Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — It's Judi Yaworsky's favorite time of the year.

From the end of August to the end of October, two days a week, Yaworsky and the four other school nurses who care for Salt Lake City School District’s 23,000 students will screen them for their vision.

They will screen roughly 1,200 students per week while simultaneously writing health plans, completing paperwork and handling daily medical emergencies at the seven to nine schools they each are in charge of.

"We're stretched thin," Yaworsky said. "But we'll do whatever we have to do. That's what school nurses do. And honestly, you just work until you get it done."

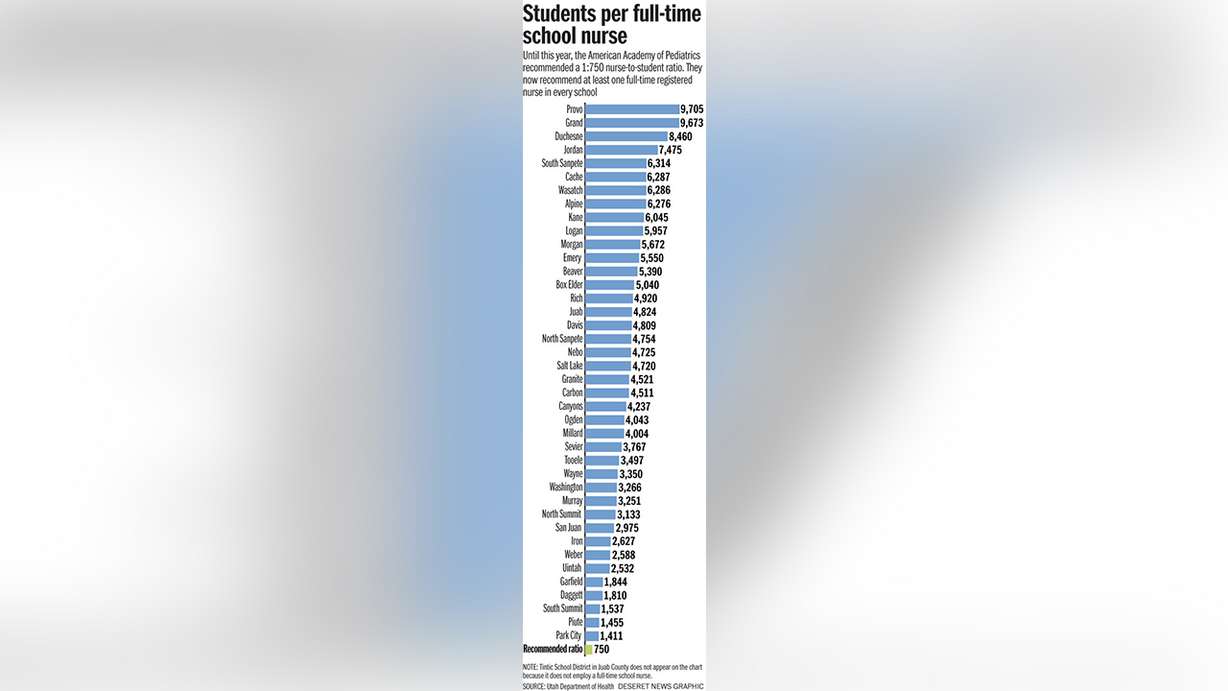

Each Utah school nurse, on average, serves more than 4,300 students, according to a recent report from the Utah Department of Health — among the worst student-to-nurse ratios in the nation.

"I've been in school nursing for 16 years, and as long as I've been in school nursing, Utah's always been ranked near the bottom," said BettySue Hinkson, the state health department’s school nurse consultant.

Hinkson said school nurses have worked hard to make it work. But with the student population swelling and the percentage of students with chronic illnesses growing each year, nurses are growing increasingly overwhelmed, she said.

None of the school districts in Utah meet the American Academy of Pediatrics' recommendation that school districts have one full-time nurse for each school, according to Hinkson.

Park City School District is close — with six nurses for seven schools.

One school district in the state — rural Tintinc School District — has no full-time school nurse at all.

Hinkson said most school nurses in Utah cover between five and 15 schools.

The setup leaves many nurses shuttling from school to school, training staff members to respond to medical emergencies and leaving precious little time to visit with students in the traditional clinic setting.

"When we meet with other nurses from around the country, we just kind of shake our heads," Hinkson said. "It's like we have two different jobs."

Many school nurses in Utah deputize teachers, secretaries and other volunteers to help children with medical conditions. That can include anything from handing out ADHD medication to helping children with diabetes administer insulin at lunch.

That’s a cause of concern for parents and nurses alike.

“It makes us a little nervous,” said Ellie Bodily, president of the Utah School Nurse Association. “(School districts are) feeling like a registered nurse doesn’t need to be present, that a medical assistant or some help aide can do the job of a nurse. Of course, they can hand out Band-Aids and ice packs, but it’s the process of assessment that’s missing when you hire somebody like that.”

It has also led to some close calls.

Michelle Fogg’s daughter Emalee was in second grade when her throat began to feel funny after taking a bite of pizza.

Fogg, a Salt Lake City resident, said school staff didn’t recognize that Emalee, who has severe food allergies, was going into anaphylactic shock.

By the time the school called Fogg and she made it to the building, she saw that Emalee was drooling into her lap because she was unable to swallow her spit.

“I said to the secretary, ‘She’s having an allergic reaction and I need to give her an EpiPen. Call 911,'" Fogg said.

Fogg, the founder of the Utah Food Allergy Network, said she has advocated for more school nurses for years.

“Those staff members had been trained," she said. "They knew she had food allergies. And they did not pick it up at all.”

