Estimated read time: 18-19 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Sherry Munsell, 49, is no stranger to pain.

Her dad, who she called her best friend, died when she was a teenager. She said she was grazed by a bullet while she was serving as a sheriff's deputy in California in 2010, when one of her fellow officers was shot and killed. And since 2014, she's been battling breast cancer. That brought her to Utah in 2016 for treatment at the University of Utah's Huntsman Cancer Institute. Fortunately, over the past six month's she's been in remission.

But now, after moving to Utah amid her medical struggles and earning only $17 an hour as a truck driver, Munsell is dealing with a different kind of pain — a pain that thousands of other Utahns are facing just to keep a roof over their heads as wages stagnate and cost of living creeps up year after year after year: How do I pay my rent?

Upheaval from the COVID-19 pandemic last year slowed rates down slightly, but not for long. They're on track to continue to climb, housing experts say, especially as Utah's housing market remains red-hot with staggering sale prices and a highly competitive market.

Almost every year over the past decade, Utah's rental prices have shot up to the tune of 5% to 7% a year along the Wasatch Front, a startling reality that means the average Salt Lake County apartment that cost $793 in 2008 now costs about $1,145. In Utah County, the average apartment that cost $719 a month in 2008 now costs about $1,200.

A stunning 1 in 5 Utah renters are considered "severely cost-burdened," meaning they pay more than 50% of their income on rent, according to state and federal data.

When Munsell and her wife first moved into a three-bedroom, two-bathroom house in Clinton, about four years ago their rent cost $1,395. Now, it costs about $1,560 a month, including renter's insurance, Munsell said.

"It's like every time we turn around, it's going up," she said.

The cost of their rent eats up about half of both of their paychecks, Munsell said, meaning they fall in the 1 in 5 statistic of "severely cost-burdened" Utahns — a bracket that has higher risk of eviction, perhaps just a car breakdown, a medical emergency or a job loss away.

To Munsell, moving seems just as expensive as staying. And she said she can't qualify for a home right now because she's waiting for her $80,000 in student loans to be forgiven by the federal government, set to be finalized early next year. Maybe if she could eventually buy — perhaps something for $200,000 — she said she'd try to find an older, smaller one- or two-bedroom, but for now the three-bedroom Clinton house works for her, her wife and their three dogs: Bailey, Bella and Hope.

Paying rent frustrates Munsell, knowing that the money they've been paying for years could have been going toward an investment.

"It's hard," she said. "But you know what, I'm blessed to be alive. I've been through a lot. I've seen a lot."

Times have been especially tough lately. Munsell's wife Susan recently broke one of her ribs from a slip in the bathroom, and she said she's been out of work as she's healed.

"Without her making money, I'm really strapped right now," Munsell said, though she added she's grateful to have a brother and sister that sometimes helps her make payments if she starts falling behind.

"If we didn't have (their help), we would really, really struggle," she said.

To help make ends meet, Munsell said she sometimes gets food from a local food pantry. She also doesn't have internet or cable.

"We don't live a lavish lifestyle," she said, adding that while there is a car payment, she drives a truck that's over 10 years old. "We can't afford anything more. But we work hard — as much as we can."

Renting in Utah: A conundrum

For most renters, price hikes are a frustrating reality. They squeeze struggling families, seniors on fixed incomes, single moms working two jobs, and young professionals who are trying to live the lives they want — but are having to make hard choices that impact their futures, like putting off saving for a home purchase.

Utahns are getting priced out of desirable but more expensive areas like downtown Salt Lake City, Cottonwood Heights and Sandy. But rents are also continuing to rise in more affordable areas, too.

Utah renters are losing choices.

Consider:

- In the Salt Lake City metro area, the median cost of rent went from $1,384 a month in March of 2020, when the pandemic first hit home here, to $1,451 a month one year later, a 4.8% increase, according to a new report by Stessa.com. The site ranked Salt Lake City metro area No. 64 out of 105 U.S. cities where rents changed the most since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

