Estimated read time: 11-12 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This is the second story in a series highlighting Season 2 of the KSL podcast "The Letter." This season explores topics like grief and forgiveness, but under very different circumstances. The podcast explores what happened after two young fathers were murdered outside an iconic Utah restaurant in 1982. The families struggle to rebuild and have to wrestle with questions that take decades to answer. Does everyone deserve forgiveness? Does it matter if there is no remorse? And if trauma can be passed through generations, can forgiveness also be passed down?

SALT LAKE CITY — Carla Maas pulled to a stop in front of the Salt Lake laundry company where her husband worked. She turned off her car, and almost immediately, someone came out of the front door.

But when she looked up, it wasn't her husband, Buddy Booth.

It was her husband's boss.

"And I used to work for Peerless so I thought he was just coming out to give me a hard time," she said.

But then she noticed there was something odd about his demeanor. She rolled down her window.

"And I said, 'What do you want?'" she said looking down. "That's when he told me that Buddy had been shot."

Without thinking, Maas fumbled for her keys, still hanging from the ignition. She needed to get to her husband.

"I tried to start the car, because I was gonna go … where he was," she said. "I was quite hysterical. ... His boss reached in and grabbed my hand and took the keys. He said, 'Carla, it won't do you any good. He's dead.'"

Maas said she thinks she went into shock. She remembers screaming and crying, but she's not sure how much time passed before her brother-in-law pulled up next to her car.

"They opened the door for me to get out, and I couldn't move," she recalled. "I couldn't feel my legs. … I could feel my hands, my arms, but I couldn't move. So they had to help me out of the car. Wow. … I was numb. I was just totally numb."

They drove her to their house, and they insisted she and the girls stay with them. She was reeling, heartbroken, terrified.

She was 23 and now a widow.

How could she pick up the pieces of a life that already felt so fragile?

A rough start

For Maas, life had always been a challenge, something she needed to wrestle into submission.

The 12th of 13 children in a blended family, her parents divorced when she was so young, she has no memories of their marriage. She had almost no relationship with her biological father … until she went to live with him at age 12.

"I was kind of a brat and didn't want to live at my mom and stepdad's house anymore," she said. "And so they sent me to my dad's. And I was thinking it would be better there, but it was worse."

Her parents' attempts to discipline or care for her felt like a cage she had to escape. She skipped school, ran away from home oftentimes with boys, until eventually, it landed her in juvenile lockup.

"They call it ungovernable," she said of what she was like as a child. "I didn't want to listen. I wanted to basically be on my own. … I didn't want to feel like my parents owned me."

Childhood held no allure for her. So when her caseworker suggested she get permission from the juvenile courts to be considered an adult, she agreed.

"It continued until I was 16," she said. "And then I was emancipated from my parents."

She dropped out of high school, moved in with a friend, and started to live life on her terms. But that turned out to be a lot tougher than she had anticipated.

She was just 17 when Buddy Booth and his cousin walked into the all-night diner where she was eking out a living. He was 19, hardworking, and he seemed smitten right away.

"They chose to sit at the counter," she said. "And I was waiting on him. … Buddy was talking to me. And I just felt flattered because not too many people, you know, guys, said a word to me. They didn't even notice me, a lot of them. And so I got talking to Buddy. … He was really sweet, and two weeks later, we moved in together."