* * *

Not having a school nurse in the building can be particularly hard on children who have illnesses like Type 1 diabetes that need constant monitoring.

Brittani Uribe, an Ogden resident, said school staff called an ambulance for her 6-year-old daughter last year after her blood sugar dropped to seizure levels.

“She had fallen out of her chair. … Her eyes were rolling into the back of her head,” Uribe said.

Uribe got there before the ambulance and started helping the aide give her daughter sugar. But she was upset that a school nurse wasn't available.

"They are great people," Uribe said of the aides. "I really appreciate their help and everything that they do."

But aides, she added, aren't medical professionals.

And when it comes to the daily trials of managing her daughter's insulin, Uribe said she has to leave work and go to her daughter’s school four or five times a month because no aides or nurses are available to help her daughter dose her insulin.

It’s become so constant that Uribe, a single mom, is studying to become a hairdresser so she can work from home and be more available for her daughter.

"I worry every day,” Uribe said. “I worry that nobody's going to be there in time to help her.”

Such medical emergencies rare, according to data from the Utah Department of Health's student injury reporting system, which tracks school-related injuries that cost at least a half-day of school or require medical attention from a school nurse, physician or other health care provider.

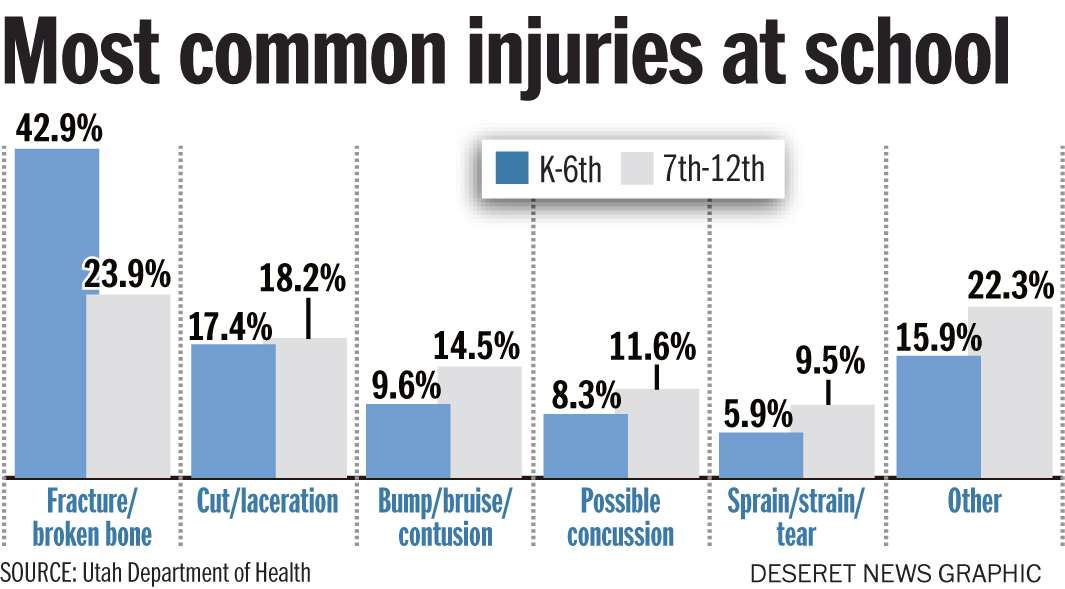

Between 2012 and 2015, Utah public schools reported nearly 13,900 student injuries that fit that description.

Potential fractures, broken bones, cuts, bumps and bruises made up the vast majority of injuries. Just 68 of those incidents were related to seizures, asthma or diabetes.

Still, school nurses say they would like to spend less time training and retraining teachers to respond to medical emergencies so they can focus on their own work.

“Honestly, we’d probably like to do all of that ourselves,” Yaworsky said. “We would much rather do it ourselves than delegate medication.”

* * *

Bodily said the problem isn’t recruiting or attracting school nurses to Utah — it’s funding them.

Funding for school nurses comes mostly from the local school districts and state educational funds. Some local health departments also help fund school nurses.

Since 2007, state lawmakers have also allocated between $882,000 and $1 million per year in matching funds for school nurses.

But that’s “not nearly enough," said Hinkson, who estimates it will cost an additional $91.1 million to place a full-time nurse in every school in Utah.

A study conducted by researchers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published in the journal Pediatrics in 2014 found that every dollar spent hiring full-time school nurses saves the public $2.20 in medical care costs, parents’ productivity loss and teachers’ productivity loss.

Studies have also shown that hiring full-time school nurses can improve attendance rates, chronic disease management and immunization rates.

Cescilee Rall, the lead nurse for secondary schools at Granite School District, said school nursing has changed “just like education has changed.”

School nurses at Granite — one of the state's largest and most diverse districts — cover six or seven junior high or high schools each, or about 4,500 students per nurse, according to Rall.

And yet "the needs of the students are greater at this point," Rall said. “Mental health needs in secondary school are very great. The number of chronically ill kids we see now is greater than I’ve ever seen before.”

That means school nurses are often on the front lines when it comes to alerting staff about students dealing with mental health issues, providing primary care for low-income students, and directing parents to medical and social resources.

In Salt Lake City School District, where nurses cover about 4,700 students each, "just a couple more nurses” would make a huge difference, Yaworsky said.

She scarcely dares to dream about what she could accomplish if the district hired a nurse for each school.

“For the most part, we handle our school situations very well,” Yaworsky said. “But there’s always that worry on our mind.

“Five nurses,” she added, “can only do so much.” Email: dchen@deseretnews.com Twitter: DaphneChen_