Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Jared Wright understands why there's a lot of "passion" and "concern" regarding the future of West High School.

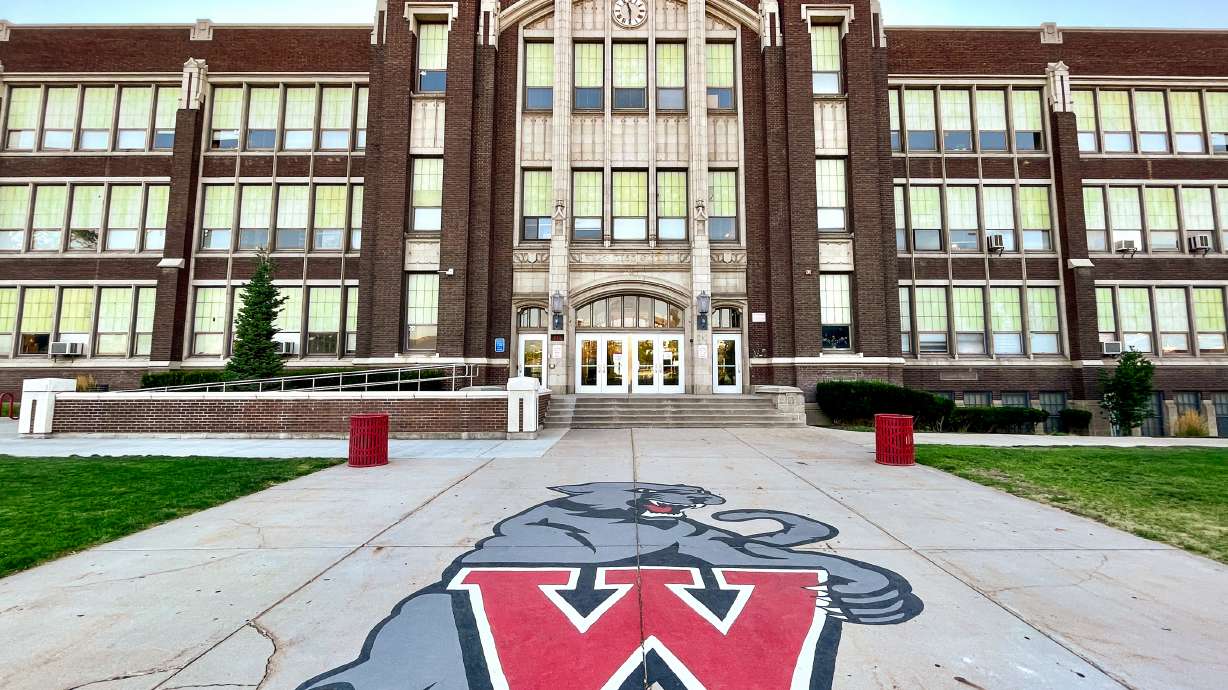

As an alumnus who landed an early teaching job there, the now century-old West High School building means a lot to Wright. Then, he became the principal of the school in 2020 and his view of the building slowly changed.

"I love this school like an old friend — this building. (But) coming in as a principal a few years ago, my perspective changed, as far as looking at the functionality of the high school, as it relates to serving the needs of our 21st-century students," he said, as he stood on the stage of the school's auditorium Wednesday evening.

Growing issues with the building, which was completed 100 years ago this summer, are why Salt Lake City School District leaders are now beginning an architecture feasibility study to "reimagine" the West High campus, which may include a full rebuild of the school. A similar study is also being launched for the 66-year-old Highland High School, which may also be rebuilt in the future.

It's unclear yet what the future is for either building. The feasibility studies, district officials say, will ultimately determine everything from what's needed to improve each school to the estimated cost of any projects.

"We don't have a plan right now. We have a completely blank piece of paper and we're just starting from scratch," said Paul Schulte, the executive director of auxiliary services for the Salt Lake City School District, adding that providing West High students with a "professional, modern (and) best instructional space possible" will take top priority and that any decision will honor the school's "rich and respected heritage" after that.

Whitney Ward, a principal at VCBO Architecture, the firm the school district hired to conduct the West High study, said the document should be completed in the winter. It will take in "a ton of information," including community input from students and alumni, she said.

The district brought in the firm Naylor Wentworth Lund Architects for the Highland High School study. Philip Wentworth, the firm's vice president, said his team will have the same deadline, adding the feasibility study will also determine how any project is completed, such as the possibility of building while school is in session in the future.

Once complete, the studies will dictate how much the district will request in the form of a bond to cover the cost of any potential projects, which Salt Lake City residents will ultimately vote on. The district is currently planning to have a bond proposal ready next year in time for it to be placed on the 2023 ballot.