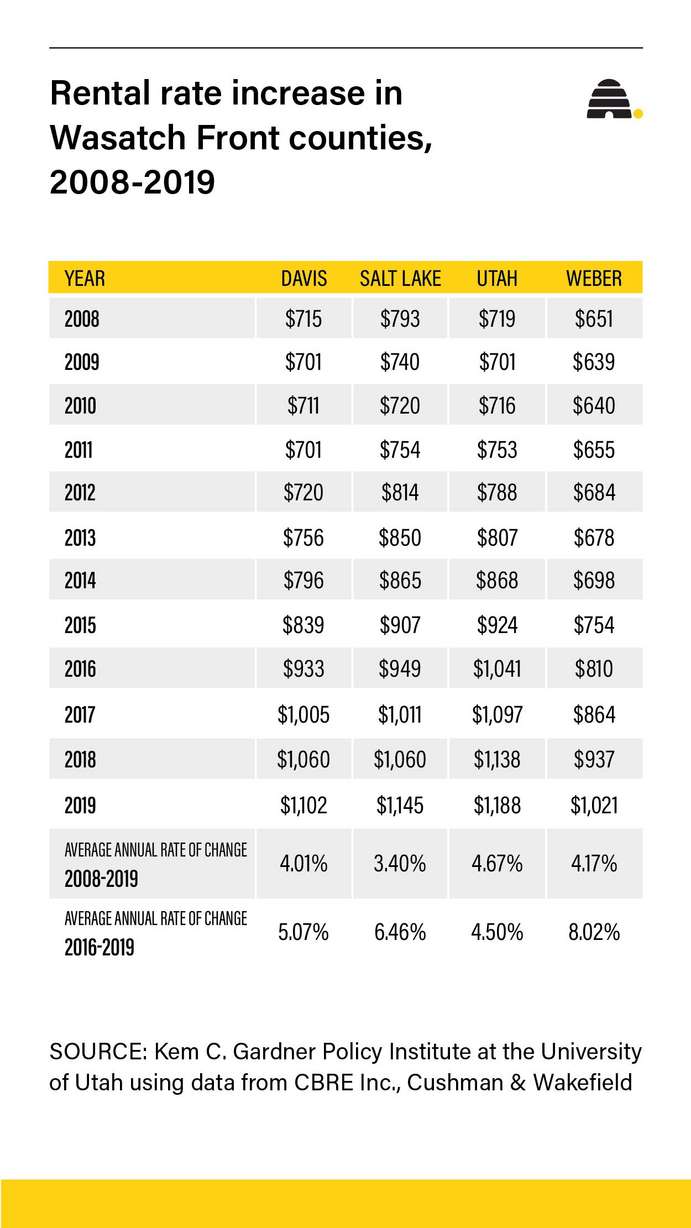

- Despite a record-setting apartment "boom" that's lasted for more than five years, rents across Wasatch Front counties have been increasing at an average of 5% to 7%, depending on the county, according to a November 2020 report from the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

- From 2000 to 2018, rent in Utah County rose a striking 83% — the highest increases of the Wasatch Front counties. Salt Lake County's rental rates rose 78%. Davis and Weber counties increased 64% and 59%, according to a June 2019 report from the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute.

- In 2008, Salt Lake County rents averaged $793. In 2019, that figure climbed to $1,145. In Utah County, rental rates went from $719 in 2008 to $1,188 in 2019. In Davis County, they climbed from $715 to $1,102. And in Weber County, rates went from $651 in 2008, to $1,021 in 2019, according to the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute's November 2020 report.

- Rents are outpacing wages and inflation. From 2000 to 2018, average rent in Salt Lake County was more than twice the rate of inflation. For example: In 2000, the average rent for an apartment was $647. If rent increased at the same rate as inflation, the average rent for an apartment in Salt Lake County would be approximately $850 in 2018, nearly $300 cheaper than the actual 2018 average, according the policy institute's June 2019 report.

