Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

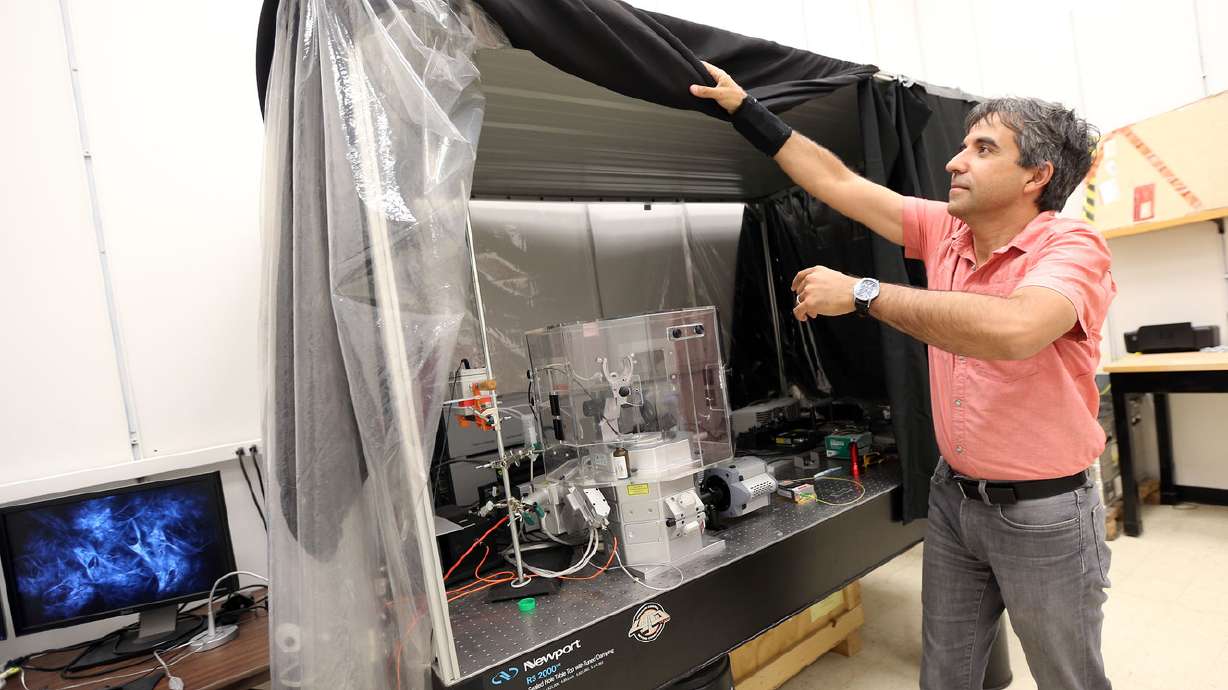

SALT LAKE CITY — Under Saveez Saffarian’s digital microscope, the viruses are tiny pinpricks of light, dwarfed by their human host cell.

But the University of Utah virologist knows that though they look benign, HIV particles take only five minutes to release from an infected cell and begin spreading throughout the body.

Scientists have made significant advances in treating HIV. But they are still working to better control the virus, its side effects and its rapidly evolving immunity to modern drugs.

Now two University of Utah researchers are finding a way to use the virus’ speed in their favor — an entirely unique approach to treating HIV.

“What we realized is there must be a race for the virus to get out,” said Saffarian, who is an associate professor of physics and astronomy at the U. He and Mourad Bendjennat, a research assistant professor of physics and astronomy, were watching HIV particles bud from their host cells when they realized that the viruses have a weakness.

If the HIV does not escape from the host cell fast enough, an enzyme called protease gets activated and starts “chewing” the proteins inside the virus, Saffarian said. By the time the viruses separate from the host cell, it has become noninfectious.

That was their "aha" moment. “If the virus is in such a rush, that means it's vulnerable,” Saffarian said.

Their research approach has implications for a unique treatment for HIV/AIDS as well as other retroviruses — a family of viruses that use a host cell to replicate.

Modern drug "cocktails" have been hugely successful at turning HIV from a death sentence into a largely manageable chronic disease.

But such drugs are not perfect: They have a unique list of side effects, still suppress the patient’s immune system and must be taken on a strict regimen.

“They have secondary effects that hurt patients,” Bendjennat said. “And the virus becomes resistant to the inhibitors. That’s why they use cocktails.”

Saffarian and Bendjennat hope to delay HIV particles from budding from their host cell long enough for its own enzymes to start destroying the virus.

To do so, they are interfering with the way HIV particles interact with a class of proteins called ESCRTs, which are crucial for helping budding HIV particles pinch off of the host cell and get into the body.

Saffarian and Bendjennat created HIV particles that interact abnormally to the ESCRTs proteins, then put them under a digital microscope and watched them try to split from the cell.

One type of mutation caused the particle's release to be delayed by 75 minutes and resulted in half the new particles becoming noninfectious.

Another delayed release by 10 hours. None of the new particles were infectious.

Their study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, was published Thursday by "PLOS Pathogens."

Some researchers are already looking at drugs that block ESCRT proteins entirely to prevent HIV particles from pinching off, according to Bendjennat. But ESCRTs are critical for many crucial functions, like cell division, so those drugs are likely to be toxic.

Instead, Bendjennat and Saffarian are looking to test low-potency drugs that merely delay ESCRTs from releasing HIV, instead of blocking ESCRTs entirely.

Bendjennat and Saffarian emphasize that their research is in the beginning stages and that it will be 10 years or more until this approach might lead to a new treatment.

"This is much more fundamental in a way," Saffarian said. "What is the playground in which these viruses are evolving? What mechanisms are they using? Understanding those basic mechanisms gives you tools that you can use for maybe HIV, maybe the next virus."

"We'd like to push it as close as we can to where somebody's going to pick it up and make it an available drug," he added.

Competitors in Germany and New York have picked up on their line of questioning and are pursuing similar ideas. That means Saffarian and Bendjennat are in a race of their own.

"Pieces of this study have been scattered around the literature for the past 15 years,” Saffarian said. “Our study just kind of connected the dots.”

Email: dchen@deseretnews.com Twitter: DaphneChen_