"This is going to be a long journey," said Highland principal Jeremy Chatterton, during an event on Thursday. "This is simply the first step."

Balancing new needs and legacy

West High School has a rich tradition in Utah because it's the state's oldest high school, as it was founded in 1890. However, it wasn't in the building that the school uses today. After nearly three decades at another facility, the Class of 1919 helped a campaign for a bond to create the building that people now associate with West High School.

That said, there have been eight building additions since 1959 that have helped account for the growth in the student population over the past century. The last of those came through a pair of projects in 2011. The building also went through a multimillion dollar seismic retrofit in the 1990s, according to the Deseret News.

"The Salt Lake City School District has done a ton of stuff over the years to maintain the campus and to keep it meeting those students' needs," said Alex Booth, another principal at VCBO Architecture. "I mean no other school in the valley has lasted 100 years."

Even with those efforts, he and other members of the firm went over the school's growing "unique challenges" and deficiencies tied to the original building and its additions. For example, every addition features different architectural styles so they have to be treated differently.

There are also classroom and hallway size issues, as well as accessibility issues in some of the rooms. Mechanical systems issues mean that the school can be both difficult and expensive to operate. Meanwhile, the school has 13 different entryways and none of them are very secure, said Brian Peterson, another principal at VCBO Architecture.

"Building a high school is really difficult to keep it locked and safe but one of our jobs, as your architect, is to design a building that feels open and inviting but also gives us an environment where we can close it down quickly," he said. "Unfortunately, right now, we don't have that at West."

Yandary Chatwin, the school district's spokeswoman, said Highland High School has somewhat similar issues, especially when it comes to the student population. She said the school principal's office is the only open space available for meetings. All the original conference meeting spaces had to be turned into classroom spaces to accommodate the growth in population.

"There's literally no more room at Highland High School," she said, of the building that opened in 1956. "They've gotten creative with the space they've got and it's time to make sure that we're providing the best experience for these kids because they deserve it."

Yet given all the history both schools have, it's hard to let go. The feasibility studies caught the attention of some alumni and history groups that hope there is an option that can preserve as much of the school's past while still offering children opportunities to succeed.

David Amott, the executive director of Preservation Utah, attended Wednesday's meeting to listen in. He told KSL.com afterward that he appreciated that the district and architecture firm acknowledged West High's importance in the city and that he "understands and sympathizes" with the school's current struggles. But he also didn't believe the presentation offered any insight into all the possibilities to renovate the building into something that fits the needs of students.

"You can have an old building and still have something that works in 2022 or beyond," he said, noting many old buildings even in Salt Lake City that have been remodeled for tech startups. "What I heard was really a dichotomy, a black-and-white, hot-and-cold type of argument. ... You can have a building that is as historic and full of heritage as West High and still trains people for something other than working in a factory in the sort that they presented."

Neither school is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, which can offer tax credits that go toward projects that renovate any building 50 years or older, as long as they fit historical merits. Schulte said, that at least with West High, he is "very confident" that it would cost "significantly" more to maintain the school in the future than to replace it, though he said the feasibility will answer if that's true or not.

Ward explained that the estimates in the study will include the "life-cycle costs," which factor in the cost of when parts of a building start to fail in addition to reviewing the cost to demolish and rebuild the school. A similar process is expected for Highland High.

Still, Amott said hopes both buildings can be "adaptively reused" in the future instead of them being torn down because of their meaning in Salt Lake City. Ward acknowledged Wednesday that history is what makes the West High project particularly different, calling it "not your typical high school" because of its long legacy.

"There are generations of students and alumni who (view) West High as an important piece of their personal life and experiences," she said. "We also know it's a strong part of the Salt Lake City community, so we want to make sure we're engaging with not only the current students but also future students ... and alumni networks."

The same can be said of Highland, Schulte adds.

The next steps forward

The emotion from both sides of the issue may ultimately prove to be beneficial. Chatwin said she believes it has the power to drive community input, which is what the district wants out of the feasibility study process. The point of the current process, she said, is to include as many voices as possible to ensure any project matches what the community wants with what current and future students need.

"There's a lot of tradition and it means a lot in this community but I know something else that means a lot to the community is the educational experience of our students," she said.

In the meantime, people can participate in the process by filling out the district's online surveys. The studies are expected to be completed by Feburary before the next steps are announced.

Chatwin said there is no real timeline for when construction could begin at either school because the studies need to be completed for a cost estimate, which will determine how much is needed in bonds. If the district puts a resident for a bond on the 2023 ballot, residents will need to approve it before any project comes to fruition, too.

"We're on a path together. Right now, we're gathering," Wentworth said. "We want to hear from you. We want to make sure that we understand what it is that needs be in the school. We'll be working on concepts pretty quickly here with the time we have."