Estimated read time: 8-9 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's note: This article is a part of a series reviewing Utah and U.S. history for KSL.com's Historic section.

SANDY — Richard Spedden views himself as a generalist who finds himself wrapped up in all kinds of subjects he's curious about.

Geology and the canyons of southeast Salt Lake Valley could be considered two of those interests. As Spedden would venture into Little Cottonwood Canyon for ski trips, something about the terrain nagged him. He felt something about it just didn't add up to the science he read about it.

In March, as COVID-19 lockdowns forced people to stay inside, the Sandy resident found himself with more time to focus on it and quickly got to work investigating what became a half-year passion project.

Despite no formal education in geology — his educational background was computer science, mechanical engineering, and business — he slowly pieced together a theory that challenges a 130-year-old belief about how the area formed and the area's topography.

Spedden's research suggests that terrain in the southeastern Salt Lake Valley was formed more by a tsunami triggered by an earthquake rather than an earthquake itself. It's a new theory that could also rewrite the history of a prehistoric Lake Bonneville flood and give a better understanding of how the land in the Salt Lake Valley moves.

Spedden is slated to present his findings Friday at the Geological Society of America 2020 Annual Meeting — a conference featuring some of the top geological researchers across the globe that's been held yearly since 1888. In his words, the research is an answer to a "geological murder mystery."

