Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

OGDEN — A Utah Highway Patrol trooper was traveling on the I-215 West Belt in Salt Lake County on New Year's Day when the agency reported he came across an "interesting encounter."

A large pickup truck had collided with a great horned owl on the freeway, seriously injuring the bird. The trooper quickly decided to take the creature, affectionately called "Owlpacino," to the best place he thought it had for survival — the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah in Ogden.

Despite the efforts of the staff at the center, Owlpacino didn't survive the severe injuries, said Buz Marthaler, the co-founder and chairman of the center. But the story of Owlpacino is a perfect of example of the animal cases that the center receives on a regular basis since it was founded over a decade ago.

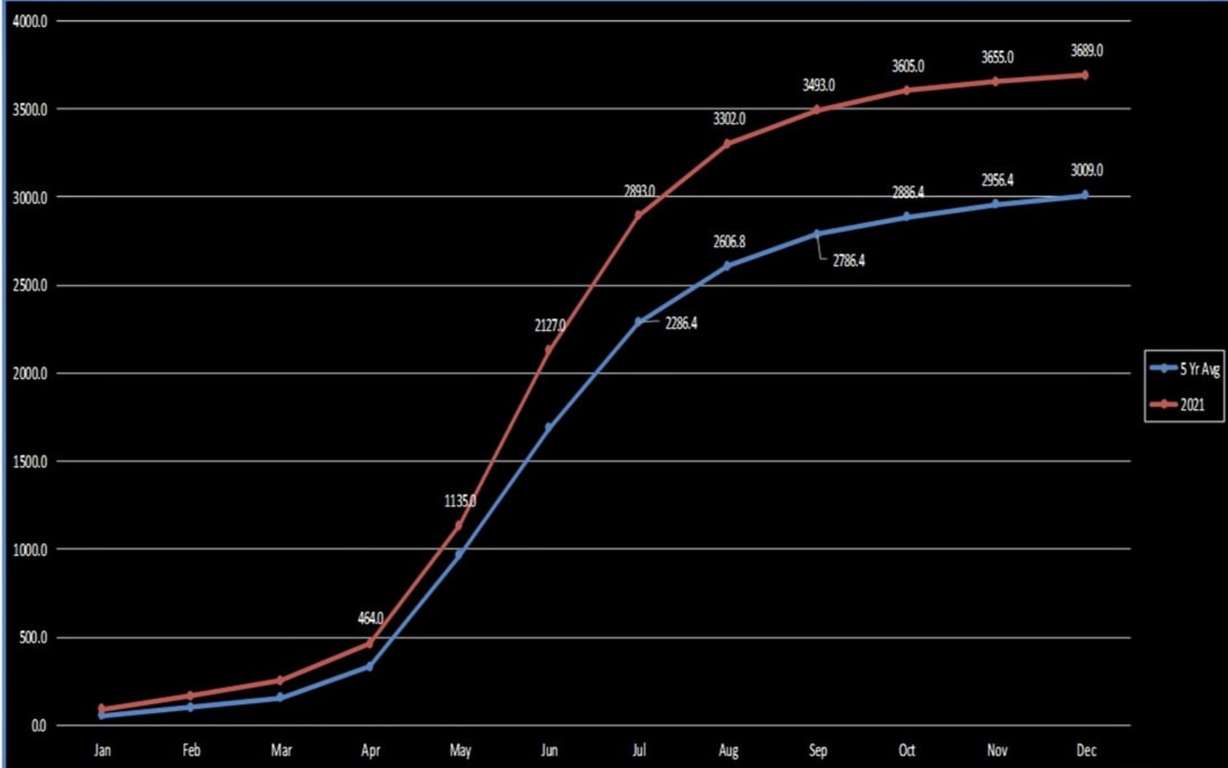

The nonprofit charity reported earlier this month that it received 3,689 sick, wounded or orphaned birds, reptiles and small mammals. These include raptors, waterfowl, songbirds, rabbits, squirrels and snakes.

Then there's "Bee," a young beaver kit that can be seen roaming around the center. Beavers are some of the larger creatures the center cares for because it's not licensed — nor big enough — to handle bigger mammals in Utah's wild, like deer, elk, bears or mountain lions.

The 2021 number of treated animals is 680 over the facility's five-year average for new animal patients. And that trend continues into the first month of this year with cases like Owlpacino.

Marthaler says the center generally sees an increase of new animal patients every year. For instance, it only dealt with a little over 1,500 patients in 2008 — about half the average between 2016 and 2020.

Utah's growing number of sick, injured or orphaned animals

There are actually several reasons for the center's rise in animals to treat, some of which are symbolic of issues statewide.

First, the center has become more recognizable through time. Salt Lake City Weekly named the center the "Best Apocalyptic Flock Support" last year in its annual "Best of Utah" awards because of the work it did throughout 2021. The center even made global headlines in 2019 after a drunk man came across an abandoned bird and used a rideshare app to send the bird to the center for treatment.

