Estimated read time: 3-4 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY -- Journalists love the term and physicists hate it, but no one doubts the importance of discovering the Higgs boson, better known as the God particle.

It's been 50 years and tens of billions of dollars in the making, but Thursday the physics world erupted with excitement, anticipation and not a little speculation as scientists at Europe's physics juggernaut CERN hinted that they had signs of the Higgs boson.

On Dec. 13, researchers will release data indicating what could be the first glimpses of the particle. The results are not certain, but they appear to be promising. Still, despite the excitement, CERN's director general Rolf Heue was quick to point out that the will not be announcing a formal discovery next week.

Discovery has a technical definition in the world of physics: a discovery must have a certainty of 5-sigma. That means that the chances of being wrong are about the same as flipping a coin and having it come up heads 20 times in a row - less than one in a million. In other words, discoveries must have a fantastically low probability of being wrong. The results to be presented on Dec. 13 are not yet at that level of certainty, but perhaps as early as next year, CERN expects to get there.

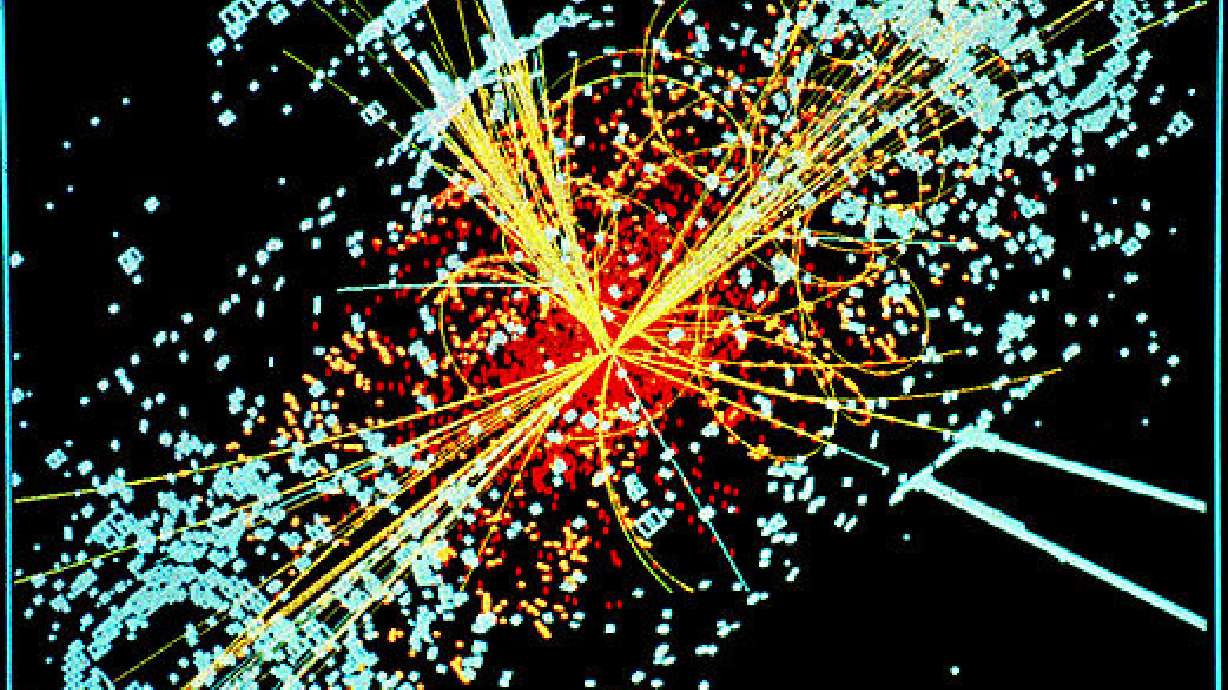

For the last year or so, CERN researchers have been dutifully smashing protons together at close to the speed of light in the hopes of getting a fleeting peek at the Higgs boson, perhaps the most important particle that has never been seen. The Higgs is the, as yet, theoretical particle which gives some particles a lot of their mass. That is to say, it is the particle responsible for why you and I weigh anything and have any substance at all.

To understand the Higgs boson, you have to think of space as a big party called the Higgs field. When a really popular guest shows up, say an electron, the lonely Higgs want to crowd around the newcomer and talk with it, because, of course electrons are good looking and interesting particles. As the electron moves around the party, the crowd goes with it, affecting its movements and its interactions with other popular guests at the party. This crowding is what endows the electron with part of its mass.

We tend to think of mass in terms of weight, like 100 pounds or 50 kilograms. At the subatomic level, though, mass is actually measured in terms of energy, specifically the electron-volt, thanks to Einstein's famous and handy equivalence, E=mc2. The Higgs boson should have a mass somewhere between 120 and 125 gigaelectron-volts, based on experiments at CERN and Fermilab in Chicago. That makes it one of the heaviest particles around - as heavy as two copper atoms. Perhaps that's why it's desperate to get the attention of the dainty electron at the party.

Discovery of the Higgs would be a serious confirmation of the already incredibly solid Standard Model of particle physics, a mathematical model that describes the behavior and properties of every known particle. The Higgs is predicted by that model, but is the last unobserved member of the set. Its discovery would cement the Standard Model as one of the best confirmed theories in science, rivaling Einstein's relativity.

Email: dnewlin@ksl.com