Estimated read time: 7-8 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

Editor's Note: This article is part of the Utah Inventions series, which features all kinds of inventors and inventions with Utah ties. Tips for future articles can be sent to ncrofts@ksl.com. SALT LAKE CITY — Have sharp finger nails? You can make them extra smooth with that nail file thanks to Howard Tracy Hall. Have a cavity? The dentist has the right tools for that, thanks to Hall. And you know that smartphone you use every day? Its screen is smooth and shiny thanks to, you guessed it, Hall. Oh, and we can't fail to mention the saw blades used in construction.

It seems like we wouldn't be where we are today without Hall. But who was he?

Hall was an Ogden native who helped discover the first reliable synthetic diamond-making process — something people had been trying to do for centuries.

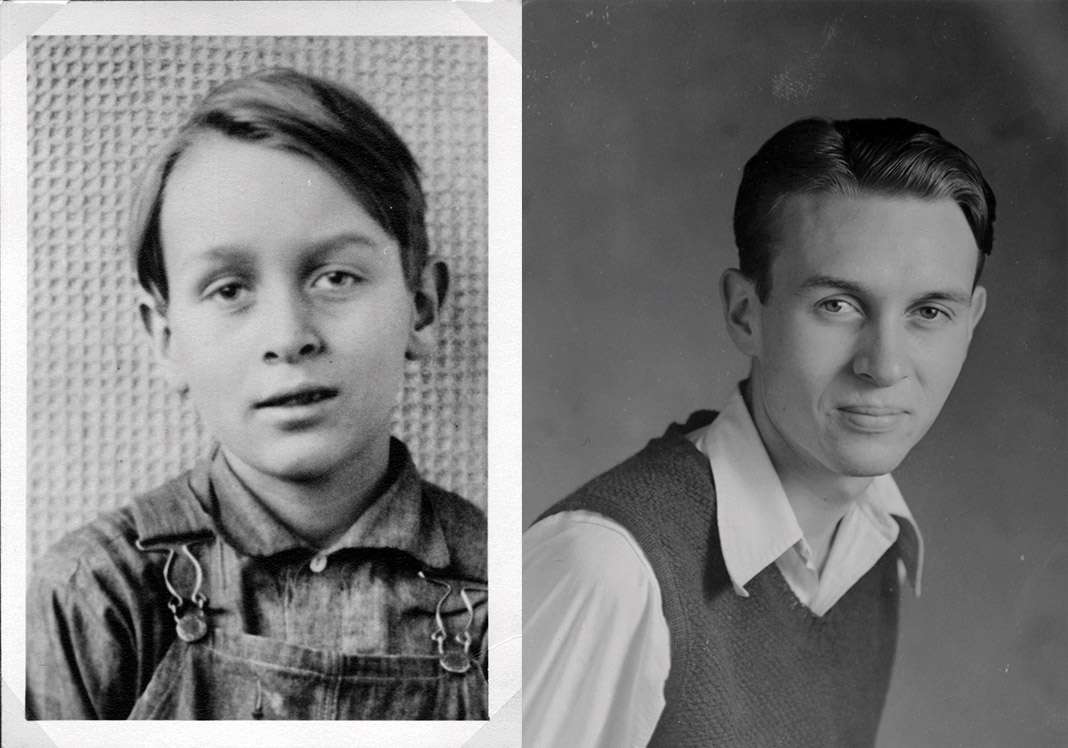

Hall came into this world on Oct. 20, 1919. Later on, his family would move to a farm in Marriott. Unfortunately, this farm would be lost during the Great Depression, when Hall was 14. These hard financial struggles probably greatly contributed to his character and success.

As a kid, he enjoyed taking things apart to see how they worked. He even experimented with fireworks, making his own cannon. His other creations included electric motors, microphones, crystal radios and telephones. Willing to support him, his mother let him tinker with her sewing machine. As quoted in "Howard Tracy Hall," a book published by Legacy Books, he recalled, "Mom prized her precious sewing machine, yet allowed [me] to take it apart and put it back together to find out how it worked."

One machine he and his brothers thoroughly enjoyed was his grandmother's Edison phonograph. Hall looked up to Thomas A. Edison and would study him at the Carnegie Public Library in Ogden. From then on, he knew he wanted to work for General Electric. In fact, he remembers, "While I was in the fourth grade in the Marriott School, our teacher asked each member of the class what they wanted to do when they grew up. I told her that I wanted to be a scientist at the General Electric Company."

Perhaps this dream wasn't too far-fetched for a fourth-grader. When he took a test that same school year, he performed better than even any of the 12-graders, according to the book "Howard Tracy Hall."