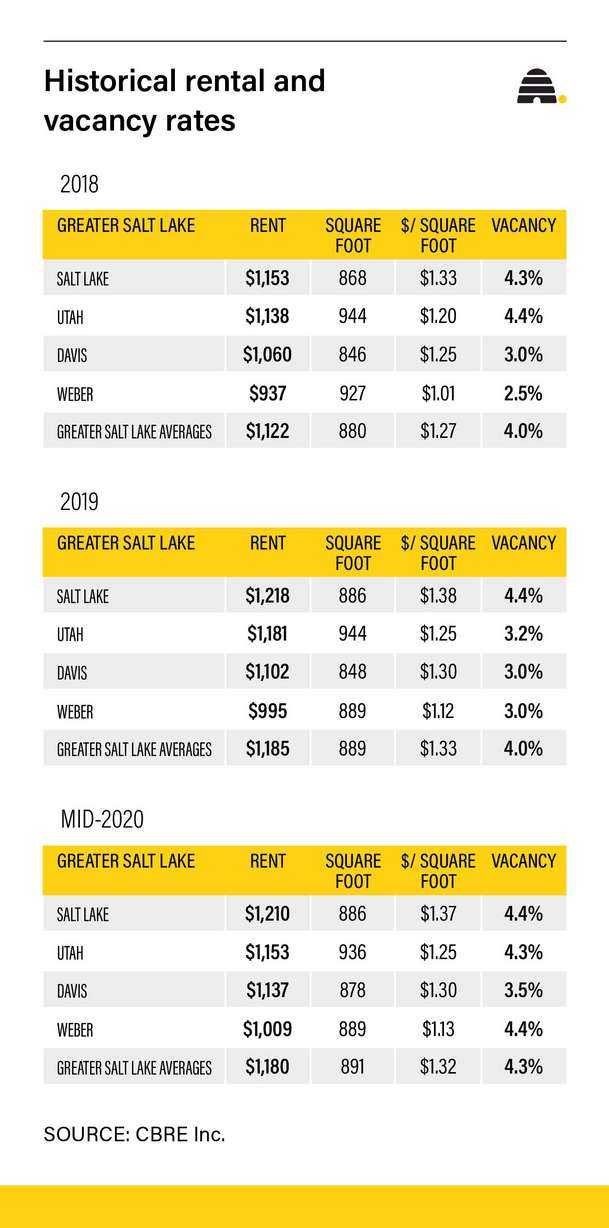

- Meanwhile, vacancy rates stay low. In Salt Lake County, vacancy rates have gone from nearly 9% in 2009 and are lingering around 4.5%, according to a 2020 multifamily market report by CBRE. Vacancy rates are similar in Utah and Weber counties, and even lower in Davis County, at about 3.5%.

What's the impact?

More Utah renters are struggling to make ends meet — or stretching themselves thin in order to make their rent payments.

Consider:

- Utah has an estimated 284,935 renters statewide. Of those, 115,875 — about 40% or 2 in 5 Utah renters — are considered "cost-burdened," or pay more than 30% of their income on rent. For about 52,890 Utahns — about 20% or 1 in 5 Utah renters — are considered "severely" cost-burdened, meaning they pay more than 50% of their income on rent, according to Utah's 2020 Affordable Housing Report.

- Statewide, about 65,815 Utah renter households are considered "extremely low income," or earn about 30% of the area median income. Of those, 72% are estimated to be severely cost -burdened, according to Utah's 2020 Affordable Housing Report.

- Most of these low-income Utahns are working. About 42% are in the labor force, while 21% are disabled, 21% are seniors, and 4% are going to school, according to Utah's 2020 Affordable Housing Report.

- A gap of affordable and available rental units for renters earning less than 50% of the area median income in Utah has widened over the past decade — from 41,052 in 2010 to 49,545 in 2018, according to the Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute's November 2020 report.

- Rental assistance and public housing waitlists are staggering. In Salt Lake City, alone, the waitlist for the most common assistance, Section 8 vouchers, is estimated at up to five years. Currently, there are more than 7,000 Salt Lake families on that list, according to the Housing Authority of Salt Lake City.

"It's heartbreaking," Britnee Dabb, deputy director of the Housing Authority of Salt Lake City, told the Deseret News about the 7,000-family, five-year Section 8 voucher waitlist. "I can't imagine being in that situation, where you're told, 'We would love to help you, but it could take up to five years' ... It's really hard for us to have to say that, but it's just the truth with how the funding is and the affordability and the availability."

Dabb said the waitlists are "definitely disheartening," but she urged Utahns struggling to pay their rents to still reach out to their local housing authorities for help, noting that the housing authorities work with landlords and other community partners to provide assistance.

"Let us help you," she said. "There is community support. If we aren't able to provide it, we are able to reach out (to other partners). Don't give up. Everybody deserves a safe place to sleep."

Dabb said the rental market — especially in Salt Lake City where high-rise apartment buildings are still being built, catering to top-dollar renters — is unfortunately not headed in a direction where renters might see some relief.

"It is absolutely crazy," she said.

Market forces — growth, demand and low vacancies — have led to the "longest apartment boom in our history," said James Wood, the Ivory-Boyer senior fellow at the University of Utah's Kem C. Gardner Policy Institute. And despite that boom, prices continue to go up because it's the simple product of demand outpacing supply.

"The boom continues," Wood said. "And so does the need."

Wood said he "wishes it were true" that assistance for renters was plentiful. "There is assistance out there, but the demand far exceeds it," he said.

