Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

KANAB, Kane County — A small group of tyrannosaurs were roaming the earth together in what is now southern Utah about 76 million years ago when a flood, likely seasonal in nature, sent them to their graves.

There, they rested for millions of years as the entire environment of the region changed: rivers and lakes dried up, fires scorched the land, and new species emerged on the planet.

That's the final theory from a "once in a lifetime" mass tyrannosaur death site paleontologists stumbled across at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument less than a decade ago. Their findings, published in the journal PeerJ Monday, argue that the mass death site isn't just the discovery of a handful of dinosaur bones; rather, it provides proof the fierce dinosaur species lived in packs when they roamed the earth, which could be the final evidence needed to prove a "controversial" theory that's emerged in the paleontological world over the past two decades.

The study provides the latest evidence that seems to conclude that tyrannosaurs were actually social carnivores, like wolves, and less like solitary predators as they had been believed and depicted. It's also the most recent and not believed to be the last scientific work to come from a massive dinosaur fossil site at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Stumbling across a gold mine

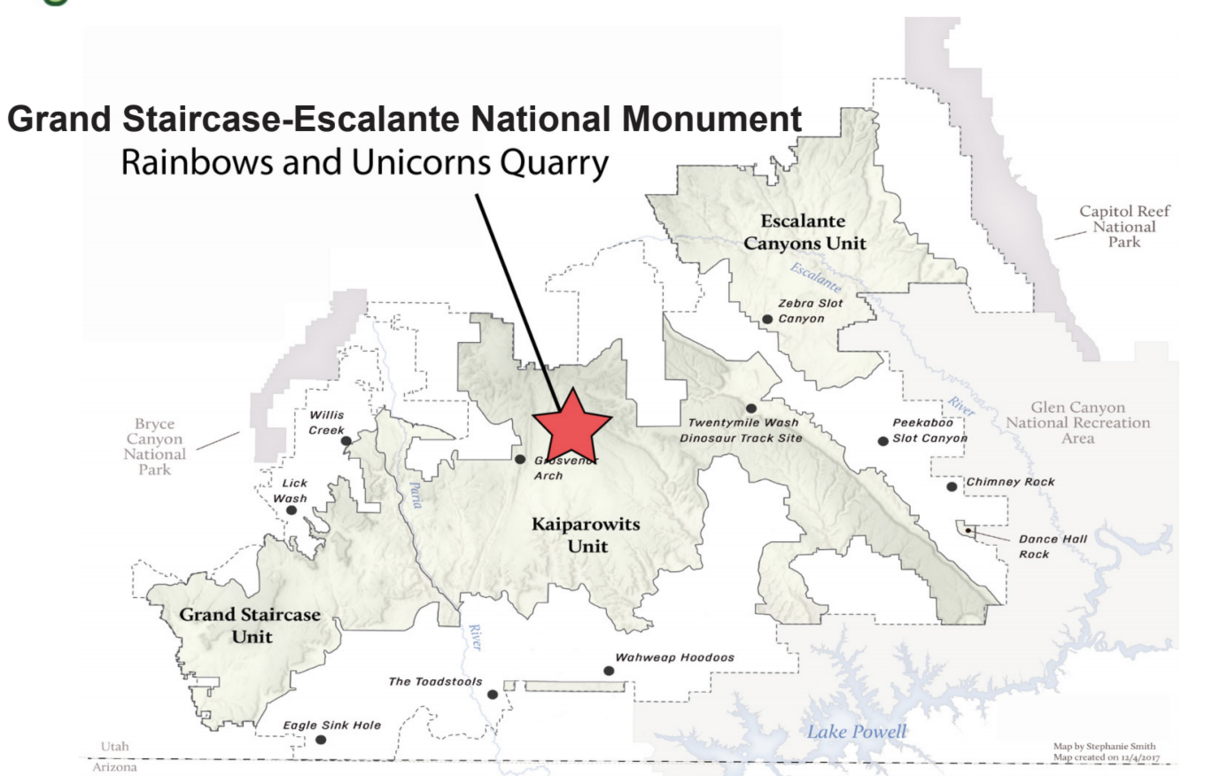

The large-scale study began in 2014. That's when Dr. Alan Titus, a paleontologist with the Bureau of Land Management, first discovered what is now known as the Rainbows and Unicorns Quarry site at the national monument. The site has since produced the largest mass death site for tyrannosaurs in the southern United States.

In addition to the tyrannosaurs, the site is where paleontologists have uncovered several fish and ray species, seven different species of turtles and two other dinosaur species, as well a prehistoric alligator — although it's not believed that all of the species uncovered died at the same time as the tyrannosaurs.

"I consider this to be a once-in-a-lifetime discovery for myself," Titus said. "I probably won't find another site this exciting and scientifically significant in my career."

The site in the Kaiparowits Plateau area of the Grand Staircase-Escalante area got its unique name sort of as a playful jab at Titus, who is known within some in paleontological circles as more of a bullish and buoyant researcher. When he first described the site, a former employee of his joked that Titus always made every discovery sound as unbelievable as "rainbows and unicorns."

But others agreed that the site provided a prehistoric treasure trove worthy of that level of excitement.

"(A field worker for me said) this site really is 'rainbows and unicorns,' and so the name just stuck," Titus recalled.

Four or five tyrannosaurs, officially identified as teratophoneus, were among the findings. It was estimated that the dinosaurs ranged from 4 to 22 years old at the time they died. Their fossils stood out to researchers not just because they were together, but they were the only non-aquatic species among the fossils.

After the dinosaur fossils were dug up, a team of researchers conducted all sorts of tests and analyses on the bones uncovered and the rocks around them. This led them onto a path to possibly providing definitive proof about the social behavior of the extinct species.