Indeed, his dream was fulfilled after beginning his education at Weber State University and the University of Utah, marrying Ida-Rose Langford in 1941, joining the Navy in 1944 and receiving a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Utah in 1948. He said, "My boyhood hero, Thomas Edison, had his first machine shop on the banks of the Mohawk River, and now I was working in that very area!"

GE was working on Project Super Pressure, the goal of which was to create synthetic diamonds. The seeds of this project began during WWII, when diamond use went up exponentially due to weapon manufacturing. After the war, people realized diamonds could be used in daily manufacturing, such as for making cars. So GE decided to continue trying a feat that for many was fruitless. In fact, originally no one volunteered to work on this project except Hall.

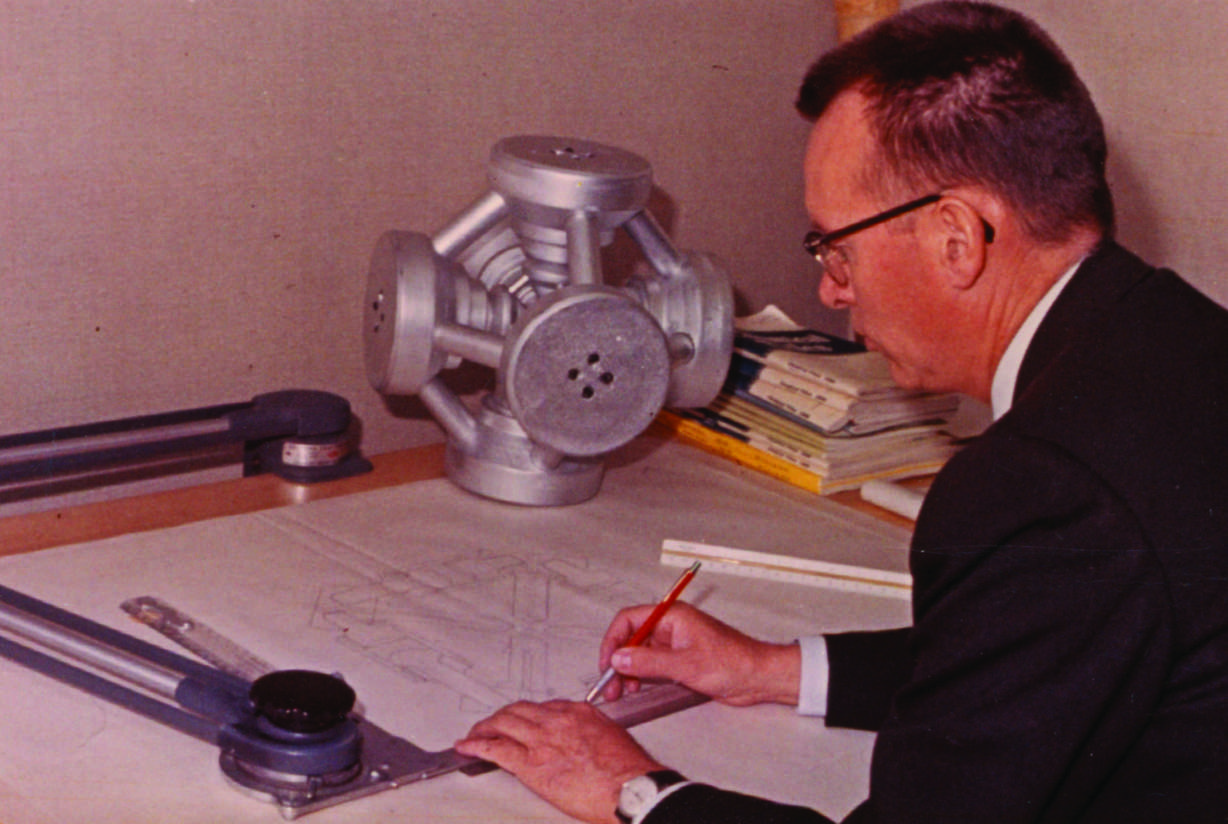

Hall and the project team spent their lunches discussing and theorizing how to transform graphite, the kind of carbon found in pencil lead, into diamonds. They worked hard experimenting with apparatuses. Meanwhile, Hall was working on his first invention: the belt apparatus.