He speaks from personal experience, saying he's been trying to get his granddaughter a housing voucher, but, again, Salt Lake County's waitlist was more than 7,000.

Rising prices will likely lead to more Utahns "doubling up," Wood said. More roommates, more families sharing living spaces, and fewer choices for renters.

"For the renter, it's just very much like those trying to get into home ownership," Wood said. It's a real barrier that takes time."

Holding her breath

Paula Barlow, 50, said she wanted to be there for her daughter, who during the pandemic lost her baby at birth as a stillborn.

"She's been having a really tough year," Barlow said.

So Barlow said her daughter wanted to move to Utah — but those plans changed when she struggled to even find an available rental, let alone one that she could afford. It was the same story for her when she looked to buy instead of rent. Everything was too pricey and selling way too fast.

"She had no luck here in Utah at all."

So, Barlow said she's supported her daughter from a distance — while having a tough year herself.

Barlow, who lives in a two-bedroom apartment in Murray, said she's been taking care of both her disabled mother and her husband, who she said has gone into kidney failure. She said he's also been in a wheelchair since he had a stroke five years ago.

"It's tough on me because I'm taking care of both of them, they're needing a lot of care, and I'm struggling with all of it," she said. "I'm trying to work and make money come in, but I'm not able to make enough."

Barlow said she pays about $1,000 a month for her apartment — a price she said she feels grateful for because it hasn't gone up in recent years. But she said she's holding her breath, waiting for a price increase, because she said rent prices have been going up for her friends.

But even without a rent price hike, Barlow said she's feeling the squeeze from the cost of other essentials creeping up.

"Wages aren't going up with the pricing of Utah, so it makes it kind of hard," she said. "Food's going up. Gas is going up. And it's hard for me to try to juggle it all with taking care of two disabled people, trying to keep down a job. Everything going on, sometimes it can be quite emotionally hard on me."

"I feel like it's a blessing from God," she said about not seeing a rent increase — at least not yet.

"I've been very blessed. ... But every month I wonder if it's going to happen with the way things are going right now."

How to get help

While housing authority waitlists are long and daunting, there is still help out there for Utah renters.

President Joe Biden's administration on Thursday extended the nationwide moratorium on evictions for renters who are unable to pay their rent during the pandemic from June 30 to July 31 — though federal officials warn it's expected to be the last time.

Fearing Utah could see a "wave" of evictions once the eviction moratorium expires, now scheduled for July 31, housing advocates recently urged renters to know there's still a significant chunk of government funding available for those impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic — to the tune of $180 million, according to Christina Oliver, director of Housing and Community Development for the Utah Department of Workforce Services.

"We really do want to encourage people who are on the fence about requesting assistance to just get online (at rentrelief.utah.gov) — it's a very quick application, it won't take much of your time — and see if it can help you," Oliver said.

To Paul Smith, executive director of the Utah Apartment Association, which represents landlords, more renters need to take advantage of the millions of dollars available to Utahns in rent relief due to COVID-19 — and he said more likely qualify for the assistance than they think.

"If I'm a low-income person in the state of Utah, there's no reason I shouldn't be paying my rent right now," Smith said. "Anyone making less than 80% (area median income) ... they should be getting their rent paid by the government."

With the COVID-19 rental assistance available, "low income renters have never had life better," Smith said.

"So what if prices are up?" Smith said. "What do you care if the government's paying your rent?"

Smith said he doesn't buy a "doom and gloom" outlook for renters.

"If they're struggling, maybe they don't know all of the programs out there for them," he said.

While there's tens of millions in assistance available for Utah renters impacted by COVID-19, the problem of a lack of affordable units — beyond the impact of the pandemic — still persists, housing advocates say.

The five-year, 7,000-family Section 8 waitlist is blaring evidence that needs far outpace assistance in a rental market that preceded and will likely persist beyond the pandemic, said Janice Kimball, CEO of Housing Connect, the housing authority for Salt Lake County, which uses the same waitlist.

"We're seeing just phenomenal (rent) increases when people do their annual renewal," Kimball said, noting that it's been common to see rates rise by $100 to $150.

The reality is, Kimball said, is "we don't have enough resources for the need."

"We tell (struggling renters) about tax credit properties, we tell them about public housing, Section 8 when it's open," Kimball said. "But there's a lot more need than we can even begin to address."

Tara Rollins, executive director of the Utah Housing Coalition, said the state of Utah's rental market — low vacancy rates, steadily rising prices and the state's overall growth — is pushing renters to their limits.