"People aren't just taking it into their own hands because they think there's nothing else out there," Marthaler said. "There are a lot of people on social media who know of us and recommend us, so we're getting more animals that are already out there injured."

The center also works in coordination with various agencies, including the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources. Faith Heaton Jolley, a spokeswoman for the agency, said there are many birds the division comes across in the region that end up going to the center because the staff there is better suited to handle them.

Then there's Utah's growth, which factors in in different ways. Utah's population jumped by over a million people in just two decades, and new housing developments, and even new cities, have taken shape on what used to be wildlands, in a relatively short amount of time.

That also results in more buildings and vehicles that birds and other animals can collide with — as in the case with Owlpacino earlier this month. More people also generally means more cats and dogs that interact with wildlife.

Population growth also means there are more people who can find sick or injured animals in the state that otherwise wouldn't be treated. The spike in people heading outdoors for recreation during the COVID-19 pandemic also ties into more people coming across sick and injured animals in the region that are then sent to the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah.

Every animal, from the mouse up to the eagle, were affected by (the drought) either directly or indirectly, whether by the heat itself or how it reduced the amount of food out there.

–Buz Marthaler,co-founder and chairman of the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah

Utah's climate was also a "huge" factor in the rise in new animal patients last year, Marthaler said.

2021 was the third-warmest year on record throughout Utah, and the state ended up with its warmest summer on record. Add in a persistent drought that hampered food opportunities for wild creatures — animals were exhausted and hungry — and it made it difficult for them to survive.

The drought impacted all sorts of animals. State wildlife biologists reported tens of thousands fewer deer in Utah because of the drought conditions ahead of last summer's record heat. However, the conditions essentially factored in all levels of the food chain, too.

"Every animal, from the mouse up to the eagle, were affected by this either directly or indirectly, whether by the heat itself or how it reduced the amount of food out there," Marthaler said.

Nearly six out of 10 animals treated last year arrived during the months of June, July and August, according to the center's data. There was an influx of young birds that had fallen from their nests during the sweltering heat.

Marthaler explained that many young birds would fall out of their nests because they just weren't strong enough to fly and get food. Since their parents would either prioritize the fallen bird's siblings still in the nest or because they won't feed a bird on the ground, people would then stumble across the injured or abandoned bird and it would end up at the center.

The center wasn't alone in dealing with thousands of wildlife last year. Jolley told KSL.com that the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources responded to 3,301 wildlife calls in 2021, although not all were injured animals. Some of those calls were a result of dead animals in roadways or wildlife that needed to be relocated. Some of the injured animals among those calls ended at the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah.

The number of animals seen by the state division, unlike the trends the center saw in 2021, was actually significantly less than the previous year. Jolley said the agency responded to 4,894 cases in 2020. She didn't specify how many of those cases were injured animals, dead animals or animals that needed to be relocated — or the different types of animals the cases were about.

How to help injured wildlife

All interactions with wildlife should be from afar. Marthaler recommends people view all smaller wildlife through binoculars or camera lenses if they want a closer look. That's no different from what the Utah Division of Wildlife Resources recommends for larger — and more dangerous — species.

But if someone does come across an animal that appears to be sick, injured or orphaned in Utah, there are options to help.

Call the experts first. State wildlife officials compiled a list of the dozens of local rehabilitators and nuisance control specialists that can be found across the state, including the Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah. If the injured animal may be the result of attempted poaching, people can also call the division at 1-800-662-3337.

Every organization may have a different way to handle a new case. The Wildlife Rehabilitation Center of Northern Utah, for example, says its experts can help determine if the animal in question actually needs assistance. Sometimes an animal looks sick, injured or abandoned but is actually healthy. They even have a flow chart of what to do for certain animals.

If the animal does need to be brought to the center for treatment, the experts will recommend the best way for that to be done. People shouldn't try to care for wild creatures on their own because it's unsafe and also illegal.

It's not uncommon for the center to field calls from residents who said they tried to take care of a wild animal but then aren't sure what to do after several months.

"We get them all the time," Marthaler said.

The animals handled this way usually can't be returned to the wild because they've become imprinted through human activity. Unless the animal can end up in a zoo or a similar type of facility, experts normally won't bring in those types of cases.

There is another way people can help even when they don't come across sick, injured or abandoned animals. Marthaler points out that the facility doesn't receive funding from the state, meaning it mostly relies on contributions.

Contributions have helped the center run for over a decade — and have helped it treat more animals.

"The only way we are here is through people donating," he said. "We can't survive without that. ... Even if we get a bald eagle in that's federally protected, that all on us to find money to be able to repair its broken wing or do whatever is required to get it back out into the wild."