What happened to the 'unicorn' dinosaurs?

Titus explained that the fossils of the tyrannosaurs were originally believed to have been "exhumed and reburied" through the action of a river through the area.

As they continued to study the fossils, the team of researchers now believe the fossils found at the site are proof that a pod of tyrannosaurs were together when they got swept away and killed during seasonal flooding. Their carcasses ended up in a lake where they were left mostly undisturbed until the river cut through the bone bed, Titus said.

If that were true, the site is proof that tyrannosaurs were social species. But to prove the Utah findings to fellow researchers, Titus knew he needed scientific evidence that undeniably showed that all of the dinosaurs were at the same place at the same point of time when the flood happened.

That's when he called up Dr. Celina Suarez, an associate professor of paleontology at the University of Arkansas, and Dr. Daigo Yamamura, who was also at the university at the time. They used a "multi-disciplinary approach" of physical and chemical science through carbon and oxygen analysis within the dinosaur bones and rock, which revealed that the bones weren't the result of different time periods or locations that happened to end up at the same site.

In short, the dinosaurs died at the same time at the same place and were fossilized together. Organic matter collected from the site seemed to indicate that the bones were winnowed and then reburied in a river sandbar. After the waters dried up, there was also a low-temperature fire that consumed redwood on the land between the time the dinosaurs died — 76.4 million years ago — and now.

"The similarity of rare earth element patterns is highly suggestive that these organisms died and were fossilized together," Suarez said in a statement Monday.

The researchers said the fact that all of the dinosaurs were together when they died provided "more compelling evidence" that tyrannosaurs were social creatures that habitually lived in groups and didn't roam alone.

In all, researchers from the BLM, University of Arkansas, Miles Community College, Colby College, James Cook University (Australia) and Denver Museum of Nature & Science collaborated on the study.

A shift in the tyrannosaur paradigm (and more work to come)

With researchers coming to the same conclusion at different sites in recent decades, one may think that the theory that tyrannosaurs were more social creatures may become more accepted within the paleontological world.

Dr. Philip Currie first formed the theory more than two decades ago after the first mass tyrannosaur death site was discovered in Canada. Some in the science community debated the idea and viewed the site as circumstantial or some sort of one-time finding.

During a presentation of the study's findings Monday, Titus pointed out that it's not extremely debated within the scientific community that some dinosaurs were "gregarious" and banded together in herds. That's especially true of various herbivore dinosaur species.

"It's a little bit more controversial when you start talking about gregarious predators because predators don't instinctively or automatically become gregarious, at least as readily as plant-eaters," he said. "When you think about predators, there really aren't lots of examples today of large predators that behave in complex social groups like wolves or lions. ... Most predators are solitary."

Many predators are solitary because they are competing against each other for food. A group of dinosaurs banding together to carry out hunts with possible leaders would indicate the species were smarter than originally believed, and that's why many dismissed Currie's theory.

"The idea large predators like t-rex could have actually been social, complex hunters with role-playing and division of the hunt — with ambushers and chasers and then sharing in the kills and all that — is somewhat controversial," Titus added. "A lot of researchers feel like these animals simply didn't have the brainpower to engage in such complex behavior."

Another mass death site in Montana led to more suspicion about the new theory regarding how tyrannosaurs lived; yet, it still wasn't really enough to persuade skeptics. The site at Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument is now the third of its kind.

For Titus, that's enough proof to show the species lived in packs. All three, in his opinion, were caused by "improbable events" that led to the creatures dying together. He said that's why there are three mass death sites in completely different areas of North America and no known mass death sites for other predator species like the allosaurus.

"It's very unusual to find this, and yet it keeps repeating itself with tyrannosaurs," he said, arguing that most be an indication of "some behavior" that was different in tyrannosaurs.

This site, the spectacular accumulation of tyrannosaurs but also the other assembled pieces of evidence that came from work from Dr. Suarez and others, really puts that tipping point — really pushes us to the point where we can actually show some evidence for behavior.

–Dr. Joseph Sertich, curator of dinosaurs at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science

The biggest reason there have been differing opinions on the matter is that most fossil records won't preserve evidence of behavior, such as hunting in packs, said Dr. Joseph Sertich, curator of dinosaurs at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science. He said there needs to be "amazing evidence" presented to change minds.

That's why he believes the study published Monday has the potential to do that.

"This site, the spectacular accumulation of tyrannosaurs but also the other assembled pieces of evidence that came from work from Dr. Suarez and others, really puts that tipping point — really pushes us to the point where we can actually show some evidence for behavior," he said.

Another reason that the researchers are confident in their findings is that there is at least one descendant of the dinosaurs that acts in the pattern theorized by Currie and backed by the study published Monday: the Harris's hawk. Titus described the species as a cousin of the tyrannosaur.

"They form groups of multiple individuals; they have communal raising of the young; they share in kills, and they actually have a division of labor when they hunt," he said, referring to different roles the birds play when they prey on other species.

For the group of researchers, it goes to show that it's a characteristic that was possible in dinosaurs because it exists in some birds many millions of years later.

Meanwhile, the findings released Monday weren't the first nor will they be the last prehistoric research to come out of the quarry site. BLM officials said this area has become one of "world-class" paleontological study. Secretary of Interior Debra Haaland didn't visit the site during her recent review of Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, as it wasn't land moved out of protection by the shrinkage of the national monument in 2017, but she did visit the field office where research remains ongoing.

Researchers said there are more plans to research the site in relation to the study published Monday. The group said they hope to find even more evidence from the site to over a "greater degree of certainty" regarding the truth of how tyrannosaurs lived millions of years ago.