Estimated read time: 5-6 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Utah’s population has increased more than 45 percent over the last four decades. The state’s prison population, however, has risen nearly 565 percent in that same time, according to a recent study.

A new report released by the American Civil Liberties Union in Utah says 6,476 state residents were imprisoned as of May, and the number is set to reach 7,200 by 2031.

In a nationwide effort to reduce incarceration rates in a country well-known for its overcrowded jails, the ACLU released similar studies in each state with proposed changes they say could drastically reduce incarceration rates.

If Utah implements these changes, the state could nearly cut its incarceration rate in half and save $250 million, the study says. These proposed changes would include:

- Expanding Medicaid funding for all Utahns so those suffering from mental health issues or substance addiction could receive the treatment they need and use the programs as alternatives to incarceration.

- Reducing time or offering alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent crimes.

- Reducing penalties or eliminating incarceration for property and public order crimes.

- More transparency and accountability in parole board decisions.

- Eliminating incarceration for technical violations of parole or probation.

- Reducing time served and instituting alternatives to incarceration for those who distribute drugs as well as ending all incarceration for drug possession.

- Supporting decriminalization and alternatives to incarceration.

- Creating mechanisms to review and assess decisions made by prosecutors.

Priorities

If Utah had to pick just one change that would make the most significant impact, however, the ACLU’s smart justice coordinator Jason Groth believes instituting programs for those transitioning from prison back into society would make the biggest difference in the lives of the state’s incarcerated.

“If we can get ways to provide structure for those people that are coming back into the community, if we look at housing, if we look at employment and transportation — those can provide people the stability so they don’t run into a lot of the issues that they otherwise face without those support structures,” Groth said.

Parole and probation violations made up about 76 percent of all prison admissions in 2017, Groth said. Providing support to those re-entering society could drastically reduce that number, he added.

Allowing prisoners to leave on parole and probation was meant to alleviate the surge of people entering the state’s correctional facilities, said Salt Lake County District Attorney Sim Gill. Yet technical parole and probation violations are the single biggest contributor to that prison influx.

Technical violations usually include misbehavior on the part of the parolee that wouldn’t normally result in arrest. But while on probation or parole, that violation will land the offender back in jail.

“It's been counterproductive because we're actually now using that opportunity which was supposed to give us relief as a rationalization to actually drive up that population,” Gill said.

Gill also believes bail reform and decriminalization of some nonviolent crimes could slow that high influx of incarceration — even across the nation. But Utah could also benefit from some specific changes that pertain to unique problems in the Beehive State, Groth and Gill agree.

What does Utah need?

Nearly half of those screened in Utah jails were identified as needing an additional assessment for substance use disorders, and 40 percent required additional mental health assessments, the ACLU’s study found.

“Full Medicaid expansion would give us that opportunity … to impact a large number of people who are cycling through the criminal justice system without any meaningful access to treatment,” Gill said.

Utah also suffers from a racially disproportionate incarcerated population, Gill and Groth said. Though states across the country face this issue, it’s an especially prevalent problem in Utah — especially with indigenous populations, Groth added.

Though Native Americans make up 1 percent of the adult population in Utah, they made up 5 percent of the incarceration population in 2017, according to the ACLU’s study. Black adults were incarcerated at a rate 8.3 times higher than that of white adults, and Latinos comprised only 12 percent of the state’s adult population but made up 19 percent of its 2017 prison population.

The University of Utah College of Law found that Native Americans in Utah were four times more likely to receive disciplinary action than white students. Many believe reducing the race disproportionality in Utah prisons begins with what the ACLU calls the “school-to-prison pipeline” — a disproportionate tendency of children and young adults from disadvantaged backgrounds to become incarcerated because of harsh local and school disciplinary action.

Will the changes work?

While Gill agrees with 90 percent of what the ACLU’s study suggests (and says he’s advocated for much the same thing for the last 18 years), he’s not sure the proposed changes could truly reduce the incarceration population by half.

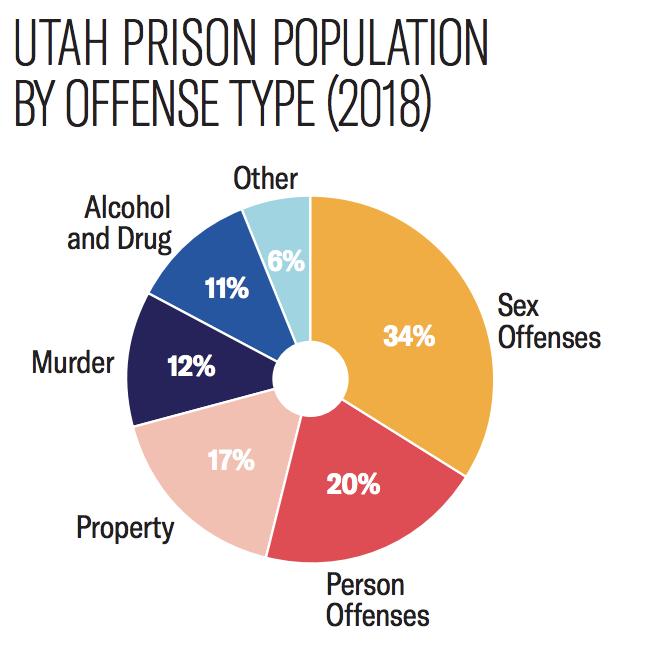

According to the study, 34 percent of those incarcerated are there on sex offenses, 20 percent are person-on-person offenses, and 12 percent are murder.

“That roughly gives me about 66 percent of the people who are there who probably need to be there,” Gill said.

Eleven percent of the population are there on alcohol and drug-related charges and, though Gill said he’d need to break down the data a little further, law enforcement “doesn’t send people to prison because they're public intoxicants,” he said. Alcohol offenses are usually tied to felony DUIs, meaning it's the person’s third DUI offense, he explained.

But though Gill’s not sure the impact of the changes would quite be at the level claimed by the ACLU, he’s “very optimistic that this is doable.”

“Studies like this are not something we should fear, but something we should embrace because they give us opportunities to make informed decisions,” he said.