Estimated read time: 6-7 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

SALT LAKE CITY — Most cases on file in courthouses throughout the state can be readily retrieved with a name or number — available to anyone who wants to see them.

But dozens of special criminal investigations tucked away in a locked cabinet and logged in a spiral notebook rarely, if ever, meet the public eye.

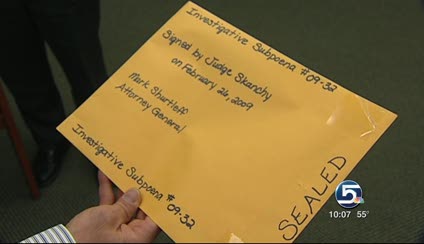

Though the files contain a mix of public and private documents detailing activities of state, county and city prosecutors, there is no way for the public to access them or even know they exist. Each one comes with a court-issued secrecy order and the court uses an off-the-grid numbering system to account for them.

Law enforcement routinely uses what are known as investigative subpoenas to root out crime much like a grand jury would. But though judges sanction the investigation, they have little oversight after their initial blessing. And there's no way to know if the records the law requires for each file are included.

Why the files are kept secret

Prosecutors say the secrecy serves to keep from tipping off bad guys or to protect witnesses. Some defense attorneys, though, say the practice leaves room for abuse by overzealous prosecutors.

"You can't just go around telling people you're investigating them. It's not very effective," said Scott Reed, criminal justice division chief in the Utah Attorney General's Office.

You can't just go around telling people you're investigating them. It's not very effective.

–Scott Reed, Utah Attorney General's Office

#reed_quote

Kent Hart, executive director of the Utah Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, doesn't dispute that there are times when secrecy is needed, but those are rare.

"Anything done in secret is going to be relying on the good faith of the prosecutor," he said. "There has to be a check somewhere on the prosecutor and police or the risk is they will run roughshod over unsuspecting people."

Utah's subpoena powers law allows the attorney general's office and county and city attorneys to question witnesses and obtain evidence such as bank or income tax records with the approval of a judge. Prosecutors must provide a statement of good cause to justify a subpoena and secrecy order.

Secrecy orders are public records, but there is no way to know the files even exist. The court uses a separate numbering system for those cases. They do not appear on public court dockets nor are they entered into the court's computer database.

In the Matheson Courthouse in Salt Lake City, cases are logged with handwritten entries in a black spiral notebook, which the court does not allow the public to view. The files are kept in a locked cabinet.

How KSL learned of the files

Lynn Packer, a former investigative reporter and BYU journalism instructor, stumbled across the secret files as the result of a business dispute with Weber State University. His complaint to the attorney general's office initiated an investigation in which subpoenas and secrecy orders were issued.

His questioning investigators about the case eventually led him to petition a 3rd District judge to open the file, which gave him a glimpse into documents that might or might not be kept there.

"They keep this so secret that there's just no trace of it in the public record," he said. "It's probably the first secret case file to be unsealed."

When KSL News requested copies of secrecy orders for the past three years filed at the Salt Lake courthouse, the district court's lawyer, Brent Johnson, reviewed each of the cases before providing the documents. Other than secrecy orders, he said, there were no other pubic documents in the 26 cases provided. Some contained multiple or expanded secrecy orders.

The secrecy orders themselves contain no information as to the nature of the investigations. Names of individuals or organizations were redacted from the documents.

"There are very detailed good cause statements in there for the judges to review. And yes, the public does not have access to those at this point," Johnson said.

The files contain various types of cases including homicides, financial fraud and sex crimes, he said. But there is no way to know how or why those investigations were conducted and whether they resulted in criminal charges.

"I guess from a public standpoint it would be difficult to review that, so all you have is my word that everything is going well," Johnson said.

Management of the files

As a result of KSL News and Deseret News questions about how the files are managed, Johnson said the state Administrative Office of the Courts intends to look at how it manages those secret files. Johnson said it will determine if the files can be put into the computer system and what kind of information can be put on the docket.

Hart finds the inability to scrutinize the cases troubling.

Experience has shown that when we're dealing with government, we don't want to trust them. We have to shine a light on it.

–Kent Hart, Utah Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers

#hart_quote

"Just because someone says it should be held secretly, do we really want to trust that person's judgment?" he said. "Experience has shown that when we're dealing with government, we don't want to trust them. We have to shine a light on it."

Reed said yes, people have to simply trust prosecutors.

"We go get judicial oversight. We just don't run willy-nilly off into the woods on some complaint over the phone anonymously. We have to show good cause," he said.

Reed estimated that about 80 percent of those investigations result in criminal charges.

Busy judges, however, have little time to track each case after they issue investigative subpoenas and secrecy orders. One sitting district court judge declined to comment on the handling of the cases, while two retired judges said they are too far removed from the bench to discuss it.

"You've got a balancing of interests here. The government needs some secrecy to conduct investigations, but on the other hand we don't want to give them a blank check to do whatever they want without any kind of oversight," said University of Utah law professor Paul Cassell. "So, the judges are tasked with reviewing applications to see if there really is a good reason for secrecy."

Because the cases are secret, there's no way to know whether investigators maintain the cases according to state law, which provides a checklist of records that should be included in the files. One of those items is a detailed description of all the documents and evidence produced from the subpoenas.

You've got a balancing of interests here. The government needs some secrecy to conduct investigations, but on the other hand we don't want to give them a blank check to do whatever they want without any kind of oversight.

–Paul Cassell, University of Utah law professor

#cassell_quote

Packer said that was missing in his case. "It was clear that no one was following the law in terms of handling these secret files," he said.

Though Reed said investigators should abide by the law, he couldn't say for sure it happens in each case.

"Investigators as a group are very eager to go out and investigate," he said. "They are less eager to engage in the more mundane tasks of file management and paperwork."

But, Reed said, all the required records should be in a file when the investigation is done.

"I don't think it's so much a question of keeping things secret permanently, but more a question of keeping something secret temporarily while the investigation is moving forward in sensitive phases," said Cassell, a former federal judge and prosecutor.

Reed said he has no problem with files being opened after an investigation is complete regardless of whether charges are filed. But they should stay closed while investigators are at work.

"We're cognizant of the public's right to know," he said. "We're a little less receptive to the notion of the public's right to know right now."

Of course, the public would have to know that such documents exist. Under the current system, there is no way to find out.

-----

Written by Dennis Romboy with contributions from John Daley.