Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SPRINGDALE, Washington County — The level of cyanobacteria for the north fork of the Virgin River fell enough earlier this month that Zion National Park officials downgraded a danger advisory to a warning advisory. But they say visitors should still use caution when in the water this summer.

The danger advisory for the North Fork Virgin River was first issued in late March. On June 2, park officials downgraded it to a warning advisory based on monitoring results gathered in May.

The warning advisory means visitors can skim the water, including popular hiking spots like The Narrows, but are still advised to avoid any swimming or submerging their heads in the river. That's because biologists say there still is a risk for potential long-term illness in addition to short-term effects from exposure, such as skin and eye irritation, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

The downgrade came after cyanobacteria levels in the river fell from over 90 micrograms per liter to levels between 15 and 90 micrograms per liter.

"At this time we're advising recreators to avoid primary contact recreation. That's not avoiding water altogether; that's just avoiding swimming and submerging your head. Hiking through the water column, as long as you're not engaging in primary contact recreation, should be relatively low risk," said Robyn Henderek, Zion National Park's physical scientist.

Kate Fickas, an aquatic biologist and environmental scientist for the Utah Department of Environmental Quality, added that a health watch for areas of the river in locations outside of the park remains in place and will likely continue for some time. She said the state just doesn't have enough resources to adequately measure levels of cyanobacteria in those areas, but it's assumed that it exists in the water outside of the park.

"So we ask recreators to do exactly (what's recommended for Zion National Park)," she said, pointing out there is still no threat to the drinking water or irrigation waters in the region.

Biologists with the park and the Utah Department of Environmental Quality provided a Virgin River algal bloom update Wednesday, which was meant to better explain the unique algal bloom found in the river and highlight what it looks like so people can spot it and avoid it. Despite the recent downgrade, biologists also warn that if conditions don't improve, the algal bloom may become worse as the summer continues.

Zion National Park and the Utah Division of Water Quality first learned of an algal bloom issue last summer after a pet died from toxic algae consumption. Fickas said scientists were originally puzzled when they were contacted about the possibility of an algal bloom in the Virgin River because Utah blooms are typically found in lakes or reservoirs.

But researchers also knew that places in California and New Zealand started dealing with something new called benthic cyanobacteria, which is algal blooms that sit at the bottom or the sides of a river. When state biologists visited the park to take samples, that's exactly what they found.

"We found some really interesting species within the park. It's a new phenomenon — Utah is really only the second state in the country to be ahead with these types of cyanobacteria blooms that are distinctly different from blooms within lakes and reservoirs," Fickas said.

