Estimated read time: 4-5 minutes

This archived news story is available only for your personal, non-commercial use. Information in the story may be outdated or superseded by additional information. Reading or replaying the story in its archived form does not constitute a republication of the story.

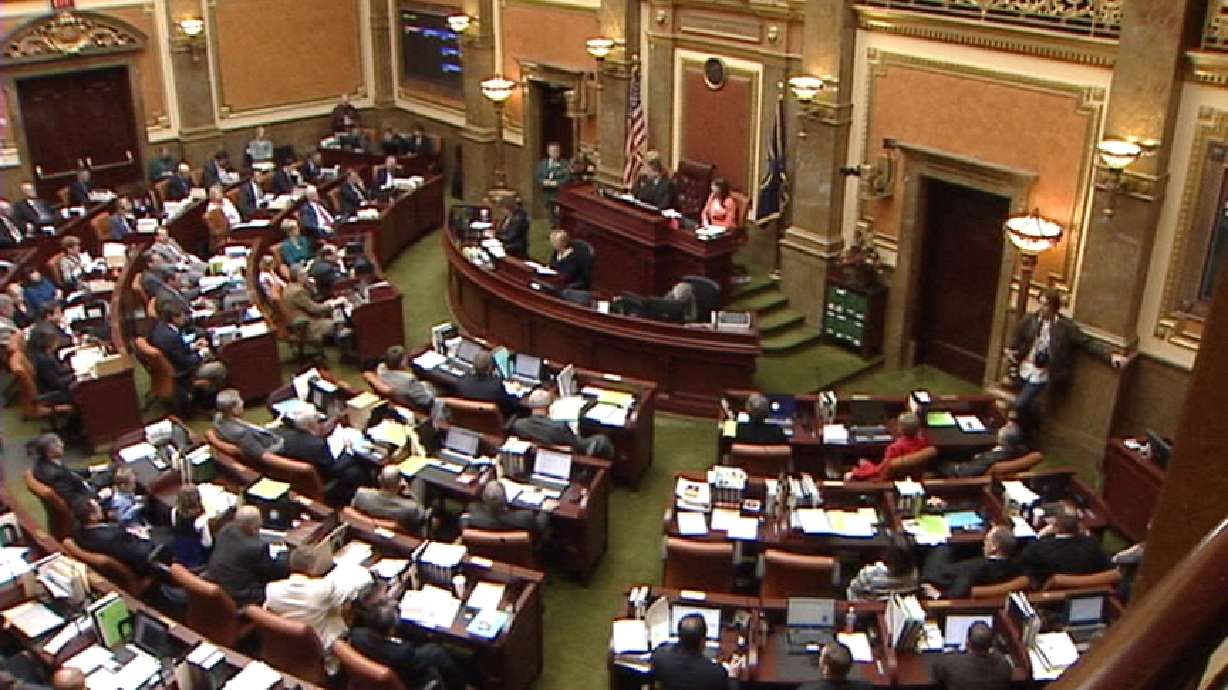

SALT LAKE CITY -- Given the traditional tension between elected officials in the Utah Legislature and members of the news media who cover them, the last-minute effort to eviscerate the state's public records laws should not come as a big surprise.

What is a surprise is the degree to which the proposal appears more to be the sour fruit of pent-up frustration than any sound policy analysis.

"It almost seems as if they have been storing up their concerns and see this as an opportunity to let them all out at once," said Jeffrey J. Hunt, a lawyer for the Utah Media Coalition who was among the original architects of the Government Records and Management Act (GRAMA).

As a result, what threatens to get lost in the debate is the fact that legitimate, real-world questions do exist over whether the law properly addresses changing communications technology, and whether there are adequate controls to mitigate the demands the law puts on those who create and keep public records.

Related:

The question the public should be concerned with is whether HB477 is exposing these problems in order to fix them, or rather to use them as a bludgeon to punish the press for what some lawmakers see as wanton attempts to use public records laws to embarrass politicians.

The bill contains several specific changes to existing laws which would have far-reaching consequences. It would establish that all text messages, instant messages, recorded video chats, and voicemails are private, regardless of their content. It eliminates the language that describes the legislature's original intent in creating the 1991 law, which has been interpreted by the courts as a statement in support of considering the status of most records to be public first, private second. It also grants government agencies the ability to set fees to process a records request which could become substantial, if not prohibitive, or even punitive.

And clearly, for some legislators, it is as much about personal business as public business.

"We're getting to the point where we want to mic up and put a camera on a legislator to monitor everything he does and everything he or she says not just when they are involved with the legislative process, but in his or her life," says the bill's sponsor, Rep. John Dougall, R-Highland.

The notion that lawmakers could someday find themselves in a "Truman Show" world of 24-hour media surveillance is bizarre, but not necessarily without some basis of legitimate concern.

New technology has indeed changed the way communications is conducted and information disseminated. Rep. Mike Noel, R-Kanab, chairman of the committee that voted unanimously to pass the bill to the House floor, talked about how teenagers will text each other while actually within range of a verbal conversation.

Under GRAMA, the nature of the verbal conversation is private, but the text message version would constitute a record that could be public.

The operative word there is "could." The GRAMA law has numerous provisions that allow for a sharp distinction between what constitutes public and private information. A key principle of GRAMA, according to Mr. Hunt, is its "balancing mechanism" which serves to preserve the public's right to oversee government actions, and individual privacy.

What constitutes a private versus public record is a test that can be applied equally to documents tapped out on a Blackberry or scratched out with ink and quill.

Another frustration that permeates the debate comes from the perception that news reporters wield the GRAMA laws to embark on "witch hunts" in search of communications that would place legislators in embarrassing light. Supporters of the bill complain that legislative staff is often burdened with excessive requests for "any and all emails" on certain subjects or between certain parties, often on matters that have already generated controversy. A recent request for records relating to the debate on a bill that would allow people to shoot feral cats is said to be among the examples of what those in favor of the law say demonstrate media abuse of GRAMA.

Journalists may promise their interest is to chronicle the work of government and not seek or exploit embarrassing information they may encounter along the way. Legislators may promise that if all text messaging is made private, they won't start using text messaging to communicate on all sensitive issues.

We may or may not choose to believe both, or neither.

But as legislative adjournment draws near, we are left with the very real prospect of a sharp and hasty reversal of course by a body of lawmakers that has traditionally championed open government and over the years, nurtured an open records law that has been praised nationally as a beacon for the public's right to know.

"This body has a strong record of acting as a champion of open government," Mr. Hunt says. It is a record that would abruptly end with the passage of HB477, a bill that may have been born with the best of intentions, but if passed into law, will leave the concept of transparent government very much subordinate to the law of unintended consequences.

E-mail: cpsarras@ksl.com