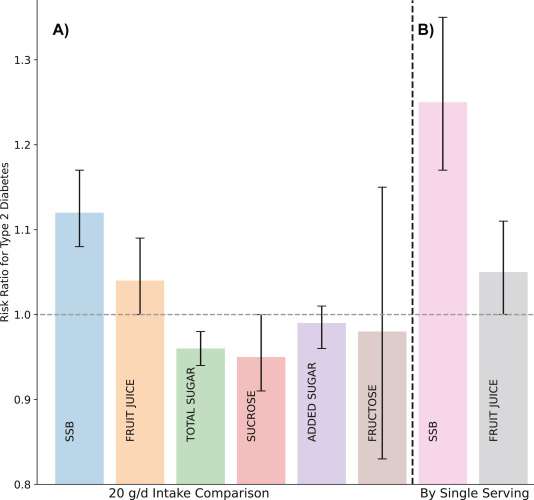

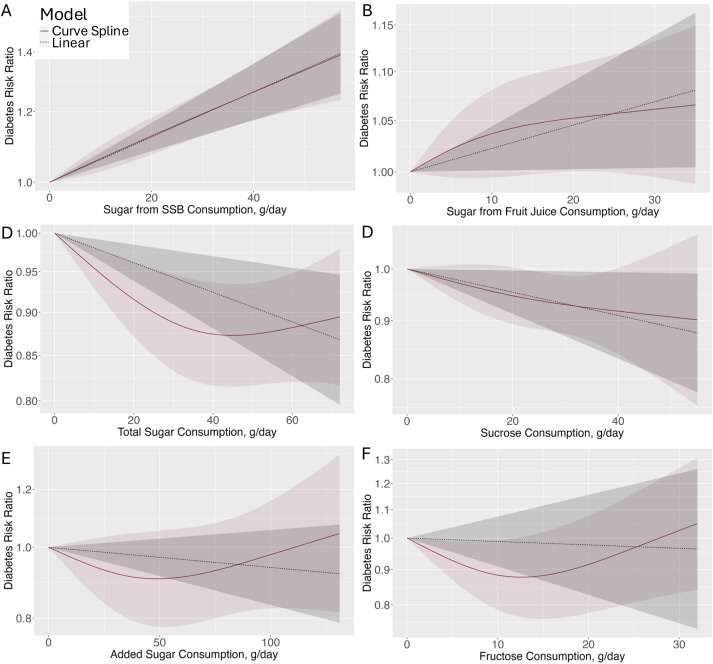

They found that with each additional serving of a sugar-sweetened beverage per day — such as nondiet soda, energy drinks or any beverage with added sugar — there was a 25% increase in the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes. When compared to other methods of consuming the same amount of sugar, sugar-sweetened beverages were associated with the greatest risk. Researchers also found that each additional serving of fruit juice per day increased the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes by 5%.

"Sugary drinks deliver large amounts of sugar quickly in isolated doses, without any of the components that normally slow down digestion, like fiber, protein or fat," explained Della Corte. "So when sugar is dissolved in liquid, it floods the system fast, and this rapid delivery can overwhelm the body's ability to process it in a healthy way."

Other sources of sugar consumption observed in the meta-analysis were shown to either have no significant association or were associated with a "significant reduction" in Type 2 diabetes risk, according to the study results.

An additional intake of 20 grams of sucrose, or table sugar, and total sugar, meaning naturally occurring and added sugar, per day, was associated with a reduction of Type 2 diabetes risk. Total sugar intake was associated with decreased risk for around 40 to 60 grams per day, but the risk plateaued and slightly increased when more than 60 grams were consumed daily.

Added sugar and fructose, a naturally occurring sugar found in fruit and honey, were shown to have no association with Type 2 diabetes risk when increasing intake by 20 grams per day.

'The modern food environment'

While sugar may get a bad rap, Della Corte believes her team's findings demonstrate that completely cutting out sugar is not the answer; changing the way we consume it is.

"The human diet has contained sugar for thousands of years, whether it was from fruits or honey or dairy," said Della Corte. "Sugar has always been a part of our diets ... it's not sugar itself that is new or somehow problematic, but the modern food environment. Today, we're consuming sugar in highly processed, isolated forms — often in liquid form, without any of the beneficial nutrients that typically accompany it in whole foods. And that's where the health risks really start to emerge."

The difference between the impact of liquid and solid sugars comes down to how the body metabolizes them during digestion, according to Della Corte. Sugar is absorbed more slowly when paired with fiber, fat or protein because it takes more time and energy to digest than a liquid. Liquid sugars pass through the stomach faster, allowing quicker absorption that causes blood sugar levels to spike and requires more insulin to metabolize.

Sugary drinks also often contain high fructose corn syrup, a type of fructose that is mostly metabolized in the liver. When consumed in high quantities, this causes strain on the liver and gets diverted to fat production, which can lead to metabolic issues like nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and Type 2 diabetes.

Nearly 12% of the U.S. population has diabetes — 23% of whom are undiagnosed — and 38% of American adults have prediabetes, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's National Diabetes Statistics Report. Reducing the public health burden of the diabetes epidemic has become a global health priority, according to Della Corte, which is why having more accurate information about what leads to the chronic disease and correcting misinformation is so important.

"Rates of Type 2 diabetes are increasing alarmingly, and when it comes to understanding how to prevent this, we need to understand what role specific types of carbohydrates play," said Della Corte. "We need to move beyond lumping all sugars together, as if sugar is uniformly harmful in all contexts. This study shows that sugars from beverages pose a clear risk, but sugars from solid, fiber-rich foods do not, and so public health guidelines should really reflect that nuance so we can target the sources of sugar that matter most."

Death to the 'dirty' soda?

While Utah is becoming increasingly popular in the media for being the home of the "dirty soda" — which typically involves adding sugary flavored syrups to regular or diet soda — Della Corte hopes people will be more aware of the health impacts when consuming these sweetened drinks.

"The thing about sugary beverages is they don't have any impact on satiety," she said. "So, compared to solid sugars, when you consume the same amount alongside other foods, it triggers a satiety effect, and you eat less later in the day. Whereas if it's in a liquid form, it just usually goes on top of whatever you're eating, and you get no signal that somehow you've consumed energy. So it just adds excess calories, but it's also a harmful form of calories."

Sugar has always been a part of our diets ... it's not sugar itself that is new or somehow problematic, but the modern food environment.

–Della Corte

While the study did not include research on artificial sweeteners, Della Corte says diet beverages should not be seen as health-promoting but may be a beneficial tool for transitioning from sweetened beverages. She recommends drinking sparkling water, naturally flavored drinks or water infused with fruit or herbs as the best replacements for sugary beverages.

As for other foods, Della Corte says eating sugar with dairy products like yogurt, fiber-containing cereals or whole grains has no link to diabetes risk and can even help people have a healthier diet overall.

"Having sugar in your diet, there is really a place for it. It can be part of a healthy diet, and it can actually increase the likelihood that you will consume nutrient-dense foods. If it's more likely you're going to be consuming whole grains because sugar is added to it, that's a good thing. Our findings suggest that we need more nuance, public health messages should move beyond 'just cut sugar.'"

Della Corte's next project will involve comparing sugar-containing food sources and foods with a higher glycemic index, specifically those containing carbohydrates that raise blood sugar levels more rapidly than others. This research may help people identify suitable substitutes for foods associated with an increased risk of Type 2 diabetes.