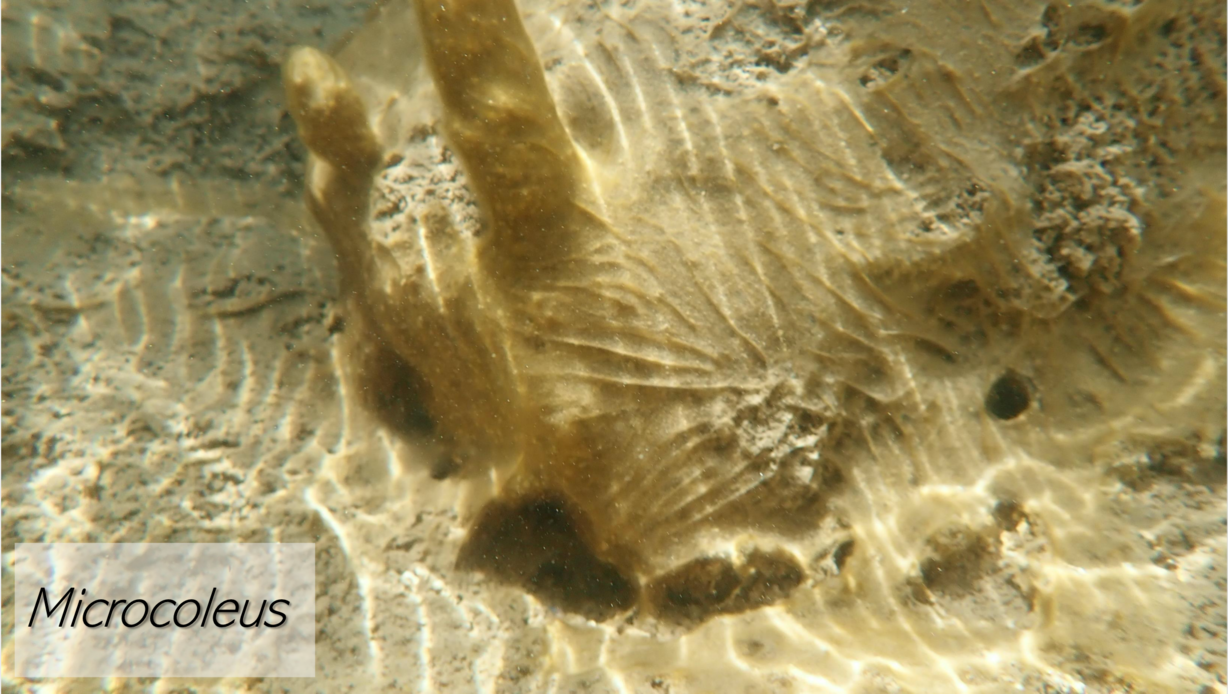

Henderek said the benthic cyanobacteria in the Virgin River is growing along the bottom of the river and its water column, as well as along the edges of plants. They found microcoleus, which she called a "potent" neurotoxin, that starts out dark green in appearance before turning light to dark brown.

"It's growing in abundance, so it's a real risk to recreators who may be recreating in an area like this," she said.

Biologists also found a genus called nostoc, which Henderek described as dark brown "gelatinous pearls" in La Verkin Creek, as well as tychonema in North Creek.

It's still not exactly clear what caused the benthic cyanobacteria to appear in the Virgin River, but researchers do know the risks it can cause. For example, researchers found that the cyanobacteria found in the river easily floated to the surface when stepped on or touched, which means it's pretty easy for anyone to accidentally ingest them. That, Henderek said, is the biggest risk with the cyanobacteria found in the river.

"Inside these bacterial mats is where the toxins are; and so, incidentally ingesting these pieces is a real risk to recreators," she said, adding that a reasonable "worst-case exposure scenario" could involve a young child playing on the edge of the river accidentally disturbing the bacterial mats and ingesting the pieces of those mats.

The algal bloom arose just as Zion National Park's popularity rose even more than already before. The park ended 2020 with the busiest fall visitation on record and, with over 1.8 million visitors already estimated through May 2021, is still on pace to shatter the park's visitation record. On top of that, the summer months are historically when it receives its highest visitation.

For those planning on a trip to Zion this summer, Henderek said the most important thing is to check whatever the current advisory is for the Virgin River and applying the recommendations to "recreate responsibly" before jumping in the water. Fickas added those looking to jump in the river outside of the park should follow similar procedures just because there is an assumed cyanobacteria risk.

The Utah Division of Water Resources set up a website dedicated to the latest information about where algal blooms are in Utah.

Meanwhile, researchers said it's still unknown how long the algal bloom will remain an issue for the Virgin River, especially since it's a situation researchers are just learning about. Like lakes, benthic cyanobacteria seem to thrive in warmer weather, so southern Utah's traditional summer monsoon pattern may be the only way to fix the problem — if it returns this summer.

"The only thing we really know to essentially treat benthic cyanobacteria that we find in rivers is large scouring events that occur after rainfall," Fickas said. "We're in a very severe drought, Zion National Park received almost no rain last year, not enough to scour.

"With the drought forecast looking worse and worse for the state, combined with the lack of precipitation events in general," she added, "we're potentially looking at an advisory of both sides of the park boundaries all summer long — and similarly across our lakes in the state."