Creating a paradigm shift

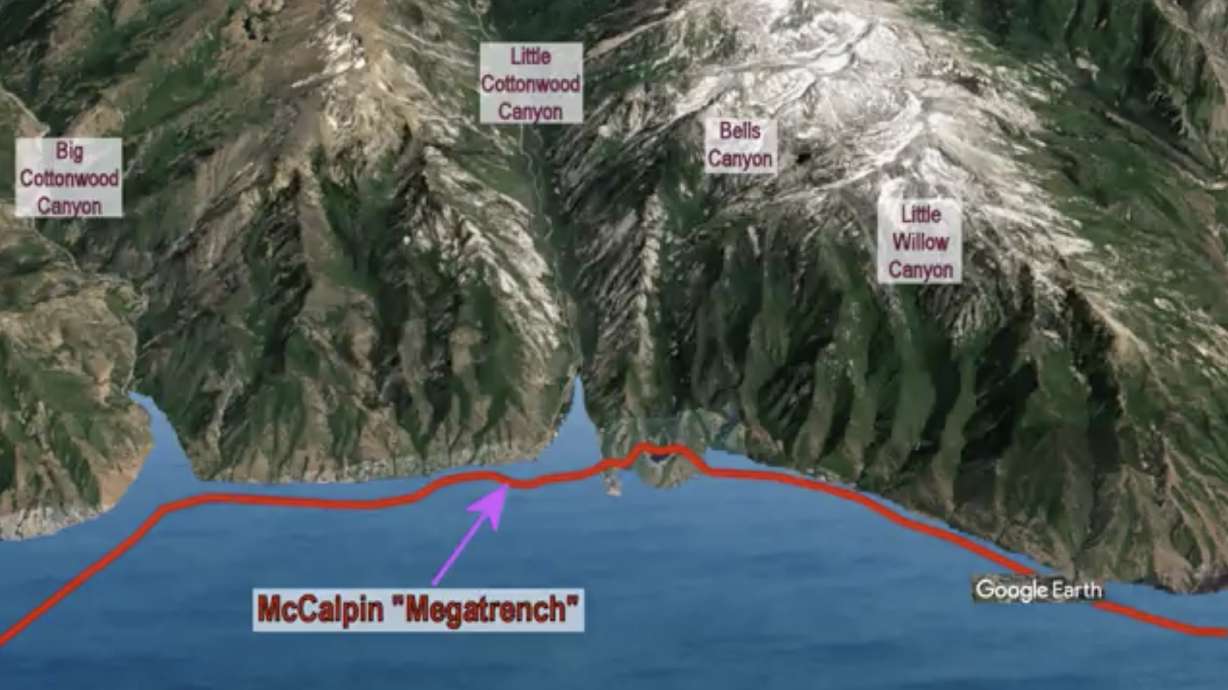

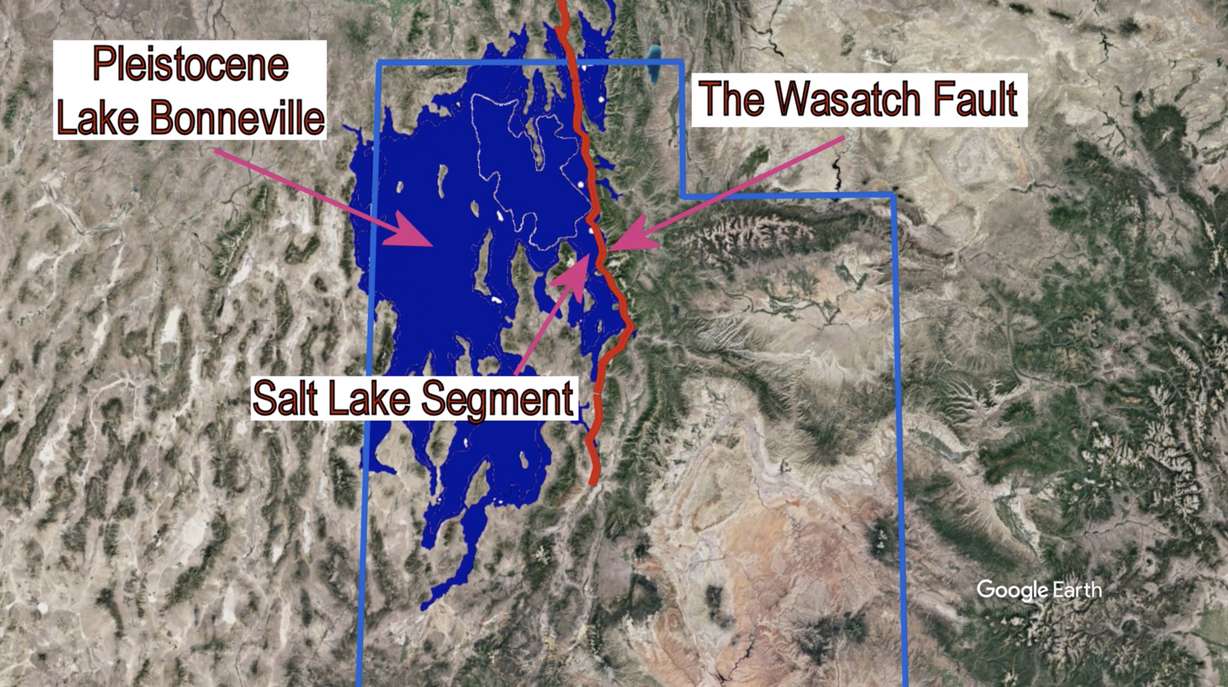

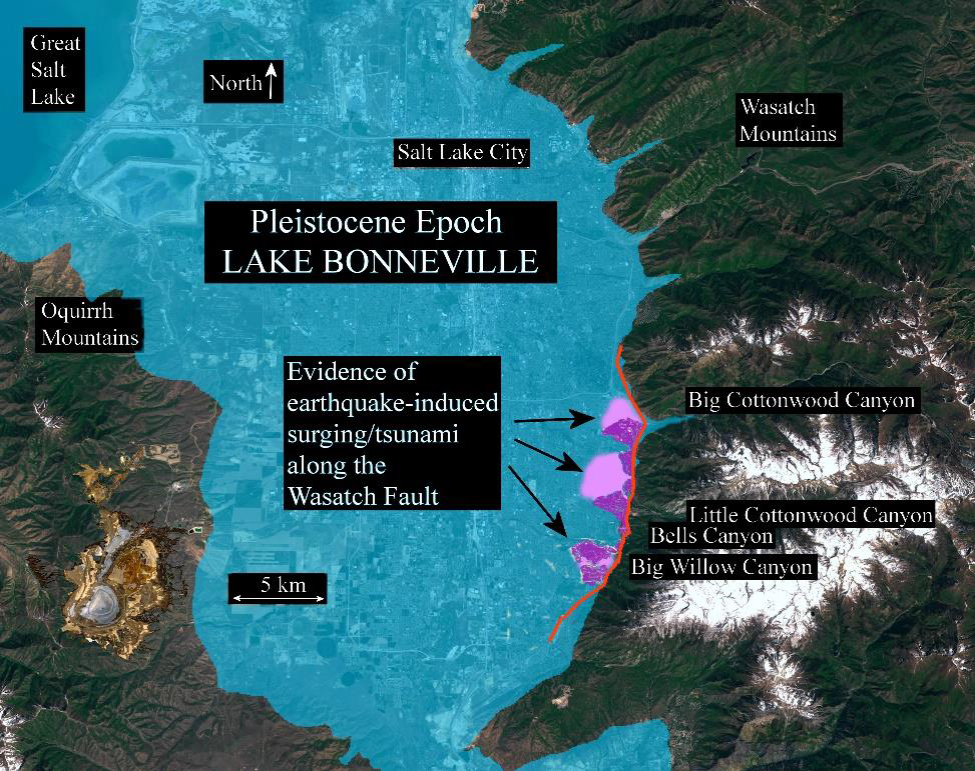

The research focuses on the southeastern section of the Salt Lake Valley between Big Cottonwood Canyon and Little Willow Canyon. It covers the space at the edge of the cities of Cottonwood Heights, Sandy and Draper, and the Wasatch Mountains. This area was once under water as it was a part of the eastern edge of the large prehistoric Lake Bonneville, which covered most of what is now northern Utah.

The section is also by the Wasatch Fault, which is a large fault line underneath the ground from central Utah north through Idaho. It's an area that's been studied several times over the course of a century.

The first theories of how the area formed started in 1890 when prominent geologist G.K. Gilbert identified the land as an example of a topographic feature known as "graben." Under Gilbert's theory, the high water table of Lake Bonneville was subject to liquefaction during an earthquake, which caused a depression along an earthquake fault line which drops down as a block. The feature is most distinguished at the mouth of Little Cottonwood Canyon.

Gilbert's scientific work in the area is largely known, and there's a park in Sandy named after him today. The entire area is a standard field trip for students, geologists and aficionados alike to study unique topography, Spedden said. A few subsequent trench studies conducted since 1890 have pointed to a big earthquake in the area creating graben and other scarps sometime between 14,000 and 18,000 years ago during what's known as the Pleistocene era.

The massive Lake Bonneville flood is believed to have occurred between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago. Researchers estimated that water flowed at 15 million cubic feet per second when it happened.

What Spedden argues from previous studies is that not all of the geological features of the southeast Salt Lake County area align with the original theory of graben. In an interview with KSL.com, he explained that he believes a major earthquake happened — likely within the time frame offered in previous studies — and then "physics kicked in."

"If you have a major earthquake happen underneath a lake, something's got to give," he explained. "If the Wasatch Fault drops; that suddenly drops a whole arm of Lake Bonneville down below where it should be."

He pointed toward factors of what would happen to a large lake as the earth shook underneath it. It starts like a bowl of soup in your hand. If you move one side of the bowl slightly down, the volume of the bowl surges past the uneven area before shooting back and forth and coming to a rest.

The shockwaves of what would be a tsunami also played into this. Spedden likened the shockwave to water hammer in pipes.

"My belief is that what happened here is that there was surging in the valley and that's what all the evidence is pointing toward," he said. "Think of a wave at the beach. Think about the amount of force on you when that wave starts to go back out. It's being dragged out to sea.