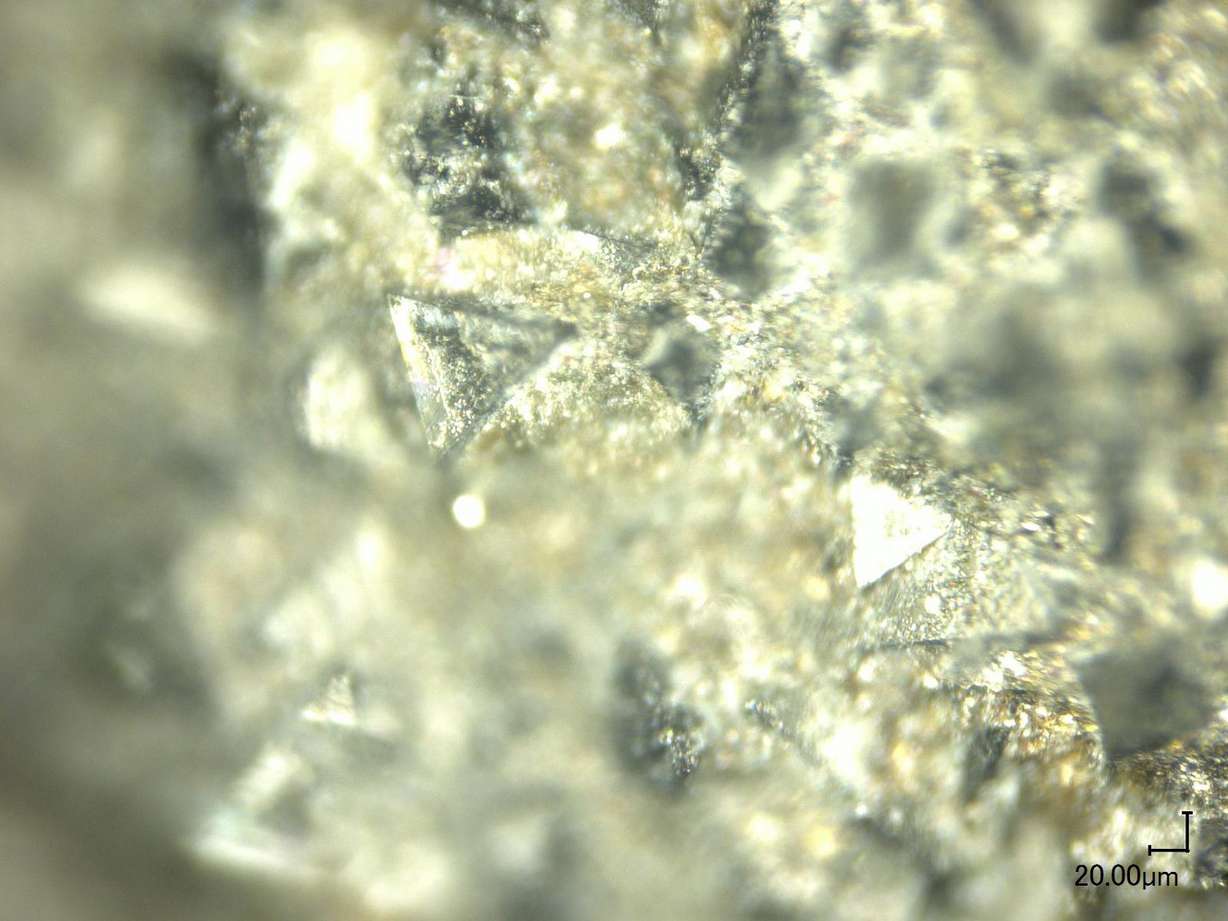

Then on Dec. 16, 1954, Hall was working alone in the lab. When he looked in his belt apparatus, there were diamonds! According to "The Washington Post," Hall wrote of this experience, "My hands began to tremble; my heart beat rapidly; my knees weakened and no longer gave support. My eyes had caught the flashing light from dozens of tiny... crystals. And I knew that diamonds had finally been made by man."

As the experiment was repeated, it kept working.

This was a huge breakthrough. While other people (like Erik G. Lundblad of ASEA in Sweden and William G. Eversole of Union Carbide in New York) had successfully created diamonds, their processes were slow, not always successful and had been kept quiet. It wasn't until Hall's innovation that synthetic-diamond making really took off and found success.

And what's really amazing is no natural diamond was needed to set off the process! The innovation was announced in February 1955. That same year, Hall started the company Novatek.

Unfortunately, Hall did not receive nearly the credit he deserved. So later that year, he left GE for Brigham Young University to teach chemistry and serve as the director of research. However, he said of GE, "I have only good to say about the company and the people ... One of the smartest things I ever did in my life was to kind of force myself upon the General Electric Company."

While at BYU, despite the government's alleged attempts to prevent Hall from using his own invention (due to their knowledge that synthetic-diamond manufacturing was very significant), he was able to create a better machine — a tetrahedral press. This machine had four rams total, instead of just one like his original belt. The government reportedly tried to prevent him from using this machine as well, but they eventually consented to his free access of it.

Two other BYU professors, M. Duane Horton and Bill J. Pope, convinced Hall to start a company making diamonds for industrial use. In 1966, Mega Pressure Products and Research Corporation was born. However, they changed its name to MegaDiamond when, in 1968, Hall's cubic press— which had six rams and anvils and so could work more quickly — created carbonado, a polycrystalline diamond. When someone asked him to prove that this black crystal was actually a diamond, he scratched their living room window! In honor of this feat, the company name was changed to MegaDiamond.