As the economy booms, Rollins said many renters are getting uprooted. With Utah's real estate prices soaring, apartment buildings are being purchased and renovated. Renters are facing price increases — or being told to move out when their lease is up.

"They were living in a place where they were getting by, and now they're going out into the market, and the market has changed so much," Rollins said. "So where does that person go?"

Meanwhile, landlords are facing no shortage of rental applications.

A 'dicey,' competitive market

When Sadie Texer, 21, and her friends started hunting for a Salt Lake City house to rent, she said they found about 40 or 50 candidates that could work within their budget. But when they started getting ready to submit applications, they realized it wasn't going to be easy.

House after house, they realized there were dozens of other renters eyeing the same property. They quickly learned that if they weren't among the first to submit an application, they didn't stand a chance.

"It was just so competitive," Texer said.

The whole process felt "dicey," she said. Even though Texer and her friends started looking in March — four months before her South Jordan lease would be up in June — months went by without any luck. It wasn't until they were down to a matter of weeks did they finally hear back that their application had been accepted for a four-bedroom house in Sugar House.

"The name of the game was last minute," Texer said. "It was really hard to find."

Texer said she's been living in a one-bedroom apartment in South Jordan for about $1,200 a month. She said she enjoyed living alone, even though it was expensive for a young professional who moved to Utah from Indiana to work for a Provo marketing company. She said the cost was worth it to her for that year, but she decided to move in with roommates to save money but also try living with her friends.

The four-bedroom Sugar House house rental will cost Texer and her two other roommates about $900 each a month, totaling about $2,700 a month. She said the price seemed "reasonable" to her, considering the desirable area of Sugar House.

"Honestly, it was just what we could get," she said.

Paying the price

Her love of mountain sports — mountain biking and snowboarding — was a big reason Kayla Smartz, 31, moved to Utah from Michigan two years ago.

But over the past year, she hasn't been able to enjoy the mountains like she'd hoped, even though she's paying a steep premium to be able to live near the Wasatch canyons.

She suffered a torn ACL when she took a tumble while skiing a steep run at Deer Valley in January. The surgeries to repair her ACL didn't go smoothly. Complications — a bacterial infection from the first surgery — led to a second surgery to attempt to clear infection. When that didn't work, Smartz endured a third surgery to remove the ligament, leaving her without an ACL. Now she's hoping the fourth surgery will go better, and she'll soon be able regain her strength to mountain bike, ski and snowboard again.

Even though she laments her injury sucked a year away from her passions, she's kept high spirits, eager to get back on her bike and snowboard. But in a year of stress over her own health and medical bills, Smartz has also had to navigate a whole new stress: paying her rent.

Smartz, drawn to the Wasatch Front's mountain range, lives in a one-bedroom apartment with a price tag of $1,250 a month in the Foothills area of Salt Lake City.

"It's really expensive," Smartz said. But she says it's worth it for the location, near the canyons.

But Smartz — who works in admissions for the University of Utah — estimates about half of her paycheck goes straight to housing costs, including utilities. She said she's only been able to make that work within her budget because she doesn't have a car loan, and student loan payments have been on hold amid COVID-19.

"Honestly, those are the only reasons I'm able to afford this," she said.

When Smartz first moved into the apartment, she was much more financially stable. That was before her ski accident. It was also before the pandemic hit. She was working as an operations manager for a local company and her salary was much higher, but then she got laid off. Then, when COVID-19 came to Utah, she lost her second job working at concerts.

"So things really changed," she said, adding that she was facing a decision of whether to renew her lease or not. The thought of moving was daunting, too, so she decided to sign again.

"That was absolutely terrifying," she said. Since then, Smartz said she's ending up "making it work."

Then she lost her ACL. Smartz said she's beyond grateful that she has health insurance, as well as a savings cushion and support from her community through a GoFundMe to help her with medical costs. But she said she knows how precarious her situation could have been — and how, for many, a medical emergency could mean the difference between paying rent or losing housing.

"I'm extremely grateful," she said. "Extremely grateful that it didn't impact more than it did."

But Smartz acknowledges the downsides of paying steep rent. Back home in Michigan, she said she has friends who have already purchased homes. The $1,250 monthly rent bill has prevented her from saving up to buy a house — though she said the prices Utahns have been paying in today's housing market are "mind-blowing."

"So I kind of feel stuck here," she said, though she added, "I love it."

"I'm going to deal with (buying a house) later and put it on the back burner," she said, "But I'm probably going to regret that down the road."