"That's what happened to all these stable till landmasses in the 10 square miles of glacial till landmasses here," he continued. "They were on a very, very weak (sand) layer underneath. When that surging layer came up, it just dragged it out to sea to a certain degree."

This event created distinctive distortions in geological features near Little Cottonwood and Bells Canyons, per his research.

As Spedden studied the area further, he was able to tie in the Bonneville flood — considering that it is believed to have occurred relatively close to the same timeframe as the earthquake. He argued in his research that the geographic evidence indicates Lake Bonneville was at a high point inside the area reviewed at the time of what was likely "an extraordinary" earthquake/tsunami event before it experienced a significant drop in water level.

That would mean the graben was actually a fissure, and other land features in the area were a result of the sudden water level decline. Land features in northern Utah and southern Idaho indicate possible impact from "concentrated" energy.

"The inescapable conclusion is that immediately following the (prehistoric earthquake), the lake levels started the rapid drop of the Bonneville flood," Spedden concludes during a 12-minute video presentation of his findings for the GSA meeting.

He added that it's likely the seismic incident may have "killed" Lake Bonneville and the area of southeast Salt Lake County, which he dubbed the Gilbert Trough, was the "smoking gun."

An unlikely path to research

What might make the research more fascinating is how it came together. In fact, Spedden might be the person most surprised that he's presenting his findings at the GSA Annual Meeting this week. It's not that he's shocked scientists were willing to listen and review his findings, it's because geology isn't his day job or main expertise.

The study became an outlet for a burning desire to understand how the terrain formed. He didn't expect his research to tie into Lake Bonneville in any way when he first started.

"It was not my intent to disrupt anything," he admitted. "I really wasn't looking to come up with something new. All I was trying to do was understand the Little Cottonwood southern lateral moraine because when I looked at it, it didn't fit the explanation that was out there about why it was the way it was."

He reached out to local geologists with his theory early on but the idea was dismissed. One geologist suggested that Spedden put together a peer-reviewed paper, so that's exactly what he decided to do. For him, the "ethical obligation" to inform the scientific community of what he believed he discovered outweighed what he said was difficult work.

He's heard a mixed bag of feedback since finalizing the paper. A representative from the U.S. Geological Survey gave it a glowing review; another reviewer disputed some of the findings based on previous research. A spokesperson for the Utah Geological Survey told KSL.com that a geologist currently conducting work at Big Cottonwood Canyon reviewed the work and responded with "geologic inconsistencies and problems with his idea."

Spedden shrugged off the negative critiques. To him, his presentation Friday will mark the end of his goal to showcase what he discovered.

"I've enjoyed the work of others in this field for many years and if I could advance the ball, that would be great," he said.

Future studies

If Spedden is right about his research, he's optimistic that it will lead to future discoveries about the land all over the Intermountain West that was once submerged under Lake Bonneville and determine what exactly happened to it thousands of years ago.

It's not just something that would change history, but it has current implications. For example, he suggested that it might mean a need to reevaluate Wasatch Fault slippage rates for future land movement. It's also something that may have implications for the land where reservoirs and dams are in the region.

As for his future, Spedden doesn't foresee conducting another geological study himself — that is unless he finds himself down another rabbit hole. He joked that he's completed his contribution to the field whether geologists want to accept it or not.

Utah Geological Survey officials say they encourage anyone like Spedden to "observe, question and investigate" Utah's geological surroundings.

While the Sandy residents awaits more feedback on his work following his presentation this week, he's hopeful that residents will find similar interest in the unique terrain.

"I firmly believe we all just need to go through our lives learning as much about everything around us as we can. It just makes life more interesting," he said. "I mean everybody looks at their backyard and such and they think it was always this way; but every time I look at the Salt Lake Valley, I envision the valley filled with this massive lake with glaciers cascading down into the lake.

"It must have been really spectacular and that's a fun thing to think about."