Hall did not receive nearly enough recognition for what he did. John Catron, a family and personal biographer at Riverton-based Legacy Books, said, "The impact of Dr. Hall's inventions are immeasurable. It was incredible to just invent the first apparatus and system that could synthesize diamonds repeatedly."

He emphasized, "There is nary an industry that at some point does not utilize synthetic diamond in its production. He's the perfect example of dreaming big and obtaining an education equal to your dreams."

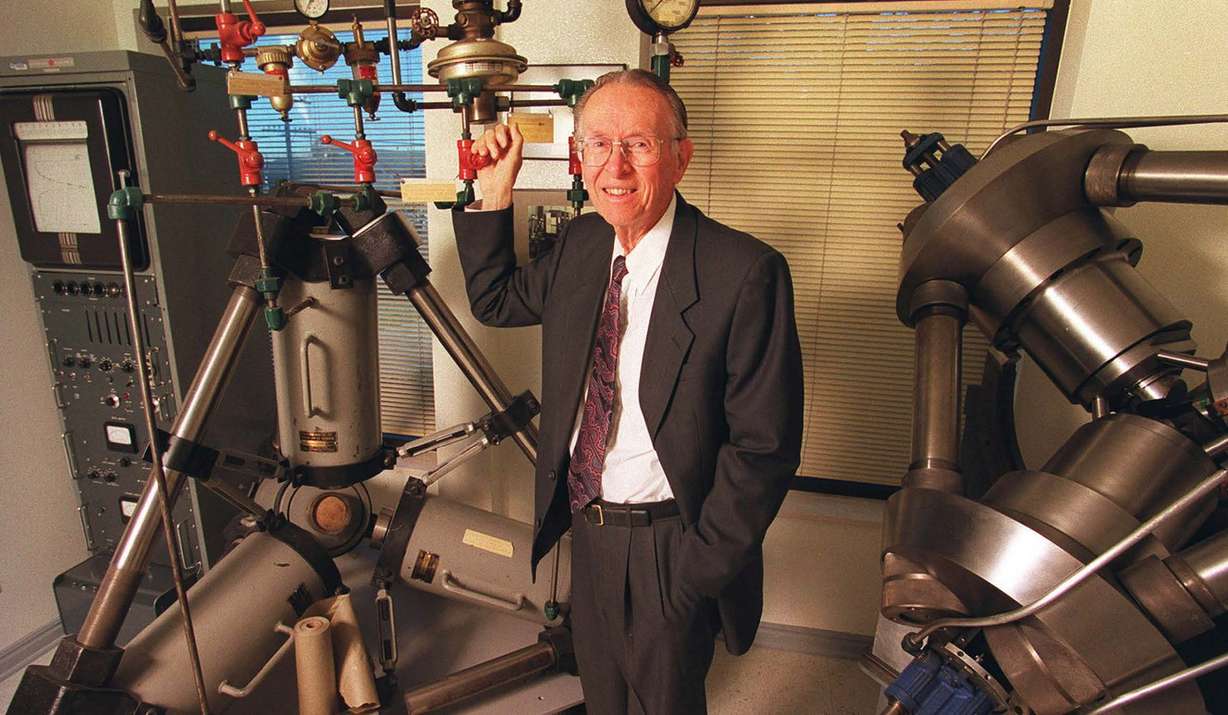

While he did not receive quite what he deserved for his influence, Hall thankfully did receive recognition. In 1977, Hall was honored by the American Physical Society, and in 2004 he was granted an Honorary Doctorate of Science from University of Utah, for example.

And in the fall of 2016, Weber State University's Tracy Hall Science Center will be completed. The building was named in Hall's honor.

Believe it or not, Hall had a life besides diamonds. He was truly dedicated to his family and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He also worked as a tree farmer in Payson. He bought the farm in 1968, the year after resigning as BYU's director of research, and eventually began growing and selling trees.

He said of this experience, "Financially, this project is a flop. Does it have other rewards? Quite probably. It is challenging, and it gives me lots of exercise. Also, turning over the soil to expose fresh, new earth made me think of turning points. What if your life or my life took this turn or instead took that turn? What would the result have been?"

With all his success, Hall made sure to put credit where he felt credit was due. He stated, "All that I have accomplished in life I can attribute to remaining close to the church and keeping the covenants that I made with my Father in Heaven."

Hall died July 25, 2008.

Related Story

Katrina Lynn Corbridge Hawkins is a graduate of Brigham Young University, a Utah native, and a freelance writer. You can contact her at katrina.hawkins21@gmail.com.