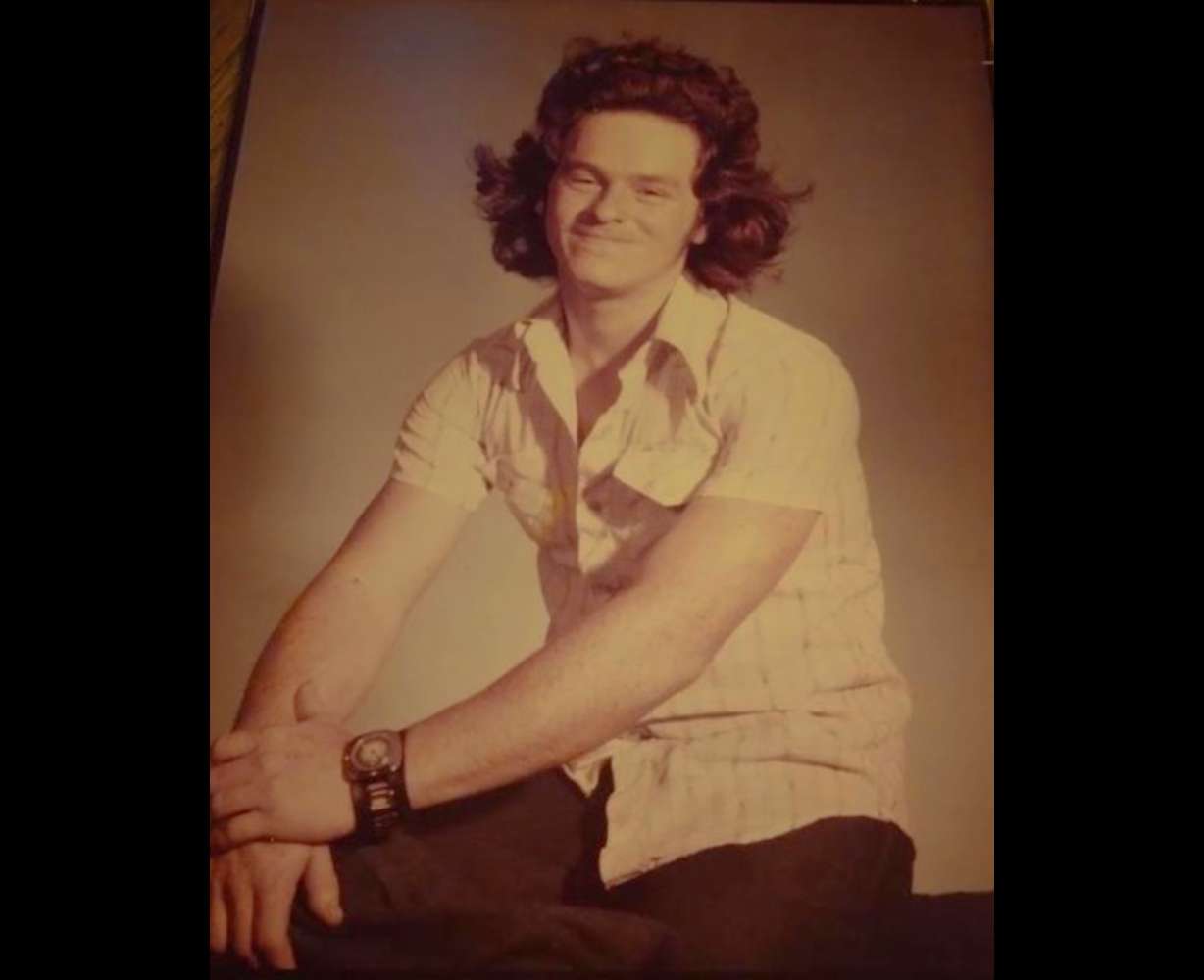

She said Booth was handsome but not in the traditional sense.

"Buddy had red curly hair — really thick, red curly hair," she said. "He had freckles. And, he was a little bit taller than me (about 5 feet 3 inches)."

Oh, and one more thing, she said. He was missing all his front teeth.

"He had been hit in the mouth with brass knuckles," she said, giggling. "It didn't matter to me; it didn't bother me a bit."

She liked his unconventional looks. But more than that, she liked who he was.

"I don't fall for someone who's perfect and glamorous and all that stuff," she said. "I fell for the kindness, the caring."

The two had a lot in common. He also grew up in a blended family. He was the fifth of eight children — 14 if you count half-siblings. And he offered Maas the same thing he'd given his mom and siblings growing up — someone they could rely on.

Booth's younger sister, Tamie Pipes, said he was the one they all relied on, especially after their mother remarried an alcoholic when he was a teen. Despite losing his childhood to other people's decisions, he was a happy, playful big brother. Pipes said he played cards, loved music, and made sure his siblings did what they were supposed to do.

Oh, and those teeth he was missing, Pipes said he lost those to an infection when he was a child. But in his defense, it did sound more impressive to lose them in a fight than to an inability to get health care.

A great dad

Maas found out she was pregnant just a few months after they moved in together. She was only 18, and he was 19, but Booth wanted to get married right away. She refused.

"I didn't want a child to be the reason we got married," Maas said.

But after the birth of their daughter, Norma, she agreed to get married. Booth wore all white, and she wore her sister's yellow dress adorned with small flowers.

"It was so pretty," she said. "We were happy."

But even their best days were hard. Baby Norma was born with a heart defect, so she spent the first few weeks of her life at the hospital. Booth couldn't take time off work, but he spent every minute he could at her bedside.

"We were young parents, and it was so scary," she said. "And it was tough on him because he always worried about her. … She became his everything."

Despite the fear and worry of those first weeks, which included an open-heart surgery, Booth embraced fatherhood.

"When he'd come home from work, he'd play with her on the floor," Maas said. "They would just have fun with each other. … I loved seeing the two of them interact with each other. It was beautiful."

She pauses to wipe her eyes.

"Buddy was a great dad."

Stormy marriage

When it came to their marriage, however, there was more turmoil. They fought often, and it only got worse after Norma's birth. Eventually, Maas decided they needed to separate.

"I left him and took Norma," she said. "And he was not happy with that one. … He wanted Norma."

Their arguments shifted to his access to his daughter. And eventually, it escalated to a fight in a parking lot. A stranger called the police, and Norma ended up in foster care while they had to take classes on parenting and see a family counselor. Their daughter was in state custody for around eight months.

"It was terrifying," Maas said.

But they took the classes and rekindled their desire to make their marriage work. She moved back to their apartment, and they learned they were expecting a second child. About a month after little Dana was born, Norma came home.

They were, once again, a family. But they'd only have three months together before that snowy March morning in 1982.

When Maas woke up, she saw the snow, and the sense of dread she'd been feeling exploded into panic.

"I just had a feeling something was gonna happen," she said. "I just had this feeling several days before, and it just kept getting stronger and stronger."

She begged her husband to stay home, but he was already dressed and running a comb through his thick, unruly curls. The 24-year-old father of two sleeping little girls shrugged off her worries.

"But I knew something's wrong," she said.

Still, she also knew that if there was one thing Booth was, it was reliable. He never missed work. So she pulled on her coat and drove him downtown to Peerless Laundry.

As she dropped him off, she thought about the fear she felt in her gut. But she was also hopeful. Their problems weren't solved; but they felt a new sense of commitment, not just to each other, but to their daughters.

They were young — just 23 and 24 — and if there was one thing they thought they had in abundance, it was time.

A man with a gun

Booth climbed into his Chevrolet delivery van undaunted by the weather, with 27 cents and his favorite comb in his pocket. He enjoyed his job and the people he met along the way. The sun was just rising as he turned onto Millcreek Canyon Road.

As he eased the van up the snow-covered driveway at Log Haven restaurant, he noticed another car already outside. It was a Jeep, and the doors were still open. As he got closer, he could see something in the snow.

Then he realized it wasn't a thing, it was a person.

According to police reports, he stepped out of the van, his boots sinking into the unplowed snow. He approached the person and realized it was a man laying face down in the snow. There was blood everywhere, but just as he leaned over the body, someone came rushing out of the restaurant. Booth spun around and came face to face with a man about his age.

"What happened here?" Booth asked.

The man said something, but Booth wasn't looking at the man anymore. He was looking at the gun that the man was pointing at him.

Booth turned to run just as shots rang out.

'Looks like murder'

"They are both dead."

That's the first thing a Salt Lake County paramedic told deputy Mike Wilkinson when he arrived at Log Haven around 8:15 a.m. on March 5, 1982. Before Wilkinson could react, the paramedic added: "Looks like murder. They are shot."

The rescue crew stood near a laundry van that was parked on the side of the canyon road in front of the restaurant. The back doors of the van were open, and Wilkinson could see two bodies lying face down. One dressed in black suit pants, a gray jacket and black oxford shoes. The other wore brown pants, brown hunting boots, and a blue jacket — a blue comb stuck out of his left rear pocket.

And then the paramedics pointed at a man standing near them. It was him, they told Wilkinson, who'd found the bodies and called the police.

The man was the restaurant's manager, Michael Moore. He was young, thin, his curly dark hair cut short, and he wore a plaid shirt tucked neatly into his jeans.

"Mr. Moore appeared quite shaken, and I had him sit in my patrol car," Wilkinson wrote in his report in 1982. "I asked him if he knew the victims, and he said he thought one was Jordan Rasmussen, the auditor for the owners of Log Haven. He said Jordan's auto was parked at the mouth of the canyon, that he had passed it coming up. He also said he had a meeting scheduled with Jordan at 8:00. He then stated he needed a drink of water, could he go up to the restaurant. He exited the car and walked up to the driveway going up to the restaurant."

As he got out of the car, a firefighter approached him.

"One of the firemen asked me if I had noticed the blood on that guy's face," the report said.

Wilkinson had not noticed any blood.

He headed toward the restaurant. When he got inside, he asked Moore, who was holding a napkin, to sit at a table with him. As he sat down, Wilkinson saw blood stains on both knees of his jeans. But there wasn't blood on his face.

He said Moore was agitated, rambling.

"He was talking about business problems," the report said. "It's all crazy. … They set up people. ... They're going to fire us all."

Wilkinson said he wasn't sure what happened, but he was certain of one thing. He needed to keep this young man with him until detectives arrived.

Once homicide detectives came, they decided to take Moore downtown to their offices. It would take two interviews, but by 5:30 p.m. that evening, Moore confessed to killing both men.

But his story baffled investigators. And they wouldn't be alone. Even Moore's defense team would find his story confusing.

As one prosecutor put it, "It just didn't add up."

Follow for free on your favorite podcast app or at theletterpodcast.com. You can subscribe on Apple Podcasts for exclusive bonus content, available with each new episode on Tuesdays.